The United States involved itself in the Philippine-American War primarily due to its imperialistic ambitions, strategic interests in the Pacific, racial attitudes, political pressures, and the desire to maintain its emerging global power status.

After the Spanish-American War, the U.S. acquired the Philippines, sparking a conflict with Filipino rebels who sought independence. The underlying causes of American involvement are complex and intertwined.

- Imperialistic Ambitions and Expansionism

By the late 19th century, the U.S. had achieved continental expansion and sought to establish an overseas empire. Many Americans, including influential politicians, believed the nation needed to expand beyond its borders to compete with European powers. This sense of imperial destiny motivated the U.S. to assert control over newly acquired territories, including the Philippines.

The Pacific Ocean had become a key area for great power colonial competition, especially regarding access to Asian markets like China. Possessing the Philippines gave the United States a strategic naval base in the Pacific, enhancing its influence and ability to project military power. Some American leaders called this a necessary step for the U.S. to assert its global status alongside established empires.

- Racism and Paternalism

Racial attitudes also influenced U.S. policy toward the Philippines. Many Americans doubted that Filipinos could self-govern. This paternalistic view justified keeping the islands as a colony under U.S. control to ‘civilize’ and prepare them for eventual democracy. President McKinley’s administration echoed these ideas, arguing that Filipinos were not ready for independence, despite having allied with the U.S. against Spain.

Such views reflected the broader racial prejudices of the era, portraying non-white populations as ‘savage’ and incapable of managing their own affairs. This paternalism helped justify the colonization to the American public.

- Strategic Location and Trade with China

The Philippines’ location was geopolitically crucial. Situated in the Western Pacific, the islands provided a vital naval base to maintain a U.S. military presence in the region. This presence was crucial to protect American interests and secure trade routes to China, an enormously important and resource-rich market at the time.

Controlling the Philippines enabled the U.S. to strengthen its foothold in Asia and participate actively in the ongoing competition among colonial powers for influence over China’s markets.

- Political and Public Opinion

Politicians who supported annexation strongly resisted Filipino independence once the U.S. took control. They argued that America could not simply abandon the territory after raising its flag. The public largely sided with political leaders like McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, providing a popular mandate to continue the war effort and suppress the Filipino rebellion with force.

McKinley even convened a commission to study the future of the Philippines, which concluded that the islands should remain under American tutelage until Filipinos were prepared for self-government. This official backing reinforced the decision to maintain control.

- Justification and Moral Reasoning

At the time, openly declaring imperialism was politically sensitive in the U.S. Leaders used moral rhetoric to justify the war without labeling it as such. Arguments emphasized civilizing the Filipinos and protecting them from chaos.

Once armed conflict began, abandoning the Philippines risked appearing weak domestically and internationally. Therefore, the U.S. chose to persist in suppressing the revolution rather than withdraw.

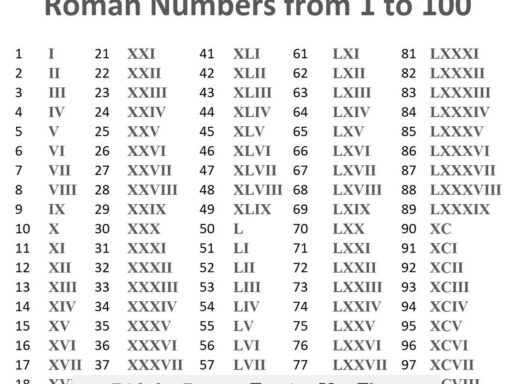

| Key Reasons for U.S. Involvement in the Philippine-American War |

|---|

| Imperial expansion and competition with European colonial powers |

| Strategic military location in the Pacific for naval presence |

| Racial and paternalistic beliefs about Filipino governance capacity |

| Political desire to retain acquired territory and assert global power |

| Public support combined with moral justifications for intervention |

The U.S. involvement in the Philippine-American War reflects a convergence of strategic calculations and ideological motives, notably desires for empire, racial attitudes prevailing at the time, and the demands of emerging geopolitical competition in the Pacific.

- The U.S. sought to expand its empire and compete with European powers.

- Control of the Philippines offered strategic military and trade advantages.

- Racial and paternalistic views shaped American policies toward Filipinos.

- Political leaders, backed by public opinion, resisted Filipino independence.

- Moral rhetoric masked imperial ambitions amid global power assertion.

Why Did the U.S. Involve Itself in the Philippine-American War?

The U.S. involved itself in the Philippine-American War primarily because it sought to establish and maintain an empire, driven by imperialistic ambitions, strategic interests, and a complicated mix of political, racial, and economic motives. Let’s unpack this tangled story that blends big power dreams, oceanic chess moves, and some eyebrow-raising rationalizations.

Empire-Building and the Hunger for Global Status

By the late 1800s, the U.S. had expanded westward across the continent. So, what was next? The answer: overseas territories. Many Americans, despite some dissenters—including President McKinley himself—felt the nation had to stretch beyond its borders. After all, the frontiers of the West were closed, and the country was eager to play in the big leagues of global power.

The Philippines stood out as a prime prize. European powers were flexing their muscles across the globe in a colonial frenzy, scrambling for markets and resources, particularly in Asia. The U.S. wanted in. Controlling the Philippines meant stepping into this imperialistic arena and signaling to the Old World that America was no pushover. Some politicians openly wanted to send a message that the U.S. was ready to assert itself on the world stage. The phrase “Where the flag has gone up, it must never come down” captured this stubborn resolve to hold on to new territories.

Strategic Location: The Power of Pinpointing the Pacific

Here’s a simple geographic fact that didn’t escape policymakers: The Philippines sit like a gatekeeper in the Pacific Ocean. Having a naval base nestled there could secure America’s Pacific presence and serve as a launching pad for trade, especially with booming China.

At that time, China seemed like a vast estate of opportunity. The U.S. dreamt of boosting trade access to Chinese markets and resources. Holding the Philippines meant easier access and influence in the region, something the U.S. Navy enthusiastically supported. Naval power was the currency of imperial success, and the islands’ strategic location made them a literal jewel in the Pacific crown.

Racism and Paternalism: The Elephant in the Room

Now, let’s be blunt: racial attitudes played a significant role in the decision to stay. Many Americans believed Filipinos were not ready for self-governance. This paternalistic viewpoint conveniently dovetailed with pro-colonial ambitions. The logic went like this: America would “help” Filipinos “grow up” into democracy, an idea that reeks of condescension today.

It wasn’t all high-minded ideals, though. Racism was near universal at the time. Filipinos were often viewed as “savage” people occupying “free land” ripe for American control. This mindset smoothed public acceptance of colonial rule and shaped policies that justified denying the Philippines immediate independence.

Political Pressure and Public Opinion: Hard to Back Out

Once U.S. troops took control after the Spanish-American War, American politicians faced a dilemma. Giving up the islands now would mean losing face—and that wasn’t an option. Public support bolstered this stance widely, led by leaders like McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Meanwhile, William Jennings Bryan’s opposition fell on deaf ears, cementing the commitment to hold and govern the islands.

McKinley even commissioned a study on what should be done with the Philippines. The commission concluded the U.S. should keep the islands but “teach” Filipinos how to govern properly. This approach gave the administration a moral fig leaf to cover what otherwise resembled pure imperial conquest.

Moral Gymnastics and Justifications

It wasn’t just about grabbing land. Many Americans wanted to avoid the label “imperialist” at all costs. So they performed mental and moral backflips to justify the Philippine annexation. They framed the occupation as a benevolent mission—”helping” a less developed people toward democracy.

But once the Filipino rebels responded with armed resistance, the U.S. faced a stark choice: withdraw and appear weak or double down. The decision was brutal suppression to maintain control. The slogan essentially became: We can’t just hand victory to rebels who fought alongside us against Spain. This added a dimension of military stubbornness to an already complex situation.

What Can We Learn From This?

The Philippine-American War wasn’t just a fight on an island. It was a story of ambition meeting reality. The U.S.’s involvement reflected a yearning to join the imperial game, tangled with racial prejudices and political will. It offers a cautionary tale about how power, strategy, and ideology can collide to shape history in unexpected ways.

Looking back, it’s clear this was far from a simple war for freedom or justice. It was a complex mix of desires: empire, security, trade, and image. The U.S. wanted to be a Pacific power, reach new markets, and claim a spot at the global table. But the cost was high—both for the Filipinos and for the moral clarity of the U.S.

Final Thought

Ever wonder how the U.S., born from revolution, became a colonial power itself? The Philippine-American War answers that question with a hard punch: imperial ambition doesn’t always wear the same face. It’s dressed in patriotism, strategic calculations, and sadly, a good dose of paternalism and racism. Understanding this history helps us better grasp America’s complex relationship with power and its own ideals.