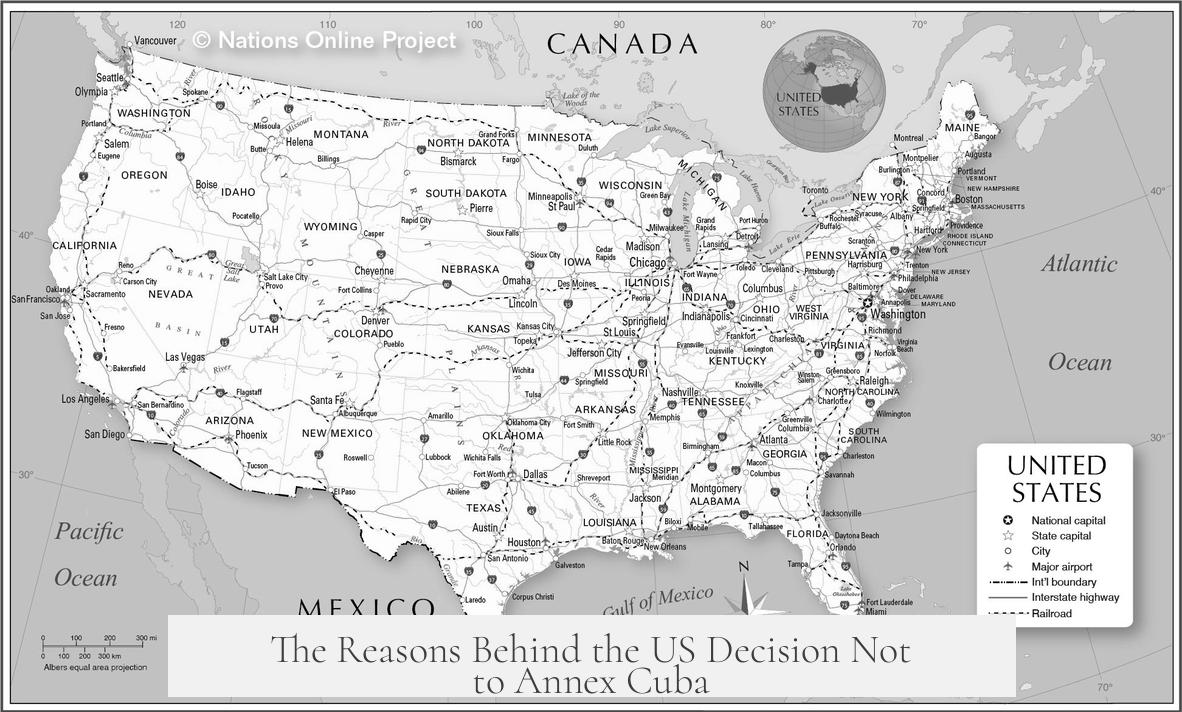

The United States did not annex Cuba due to longstanding political, racial, and ideological divisions regarding expansion in the Caribbean region. These divisions stem from complex historical debates that occurred over the 19th century and shaped U.S. foreign policy attitudes toward Caribbean territories.

In the early to mid-1800s, before the Civil War, pro-slavery factions in the U.S. aggressively supported territorial expansion in the Caribbean. These groups viewed annexation as a way to protect and extend slavery. For example, pro-slavery Congressman Thomas Clingman advocated for annexing the West Indies to reinstate slave labor after Britain emancipated slaves in its Caribbean colonies. Some private incursions into Central American republics even aimed to halt abolitionist movements.

After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, Republican politicians championed expansion as a symbol of renewed American nationalism. This period saw the purchase of Alaska and increasing interest in Caribbean territories. Yet, tensions persisted over the region’s racial and political characteristics. The Caribbean was viewed as a crucial but sensitive zone for U.S. ambitions.

The 1870 annexation treaty with the Dominican Republic exemplified these complexities. The Grant administration pushed the treaty to secure a naval base to deter European colonial ventures and to economically uplift the Dominican Republic using the free labor ideology favored by abolitionists. Influential figures like Frederick Douglass supported this plan, seeing it as a moral alternative to slavery and a path to influence nearby slave societies like Cuba and Puerto Rico toward abolition.

Despite these intentions, the treaty failed. Opposition came from an unusual coalition. Senator Charles Sumner, a staunch abolitionist, argued annexation risked embroiling the U.S. in local conflicts and threatening Haitian sovereignty. Sumner’s stance reflected his consistent opposition to Caribbean expansionist agendas previously promoted by pro-slavery advocates.

At the same time, racist lawmakers opposed annexation by arguing that Caribbean populations, largely non-white, were unsuitable for American citizenship and feared “degenerate races” entering the Union. This collision of anti-expansionist abolitionists and racists created a potent ideological force against imperialism in the region.

This coalition birthed what historians call “racial anti-imperialism.” It expressed moral concerns about power and sovereignty alongside racial anxieties about extending U.S. citizenship to non-white peoples. These arguments strongly influenced American resistance to annexing Cuba after the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Although some Americans supported Cuban independence outright, the dominant political climate, shaped by earlier debates and racial anxieties, blocked formal annexation. The U.S. government instead established a protectorate, overseeing Cuba’s affairs without outright incorporation into the Union. This strategy balanced strategic interest with domestic political realities.

| Factor | Impact on Cuba Annexation |

|---|---|

| Pro-slavery expansionism (pre-Civil War) | Initial push for Caribbean annexation to protect slavery and labor interests |

| Post-Civil War Republican nationalism | Support for expansion as a display of free labor and American values, but with caution in Caribbean |

| 1870 Dominican Republic treaty’s rejection | Highlighted divided opinions over sovereignty, racial inclusion, and potential conflict |

| Coalition of abolitionists and racists | Unified to oppose expansion to Caribbean due to concerns over race and political stability |

| Emergence of racial anti-imperialism | Set precedent that limited U.S. imperial ambitions in Caribbean post Spanish-American War |

The failure to annex Cuba reflects intertwined issues of race, sovereignty, and national identity. It illustrates how historical debates about slavery, citizenship, and American expansionism shaped U.S. foreign policy decisions. While Cuba remained under U.S. influence, annexation would have crossed political boundaries that domestic coalitions refused to breach.

- The U.S. Caribbean expansion debates originated from slavery interests and abolitionist nationalism.

- 1870 Dominican Republic annexation was blocked by abolitionists and racists for distinct reasons.

- This coalition created racial anti-imperialism, preventing annexation of Cuba after 1898.

- Concerns included civil conflict risk, sovereignty, racial citizenship, and political stability.

- The U.S. chose indirect control of Cuba over formal annexation to navigate these tensions.

Why Didn’t The US Annex Cuba?

The United States didn’t annex Cuba after the Spanish-American War because of deeply rooted political and racial tensions that had evolved over decades. These tensions created a complex brew of interests, fears, and ideologies that ultimately prevented Cuba’s incorporation into the U.S. Instead of annexation, the U.S. opted for a more indirect control, which shaped Cuba’s unique path in the 20th century.

But to understand why the U.S. passed on annexing Cuba, we need to rewind a bit – way before the battleship Maine blew up in Havana’s harbor.

Early Ambitions and the Caribbean Chessboard

During the 19th century, U.S. territorial expansion wasn’t a spontaneous idea cooked up in the aftermath of one war. Rather, it was a hot topic in political debates spanning decades. The Caribbean, with its strategic islands and valuable ports, was a prized piece on this chessboard.

Before the American Civil War, southern politicians who backed slavery eyed the Caribbean hungerily. For them, annexing islands like Cuba meant more than just land – it was about saving their slave-based economy from the wave of abolition sweeping the Atlantic world.

Take Congressman Thomas Clingman, for example. This fiery pro-slavery advocate openly called for annexing the West Indies to bring back slavery. To him, re-enslaving Black populations on these islands was not just practical, it was essential.

But it wasn’t just talk. Some pro-slavery groups even organized private invasions into Central American republics. They tried to freeze out abolitionist movements and guarantee slavery’s survival. If that sounds intense, it’s because it was.

The Civil War’s Aftermath: A Shift in Expansionist Dreams

After the Union’s victory ended slavery, the vision changed. A new breed of politicians, mostly abolitionist Republicans, took center stage. These folks saw expansion as a way to promote American nationalism and extend the ideals of free labor.

Alaska’s acquisition from Russia shows this new expansionist phase. However, the Caribbean remained tricky. Unlike Alaska, where indigenous peoples were far from American eyes and politics, Caribbean islands held histories of slavery and racial difference that made expansion unusually sensitive.

The Dominican Republic Annexation Treaty: A Preview of the Cuban Debate

In 1870, the U.S. almost annexed another Caribbean nation: the Dominican Republic. The Grant administration aimed for a naval base to block European meddling, especially after recent French adventures in Mexico had stirred anxiety.

Reformers like Frederick Douglass supported annexation of the Dominican Republic, seeing it as a chance to uplift the island through free labor systems, showing that economic freedom beat slavery. They hoped this would pressure neighboring Cuba and Puerto Rico toward abolition.

But the treaty failed in Congress. Why? Because a surprising coalition rose up against it.

Racial Anti-Imperialism and Political Resistance

Senator Charles Sumner, an abolitionist, objected because annexing the Dominican Republic risked pulling the U.S. into local conflicts and threatened nearby Haiti’s sovereignty. His stance evolved from years of opposing southern pro-slavery expansionism.

What’s fascinating is that Sumner was joined by opposition coming from a seemingly opposite source – racists in Congress. They feared annexing islands with non-white populations. They worried America would “absorb degenerate races.”

This strange alliance helped birth a form of “racial anti-imperialism”—a political stance that rejected expansion into territories inhabited by people deemed racially unfit for citizenship. This coalition held strong sway against annexing Cuba later on.

The Cuban Avoided Fate

So when the Spanish-American War ended in 1898, the U.S. faced the question: annex Cuba or not? Thanks to these entrenched ideologies and political anxieties, the answer leaned decisively against annexation.

The U.S. didn’t want to absorb a large non-white population with a strong desire for independence. It also didn’t want to deal with the civil unrest threatening these Caribbean lands or challenge neighboring sovereignties – a lesson learned from the Dominican Republic attempt.

Cuba instead became a U.S. protectorate under the Platt Amendment, which allowed significant American influence without formal annexation. This setup gave the U.S. control over Cuban foreign policy and military bases, but kept a veneer of Cuban sovereignty.

What Can We Learn From This History?

This episode shows how American expansion was not just about land or power, but also about race, identity, and national self-definition. Before the Spanish-American War, expansion was tied up with slavery and its abolition. After the Civil War, it entangled with racial fears and political calculations.

In a way, the U.S. dodged a bullet by not annexing Cuba. The island’s struggles with sovereignty, independence, and U.S. influence played out very differently than if Cuba had become just another state or territory.

Understanding these layers helps explain why the U.S. made the choice it did. Territorial ambition wasn’t the whole story. Instead, ideas about race, citizenship, and stability shaped one of the pivotal moments in Caribbean-American relations.

In Closing

The refusal to annex Cuba was no accident. It was the result of a long history of debate, from pro-slavery expansionism to abolitionist nationalism to racial anti-imperialism. This complex history influenced U.S. policy decisions and continues to inform the legacy of America’s relationship with Cuba today.

“The American empire’s edges have always been shaped by more than maps—they reflect battles over identity, race, and power that continue to echo.”

Want to dive deeper? Check out Eric Foner’s Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 or Matt Karp’s This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy for eye-opening perspectives.

Why was U.S. territorial expansion in the Caribbean contentious before annexing Cuba?

Before annexing Cuba, the U.S. faced deep divisions over Caribbean expansion. Pro-slavery factions aimed to protect slavery by annexing territories, while abolitionists opposed such moves, fearing conflicts and racial issues.

How did the 1870 Dominican Republic annexation treaty influence U.S. policy on Cuba?

The treaty’s rejection revealed fears of involving the U.S. in island conflicts and concerns over racial integration. This opposition shaped broader hesitation toward annexing nearby territories, including Cuba.

What role did racial attitudes play in stopping the annexation of Cuba?

Racial anti-imperialism emerged from concerns that incorporating Caribbean populations would bring non-white groups into the U.S. Some lawmakers opposed annexation fearing racial mixing and citizenship issues.

Why did abolitionists both support and oppose Caribbean annexations?

Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass supported annexations to promote free labor over slavery. Yet others feared entanglement in conflicts and the impact on neighboring nations, leading to a split in their stance.

Did economic or military interests push for annexing Cuba after the Spanish-American War?

While strategic interests like naval bases were considered, political and racial opposition outpaced these concerns, preventing annexation despite military victories.