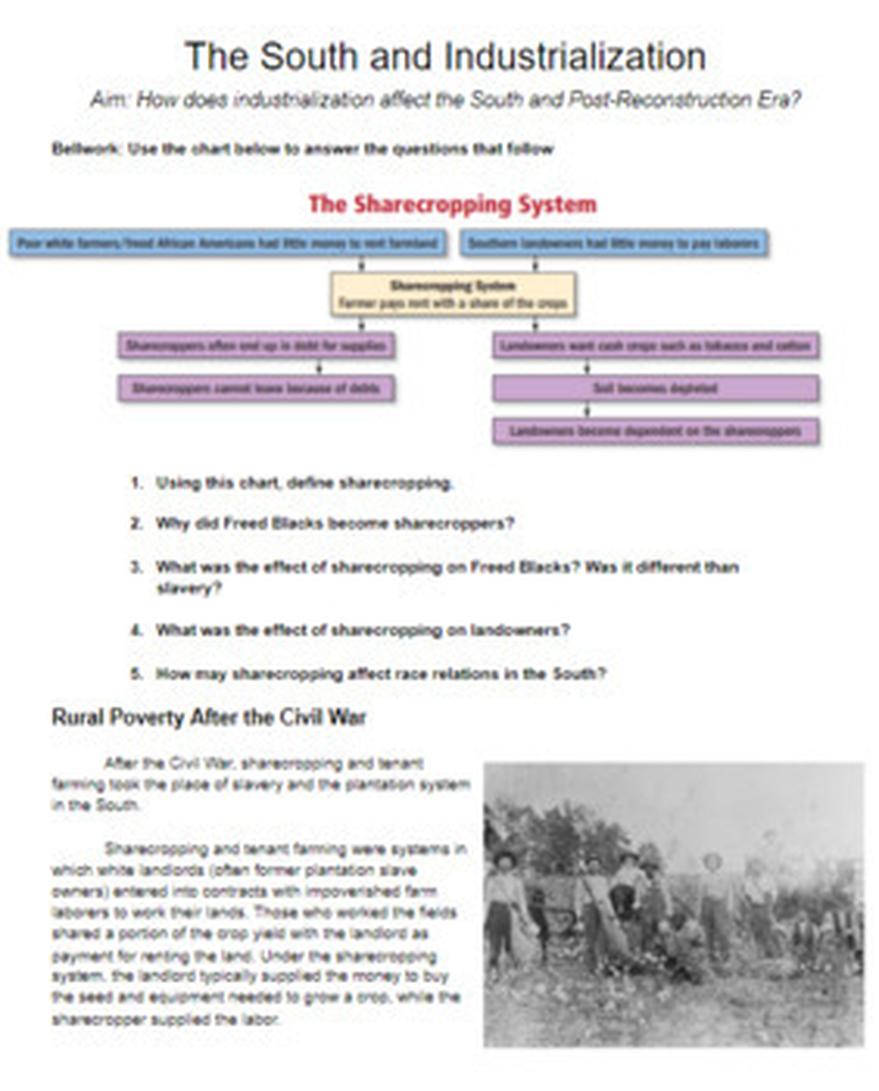

The South did not industrialize before the American Civil War due to a mix of environmental, economic, labor, social, and cultural factors that favored agriculture over manufacturing. The region’s climate, labor system, and economic incentives created obstacles to industrial growth.

Southern heat made indoor work difficult. Textile production, a leading industry, required controlled indoor environments. Before air conditioning, the intense Southern heat made factory labor dangerous and inefficient. This climate factor discouraged investments in factories.

Geography also played a role. Northern states benefited from fast rivers that powered mills cheaply and had good ports for exporting goods. In contrast, Southern geography favored large plantations. The soil suited cash crops like cotton rather than diverse agriculture or industry. These geographic advantages shaped economic focus toward agriculture.

The local market in the South was less developed. Southern consumers were generally poorer than Northern ones. This limited demand for industrial goods within the South. Without a strong regional market, industrial ventures faced weaker sales prospects and lower profits.

Planters held vast tracts of land devoted to cotton cultivation. Cotton exports brought significant wealth, paid well by Britain’s textile industry. Investing in untested industrial ventures appeared risky and less profitable than expanding cotton production. This economic logic created a strong incentive to maintain agriculture over trying manufacturing.

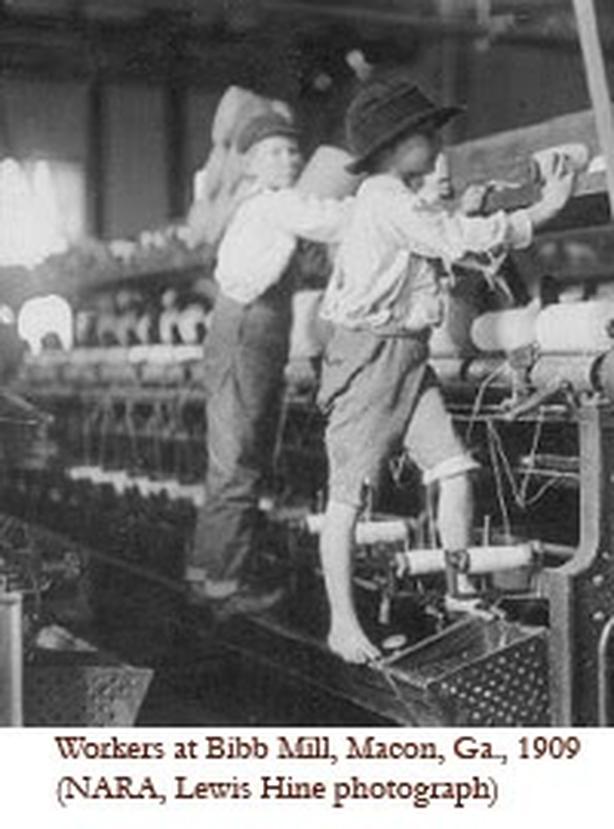

Labor systems deeply influenced Southern economics. The region’s economy relied on enslaved African Americans who worked plantations. These slaves required housing and food regardless of productivity. Industrial work demanded skilled labor and the flexibility to fire underperforming workers, which suited immigrant labor in the North but not slavery.

Slave labor was expensive and inflexible for factory use. A factory owner needed steady reinvestment and the ability to adjust labor swiftly. The enslaved labor system constrained such business dynamics. This mismatch made slavery incompatible with industrial labor needs.

Southern planters heavily invested wealth in slavery-based agriculture. They were conservative investors, reluctant to risk assets on manufacturing’s high upfront costs. This conservative stance slowed industrial emergence.

Immigration patterns differed sharply. The North attracted many European immigrants who supplied needed factory labor and encouraged urban growth. In contrast, fewer immigrants settled in the South, partly due to slavery’s social stigma. The South’s lower population density and labor shortages further impeded industrialization.

Cultural explanations that Southerners disliked machines lack strong evidence. Rather, economic and labor realities drove choices. Entrepreneurs in the North embraced risk and innovation. The South had fewer incentives to take industrial risks while agricultural profits remained secure.

Additionally, Northern textile industries benefited from cheap Southern cotton. This economic interdependence encouraged Northern interests to maintain the South’s agricultural focus and avoid Southern industrial competition.

Despite this, the South was not entirely without industry. Cities like Charleston and Atlanta had manufacturing facilities including arms production. Railroads existed, mainly connecting ports to markets in the North. However, the scale of industrial infrastructure was much smaller compared to the North’s extensive network supporting factories.

| Factor | Impact on Southern Industrialization |

|---|---|

| Climate | Hot weather hindered indoor factory work. |

| Geography | Favorable to plantations; rivers and ports less suited for northern-style mills. |

| Labor System | Slave labor incompatible with skilled, flexible factory employment. |

| Economic Incentives | Cotton exports more profitable than uncertain industry. |

| Market Demand | Weaker local consumer base limited industrial goods sales. |

| Immigration | Fewer immigrants meant less labor supply for factories. |

| Risk Culture | Planters avoided risky industrial investments. |

| Northern Interests | North preferred South’s agricultural status for cheap cotton supply. |

- The Southern climate and geography favored agriculture over industry.

- Slave labor was unsuitable and costly for industrial production.

- Cotton exports provided stable profits, reducing incentive to industrialize.

- Low local demand and limited immigration constrained factory labor and markets.

- Southern investors avoided industrial risk in favor of plantation wealth.

- Northern textile interests benefited from the South’s agricultural economy remaining unchanged.

Why Didn’t the South Industrialize Before the American Civil War?

The South didn’t industrialize before the Civil War largely because its economic system, climate, labor structure, and social fabric all favored agriculture over manufacturing. This isn’t just a tale of “culture” or laziness, as some might claim. Instead, it’s a complex mix of geography, labor demands, market incentives, and investment choices. Let’s unravel this story layer by layer.

First, consider the climate. Southern summers are notoriously hot and humid — a tough environment for factory work. Before air conditioning became a thing, working indoors near all the machines and steam heat was downright miserable. Most industrial products, like textiles, had to be produced indoors. Combining Southern heat with factory labor was like trying to bake bread in a sauna—dangerous and exhausting for workers.

Geography also played a big part. The North had fast rivers—powerful and cheap sources of energy for mills and factories. The South’s rivers simply didn’t match up. Ports in New England were better equipped for shipping manufactured goods overseas, while Southern infrastructure focused mainly on exporting raw cotton. The soil was another factor: Southern lands favored plantations growing cash crops. Meanwhile, Northern soil and smaller farms supported more diversified agriculture, which went hand-in-hand with industrial development.

Economics sealed the deal. Local consumers in the South were on average poorer than in the North. This meant a smaller market for industrial goods. Why build expensive factories when people couldn’t afford the output? Southern wealth was tied up in agricultural exports; cotton was king, and Britain happily paid good money for that cotton. Surrendering fertile land to risky, unproven industries that might fail made no financial sense to Southern planters. Plantations were a gold mine, after all.

Plus, land ownership patterns reinforced this. Huge plantations dominated the South—vast tracts dedicated to cotton. In contrast, Northern land was divided among many smaller owners, which made land cheaper and easier to buy and repurpose for industrial ventures. So the very layout of land ownership nudged the South toward farming instead of factories.

Labor issues posed another massive hurdle. Industrial work needs skilled, flexible labor that factories can manage—hire, fire, retrain as needed. The South’s economy depended on slavery, which is brutally incompatible with industrial labor needs. Slave labor was expensive upfront since slaves had to be bought, fed, and housed. If workers were slow or unproductive, owners took the hit. But a factory boss could let European immigrant workers go if they weren’t cutting it—no upfront cost beyond wages. This isn’t just a little detail, it fundamentally shaped economic choices. Investing in factories made no sense since the labor system was built to support plantations.

Slavery also bred conservatism in investment strategy. Enormous wealth was tied up in enslaved people and land. Planters valued stability and profit over innovation. Convincing a planter to plow his fortunes into a risky manufacturing experiment? Nearly impossible.

Social and cultural factors mattered too, but not in the way stereotypes suggest. The South didn’t resist machines because of some cultural fear of technology. In fact, Southerners appreciated new inventions. The real reason was immigration—or the lack of it. The North welcomed waves of German, Irish, and other European immigrants, who filled factories and took low-skilled jobs. These ethnic enclaves created a labor pool ideal for industry. Southern society, steeped in slavery, was less attractive to immigrants. Some Europeans actively avoided settling where slavery was entrenched, fearing conflicts and rejection.

Now, let’s talk about entrepreneurship. The North boasted a vibrant mercantile community that encouraged risk-taking and startups. The South’s economy was stable but risk-averse, focused on preserving its agricultural riches. Entrepreneurial zeal thrives where failure is an option and reinvestment frequent—conditions absent in the Southern plantation system.

Interestingly, even Northern textile makers preferred the South to remain agriculturally focused. Northern mills relied on cheap Southern cotton to compete with their British rivals. Industrializing the South threatened to drive up cotton prices or create competition for Northern industries. This interdependence subtly reinforced the status quo.

Don’t think the South was industrially barren, though. Cities like Charleston and Atlanta had manufacturing hubs, including arms factories. Railroads existed but were mainly designed to funnel agricultural goods to ports. The mileage and network density paled compared to the North, limiting broader industrial connectivity.

Summary: The Perfect Storm that Kept the South Agricultural

- Climate challenges: Southern heat made factory work unbearable without modern cooling.

- Geographical drawbacks: Limited river power and port inefficiencies hampered industrial growth.

- Economic incentives: Plantation wealth in cotton outweighed uncertain industrial profits.

- Labor mismatch: Slave labor was expensive and inflexible, unlike industrial wage labor.

- Social factors: Few immigrants and less risk-taking culture slowed industry adoption.

- Investment conservatism: Planters clung to agriculture, avoiding risky manufacturing ventures.

- External pressures: Northern industries benefited from cheap Southern cotton and resisted Southern industrialization.

Put simply, the South’s choice—or rather, circumstance—to stay agricultural before the Civil War was less about *wanting* versus *not wanting* industry. It was more about a whole system of environmental, economic, social, and labor factors channeling its development in that direction.

Had these variables flipped—say, cheaper labor, less cotton demand, or a cooler climate—the South might have looked very different. So next time you wonder why the Southern states weren’t industrial powerhouses before 1861, remember: it’s not just one reason. It’s an intricate web of factors knitting together a story of geography, economy, labor, and culture.

What if the South did industrialize? Would the Civil War have taken a different shape, or even happened at all? Food for thought as history shows how deeply economics and environment shape a region.