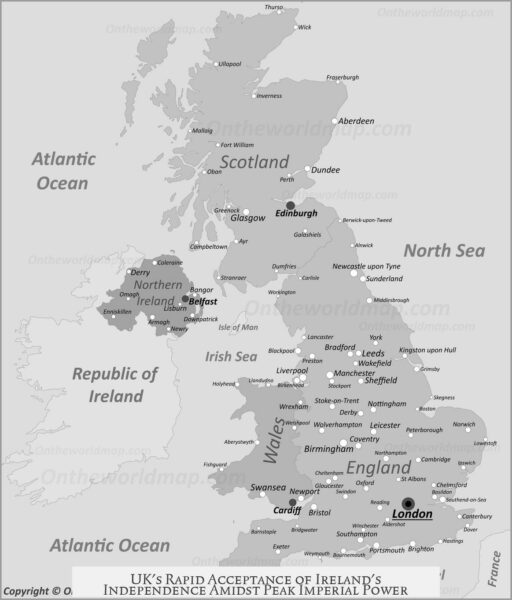

The UK’s acceptance of Ireland’s independence in the early 1920s resulted from a mixture of economic pressures, political realities, and lengthy conflict rather than swift consent at the British Empire’s peak. While the British Empire had vast territorial reach, its power and resources were stretched thin after World War I. The British government faced fierce Irish resistance, domestic divisions, and changing global attitudes about imperial rule, which combined to create conditions making full suppression untenable.

By 1922, the British Empire was at its largest geographic extent, yet that belies the empire’s actual condition. The First World War inflicted deep economic wounds on Britain. The nation emerged heavily indebted, especially to the United States, having shifted from being a global investor to one of the largest debtors. Inflation soared, and nearly 40% of government spending went toward interest payments alone. The emergence of new powers like the US and Japan challenged Britain’s global dominance, signaling a relative decline.

The political atmosphere post-war also favored change. President Woodrow Wilson’s advocacy for self-determination undercut absolute colonial control. Nationalist movements worldwide gained traction, while Britain saw internal debates over maintaining or adjusting imperial authority. Irish independence demands gained weight amid this shifting environment.

| Condition | British Empire in 1922 | Effect on Ireland Policy |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | Heavy war debts; reduced financial control | Limited capacity for prolonged conflict |

| Political | Rise of self-determination; divided public opinion | Pressure to negotiate and compromise |

| Military | Post-war fatigue; stretched forces | Less willingness for continuous violent repression |

Unlike typical colonies in far-flung areas, Ireland was integrated into the United Kingdom as a full constituent part, sharing a land border with Great Britain. British authorities had long sought to suppress Irish culture and language, fueling persistent and often violent rebellion over centuries. Battles and uprisings—from the Nine Years’ War to the 1916 Easter Rising—created a cycle of resistance and repression.

After the Easter Rising, Britain cracked down harshly, executing leaders and deploying infamous units like the Black and Tans, whose brutal tactics sparked outrage and increased Irish resolve. The War of Independence (1919–1921) exposed the limits of Britain’s ability to control Ireland through force alone. This prolonged conflict pushed Britain toward negotiation.

Within the UK, public attitudes were split. The British media and politicians debated the cost and practicality of continued conflict. Prime Minister David Lloyd George emerged as a pragmatic leader keen to secure peace without sacrificing imperial cohesion. His administration sought a compromise recognizing Irish autonomy yet maintaining symbolic connections to the Crown.

The resulting 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty granted Ireland dominion status akin to Canada. Ireland became the Irish Free State with constitutional freedom but retained ties through allegiance oaths, financial arrangements, and military restrictions. The treaty aimed to balance Irish sovereignty with imperial unity.

- Article 1 established dominion status comparable to Canada.

- Article 4 mandated Irish Parliament members swear allegiance to the Crown.

- Other clauses restricted naval rights and military capacity.

The treaty split Irish nationalists, sparking civil war. However, it marked Britain’s reluctant acceptance of Irish self-government driven by practical limits rather than colonial generosity. This agreement was the early model for future decolonization across the empire.

In summary, Britain did not quickly or willingly accept Irish independence as a gift. It was the outcome of:

- Economic exhaustion and declining global dominance.

- A historic pattern of Irish resistance combined with violent repression.

- Domestic political divisions and evolving attitudes toward self-rule.

- Pragmatic government leadership seeking to end costly warfare.

- The Anglo-Irish Treaty’s compromise reflecting emerging dominion status.

The case of Ireland became a precedent, illustrating how the British Empire’s sprawling, costly endeavors spurred gradual political concessions and the process of decolonization.

- The British Empire was territorially large but economically strained after WWI.

- Ireland’s proximity and integration made its status unique among colonies.

- Longstanding Irish resistance made outright suppression costly and unsustainable.

- British political and public opinion was divided on how to manage Ireland.

- The Anglo-Irish Treaty reflected a pragmatic compromise, granting dominion status.

- This set a pattern for future empire transitions toward independence.

Why Did the UK “Accept” Ireland’s Independence So Quickly When the British Empire Was at Its Height?

In 1922, the UK’s acceptance of Ireland’s independence was not a swift concession but rather a complex, grudging compromise shaped by war exhaustion, persistent Irish resistance, global political shifts, and pragmatic leadership. Despite appearances, the British Empire was not in its golden bloom of unshakable power but wobbling under serious pressures. Let’s peel back the layers and reveal why what looks like rapid acceptance was actually a hard-fought, strategic surrender.

First, imagine the British Empire in 1922—stretched across continents but financially and politically drained. The “height” of its territory does not mean the height of its strength. WWI’s aftermath had left the UK battered. The coffers were empty, interest payments swallowed nearly half of government spending, and inflation was rising. Meanwhile, the United States and Japan were elbowing into global influence. The British lion was still roaring but limping.

So, with a weak roar and heavy paws, the UK was suddenly faced with Ireland, not as a far-off colony where distance and oceanic separation bought time and oppression, but as a neighboring island with a population fed up with centuries of cultural suppression, political erasure, and violent crackdowns.

The Uniqueness of Ireland in the Empire

Unlike far-flung colonies subject to distant rule, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom itself—a union forged and forced over hundreds of years and marked by relentless attempts at eradicating Irish culture and language. The British response to Irish nationalism was harsh and consistent—wars, uprisings, executions, and the infamous Black and Tans’ brutal reprisals. Each rebellion—from the Tudor-era Nine Years’ War to the Easter Rising in 1916—added fuel to a fire the UK struggled to extinguish. So when Ireland’s fight re-erupted after WWI, Britain was caught between wanting control and recognizing the growing cost of conflict.

Perhaps history is the best teacher here. Wouldn’t any empire get tired of a neighbor that just won’t stop knocking down the fence? But what if the neighbor has support from the world’s emerging superpowers, like the United States, who now openly praised self-determination? Suddenly, the British government had to rethink stubbornness. It couldn’t wage endless war without deepening economic ruin and political isolation.

Politics, Public Opinion, and Pragmatism at Play

The UK’s political climate was tangled. The public was divided: some wanted to fight on regardless, others favored peace or compromise. Leaders such as David Lloyd George embodied this pragmatism. He knew the war with Ireland drained resources that the post-war UK could no longer afford. His approach was to find a “middle way” rather than insist on total domination.

“A faithful implementation of this Treaty will bring peace and happiness to Ireland,” Lloyd George declared, as he crafted what became the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This treaty was less a concession of defeat and more a calculated compromise.

Instead of a full Irish republic including all 32 counties, the treaty offered dominion status—familiar to the British Empire from Canada, Australia, and other former colonies. Ireland would remain within the Empire’s fold, owe allegiance to the Crown, but would gain significant autonomy.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty: A Compromise Fraught with Conflict

The treaty’s articles peppered the fine print with a balancing act:

- Article 1 established Ireland’s status like Canada’s dominion status—partial independence, not full sovereignty.

- Article 4 required an oath of allegiance to the Crown—a move that ripped Irish unity apart and triggered civil war within Ireland itself.

- Other provisions covered finances, naval defense, military limits, and control over Irish ports—the infamous “Treaty Ports,” a lingering British strategic presence.

For many Irish radicals, this was a bitter pill. Ireland fought for an outright republic, free from British rule. But the reality was harsh. The UK’s unwillingness to extend full independence forced the Irish delegation’s hands, under threat of renewed war. Signing the treaty was a reluctant acceptance of partial freedom rather than total victory.

Understanding the “Quick Acceptance” Myth

Was this acceptance truly quick? Not at all. Look at the decades preceding it—a relentless cycle of rebellion, suppression, and political maneuvering. The UK fought fiercely and brutally before stepping to the negotiating table. But post-war realities, increasing nationalist sentiment worldwide, and diplomatic pressures, especially from the US advocating self-determination, squeezed the UK’s options.

This moment foreshadowed what would become a common story across the British Empire: suppression of resistance, harsh crackdowns, the rise of national movements, and eventual British fatigue leading to negotiated retreats. Ireland’s partial independence was essentially the first domino.

What Can Modern Readers Take From This?

Want practical wisdom from this historical saga? It’s simple: even the mightiest powers face limits. Exhaustion—whether economic, political, or social—can force compromise. And neighbors with stubborn resilience and external support can dramatically alter political landscapes.

For those facing conflicts today, Ireland’s story shows that perseverance, coupled with favorable global tides, can generate change. For governments, it’s a lesson in pragmatism: rigid control isn’t always sustainable.

Could this scenario repeat with the UK and its territories? Possibly, but every historical moment is unique. Still, understanding history’s arc helps us predict the ebbs and flows of power and independence.

Summing Up

The UK’s so-called “quick” acceptance of Irish independence was a strategic retreat cloaked in pragmatism and compromise, not an impulsive act of generosity. The empire’s economic depletion, political realities, and international pressure shaped this outcome. Centuries of Irish resistance and cultural survival made the cost of continued conflict too high.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty marked not the end of British influence over Ireland but a redefinition—a midway step reflecting new global norms and internal exhaustion. It set a blueprint for decolonization that would ripple through the next century, a story of imperial contraction shaped by local determination and global change.

So the next time someone says, “The UK just accepted Ireland’s independence quickly,” you can smile knowingly and say, “Not so fast — it was a decades-long saga of struggle, pragmatism, and the political realities of a world forever changed by war.”