The US pushed hard for a Japanese unconditional surrender mainly because Japan’s leadership was divided and fiercely resistant to any terms short of total defeat. This uncompromising demand aimed to secure a definitive end to the war, prevent prolonged conflict, and allow the Allies full control over Japan’s future. Although the eventual American occupation treated Japan relatively leniently—preserving the Emperor’s position and sparing the country from harsh punishment—the initial hardline stance was necessary to overcome entrenched Japanese opposition and to shape a stable postwar order.

Japanese leadership in 1945 was fractured. Hardliners in the military fiercely opposed surrender under any conditions. Some even staged a coup to stop the Emperor’s surrender announcement, demonstrating the high stakes inside Japan. Officers who resisted surrender often saw themselves as protectors of the Emperor’s honor and life.

This internal division made any negotiated peace uncertain. Though guaranteeing the Emperor’s position might have swayed some moderates, it was unclear if that alone would end resistance. Some hardliners might have pressed instead for retaining Japan’s empire or other political concessions. The Allies lacked a clear sense of what Japanese leaders would accept and did not trust negotiations with those they viewed as war criminals.

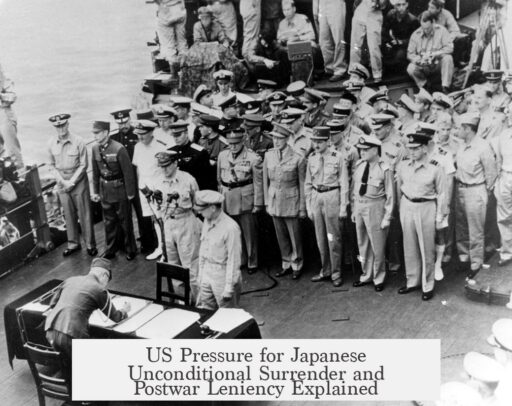

The Potsdam Declaration, issued in July 1945 by the Allied powers, outlined surrender terms that included Japan retaining sovereignty over its home islands under temporary occupation, eventual re-entry into world trade, disarmament, war crimes trials, and democratization. However, Japanese leadership essentially rejected these terms, seeking instead Soviet mediation. This refusal triggered two atomic bombings and a Soviet invasion of Manchuria, crushing Japan’s remaining military capability.

The US was not reluctant about using the atomic bomb. The successful Trinity test bolstered President Truman’s resolve to demand unconditional surrender without concessions. The bombings, combined with Soviet entry, swiftly forced Japan’s hand.

Another factor was geopolitics. With the Cold War emerging, the Allies wanted to end the war decisively before the Soviet Union gained more territory in East Asia. A rapid, unconditional surrender would prevent Soviet expansion and establish Western influence in Japan.

After the war, the US occupation took a surprisingly lenient approach. The Emperor remained on the throne in a ceremonial role. The Japanese government was restructured toward democracy. Harsh punishments or dismantling of the Emperor system did not occur. This leniency surprised some, yet it reflected a strategic choice to stabilize Japan as a peaceful, democratic ally.

There is speculation that guaranteeing the Emperor’s safety earlier might have avoided the atomic bombings. However, such a guarantee was difficult to offer without clear insight into Japanese factional politics. The Allies also lacked trust or willingness to negotiate with a regime seen as responsible for war crimes.

| Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Japanese resistance | Military factions opposed surrender, even refused broadcast; divided elite opinions. |

| Allied objectives | Demanded unconditional surrender to clear fascism and enable lasting peace and democracy. |

| Potsdam Declaration | Offered terms with sovereignty maintained but rejected by Japan. |

| Atomic bombings and Soviet invasion | Followed Japan’s rejection; forced surrender and shortened war. |

| Postwar leniency | US preserved Emperor’s role, promoted democracy for regional stability. |

- The US demanded unconditional surrender to overcome divided, resistant Japanese leadership.

- Allies sought a clear, decisive victory to prevent future conflict and ensure democracy.

- The Potsdam Declaration outlined surrender terms but was rejected by Japan.

- Atomic bombings and Soviet entry ended the war rapidly under these terms.

- Postwar occupation was lenient to stabilize Japan and prevent future militarism.

Why Did the US Push So Hard for a Japanese Unconditional Surrender When They Ended Up Going Relatively Easy on Them Anyway?

Short answer: The US demanded unconditional surrender from Japan due to fierce internal Japanese resistance, unclear leadership, and Allied strategic goals, yet after victory, the US adopted a relatively lenient approach to rebuild Japan into a stable, democratic ally.

This seeming contradiction puzzles many. Why go hardline on “unconditional surrender” only to go easy later? Let’s unpack that curious twist in history.

The Chaotic Japanese Leadership and Their Stubbornness

The first piece of the puzzle lies within Japan itself. The country’s leadership was far from united in 1945. Contrary to Hollywood’s neat portrayals, Japan didn’t have a single, all-powerful dictator calling the shots. Instead, multiple ministries, military factions, and the emperor’s inner circle squabbled over whether to surrender and on what terms.

Some Japanese officers felt surrender, especially if it meant losing the emperor’s position or worse, was unimaginable. In fact, a coup attempt almost derailed surrender because dozens of imperial guard officers and war ministry officials wanted to prevent the surrender announcement. Imagine the tension as war-weary leaders battled fanatics who believed resistance protected the emperor’s honor.

The emperor wasn’t just a figurehead; his status was sacred. Many hardliners genuinely thought preserving his throne justified continuing the war, regardless of the cost. But opinions were split. Some elites saw surrender as inevitable, while others demanded more concessions, like retaining parts of the empire or avoiding postwar prosecution.

So, was it possible to end the war with a deal guaranteeing the emperor’s position? Maybe. But any such concession risked encouraging hardliners to raise the stakes further, dragging on the conflict and increasing casualties. The US had to factor in this dangerous game of brinkmanship.

The Allies Wanted More Than Just a Surrender

Now, why did the Allies demand unconditional surrender, instead of negotiating upfront with Japanese leaders?

One reason was distrust. The Allies viewed much of Japan’s leadership as war criminals. Negotiating a deal with them felt like rewarding evil. Add to this the complexity and fragmentation of Japanese decision-making, and finding reliable negotiating partners seemed nearly impossible.

Another was hard-earned history. After World War I, the armistice with Germany happened too early. Germany’s defeat wasn’t complete enough, sowing the seeds for the infamous “stab-in-the-back” myth that contributed to WWII. The Allies wanted a definitive, clean victory to avoid history repeating itself.

This war was ideological. The Allies fought to safeguard liberal democracy against fascism’s brutal grip. Accepting a conditional surrender that left fascist elements in power was unacceptable. Instead, the plan aimed to dissolve ultra-nationalism and install stable, peaceful democracies.

The Potsdam Declaration and Japan’s Ambiguous Response

The July 1945 Potsdam Declaration embodied the Allies’ best offer. Japan could keep sovereignty over its home islands temporarily occupied by the Allies. In return, Japan had to disarm, undergo war crimes trials, and democratize.

But the declaration left some key points ambiguous—especially the emperor’s status and how long the occupation would last. This ambiguity reflected Allied strategic flexibility but also fueled Japanese suspicions.

Unsurprisingly, Japan reacted by “killing with silence.” Rather than an outright rejection, they stalled, hoping the Soviets might broker a better peace.

The Atomic Bombings and the Soviet Entry Changed the Game

Japan’s refusal triggered devastating consequences—the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria. The Soviet entry crushed Japan’s strongest remaining field army and dashed hopes for Soviet mediation.

Now, it’s crucial to understand: the US didn’t hesitantly drop these bombs hoping to force Japan’s hand with the least damage. The successful Trinity test emboldened President Truman. He saw no need to soften demands. The bombs were a tool to end the war decisively and quickly.

The Soviet factor was equally pressing. The Cold War was readying its opening act. The USSR had absorbed much of Europe. The US worried about Soviet influence expanding in Asia if Japan’s surrender dragged out. Securing an unconditional surrender expedited ending the war, limiting Soviet gains.

Could Things Have Gone Differently?

Many historians speculate: if the Allies had guaranteed the emperor’s safety and position upfront, could that have prevented the bombings?

Possibly. The emperor was never tried for war crimes and remained Japan’s ceremonial head of state postwar. A preemptive guarantee might have persuaded hardliners to accept surrender sooner.

But remember, the Allied leaders of 1945 lacked hindsight and certainty. They didn’t know exactly what the fractious Japanese leadership would accept. Plus, they weren’t keen on negotiating with leaders they considered war criminals. Playing safe with unconditional surrender avoided endless speculation and high risk.

The Postwar Reality: Leniency and Reconstruction

Here’s the twist—the US, after forcing unconditional surrender, turned out relatively kind. How so?

Firstly, the US preserved the emperor, but in a much weaker, symbolic role—an unexpected concession that bridged Japanese tradition with democratic governance.

Secondly, instead of punitive occupation or outright conquest, the US led a rebuilt Japan focused on democracy, economic revival, and peace. The US’s attitude shifted from punishment to partnership. This approach’ success helped Japan rise from ashes as a stable, democratic ally and economic powerhouse.

Lessons and Takeaways

- Unconditional surrender was a strategic stance: It avoided complicated, risky negotiations with a fractious enemy desperate to hold fragments of power.

- The ambiguity of demands allowed room for future leniency: Allies kept key points like the emperor’s fate flexible, paving the way for political solutions postwar.

- Military decisions consider geopolitical realities: The atomic bomb and Soviet involvement forced a rapid end to avoid further conflict and Stalinist expansion.

- “Unconditional” doesn’t always mean harsh postwar treatment: Winning the war required firmness; winning the peace demanded diplomacy and reconstruction.

So, why push so hard for unconditional surrender but then go easy? Because winning a complex war demands toughness—and winning a peace demands wisdom.

In the end, the US’s insistence helped end the war on its terms, avoided protracted bloodshed, and allowed a carefully managed transition from empire to democracy. The irony is striking: the world’s hardest demand paved the way for Japan’s gentlest postwar transformation.

“War is too important to be left to the generals” — but peace is even more important to be left without strategy and foresight.

What do you think—was the unconditional demand a necessary evil or an overreach? Could more diplomacy have spared atomic horror? Dive into history and weigh the complexity. After all, global peace often gets written in paradoxes.