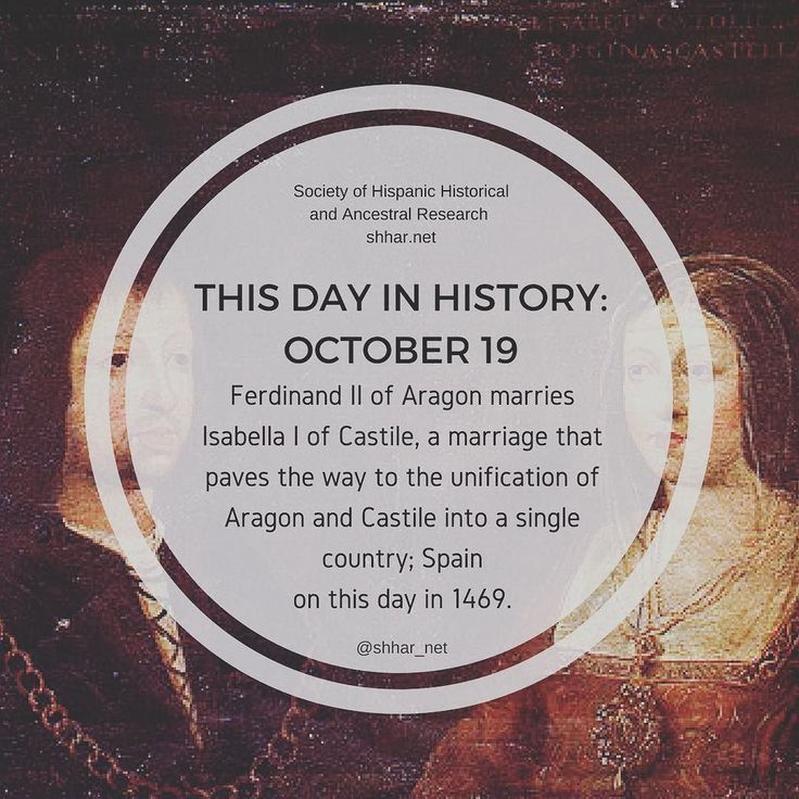

The kingdoms of Castile and Aragon became the Kingdom of Spain due to a dynastic union initiated by the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabel in 1469, which united the crowns but kept their administrations separate for centuries. The title “King of Spain” only emerged later, under the Bourbon dynasty, when centralization efforts abolished the old institutions and traditional kingdoms.

The union began with Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel of Castile marrying. They ruled jointly but maintained their realms as distinct entities. Each kingdom had its own laws, institutions, and administrative systems. This arrangement is known as a dynastic union because only the monarchs were united, not the institutions.

For about 250 years, Castile and Aragon functioned under a dual monarchy. One of the early joint institutions was the Spanish Inquisition, which spanned both kingdoms. Upon Isabel’s death, their daughter Juana and later Charles I continued the co-monarchy system. Charles became the sole monarch only after Juana’s death in 1555.

The formal title “King of Spain” did not appear until the end of the Habsburg dynasty in 1700. Philip V of the Bourbon family was the first monarch to adopt this title. Before that, the term had little or no legal or jurisdictional significance.

The Bourbon dynasty enacted broad reforms to unify and centralize governance. These reforms dismantled the traditional kingdoms’ separate institutions and consolidated power under a single Spanish crown. This changed the political landscape from a dynastic union to a centralized state known as Spain.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1469 | Marriage of Ferdinand and Isabel—dynastic union |

| 1555 | Charles I becomes sole monarch after Juana’s death |

| 1700 | Start of Bourbon dynasty; formal use of “King of Spain” |

| 18th century | Bourbon reforms abolished old kingdoms’ institutions |

- The union was personal via marriage, not political integration.

- Separate administrations lasted centuries despite shared monarchs.

- The title “King of Spain” appeared only with Bourbon centralization.

- Bourbon reforms centralized the state, ending medieval kingdoms’ autonomy.

Why Did the Kingdoms of Castille and Aragon Become the Kingdom of Spain Instead of Keeping Their Former Names and Titles?

In a nutshell, the transition from separate kingdoms of Castille and Aragon to a unified Kingdom of Spain was not immediate, but the combined effects of dynastic marriages, political shifts, and Bourbon reforms gradually turned a collection of kingdoms into a centralized state called Spain, especially after 1700.

So, how did this transformation unfold? Let’s unfold the dense tapestry of history but keep it breezy.

When Ferdinand of Aragon married Isabel of Castille in 1469, it seemed like a royal gossip-worthy union more than a political merger.

Dynastic Union: Marriage Over Merger

This marriage formed what historians call a dynastic union. That’s fancy talk for two monarchs ruling jointly over their individual kingdoms but without fusing the kingdoms themselves. Ferdinand was king of Aragon, Isabel queen of Castille; they ruled side by side, like co-CEOs presiding over their respective companies. The catch: the kingdoms themselves stayed largely independent, each keeping their own laws, customs, and institutions.

Think of it as two neighboring houses owned by a married couple but with separate mailboxes, kitchens, and heating systems. Their union created a powerful alliance but didn’t erase individual identity overnight.

Separate Administrations and Lingering Independence

This arrangement lasted for quite a stretch—over 250 years. During this time, the kingdoms remained distinct politically and administratively.

Funnily enough, one of the earliest shared institutions was the infamous Spanish Inquisition, showing that cooperation could exist even in the darkest of measures.

Even though the monarchs were shared, Castile and Aragon continued running their own governments. This setup might confuse anyone expecting an instant political merger, but it’s crucial to understand.

Succession Through Co-Monarchy

The royal relay continued. After Isabel’s passing, her daughter, Juana, inherited Castile, sharing rule with Ferdinand. Then Juana and Charles I of Spain (also Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire) co-ruled. Only after Juana died in 1555 did Charles become the sole monarch of both kingdoms.

Still, despite one person wearing both crowns, the two kingdoms didn’t lose their identities yet. Not quite a unified kingdom but a step closer.

The Late Emergence of the “King of Spain” Title

Now, here’s a twist that might surprise you: the official title “King of Spain” didn’t exist during Ferdinand and Isabel’s era.

It seems that this title only popped up at the end of the Habsburg dynasty around 1700, during the rise of the Bourbons. Philip of Anjou, the first Bourbon king of Spain (Philip V), is generally credited with embracing and popularizing this title.

Early on, if the title “King of Spain” was even tossed around, it didn’t carry much real legal or jurisdictional punch. It was more of a convenient label than a sign of administrative unity.

Bourbon Reforms: The Real Game Changer

Everything changed when the Bourbons took charge. These kings saw the messy patchwork of kingdoms as a stubborn mess.

They launched sweeping reforms aimed at centralizing power, streamlining administration, and doing away with the centuries-old institutions that kept Castile and Aragon separate entities.

The Bourbon reforms drastically reduced the authority of historical kingdoms. Old medieval and Habsburg political structures were abolished or reformed to fit a unified vision. This made “Spain” an actual kingdom with centralized institutions, laws, and identities.

The Story Behind Changing a Name

Why was ditching the old names important? A country’s name reflects its unity and authority. Sticking with Castile and Aragon would imply a divided land of competing interests.

Adopting the name “Spain” signaled a new era—a sovereign, centralized state rather than a loose-knit dynastic patchwork.

It helped rally people across the former kingdoms under one banner—to simplify governance, unite identity, and strengthen Spain’s position as a European power.

What Can We Learn From This?

- Political unions through marriage don’t guarantee immediate unity in governance.

- Titles and names evolve slowly and often reflect power changes more than actual territory changes.

- Strong central authority tends to emerge only when rulers actively dismantle older, decentralized institutions.

Think of it like blending ingredients. Initially, it’s a layered dessert with distinct tastes. Only when mixed properly do you get a uniform flavor—yum, the Kingdom of Spain.

Final Curiosity: Did People Instantly Call It Spain?

Probably not. Locals might have clung to their regional identities for generations. Imagine telling a Madrileño they’re not from Madrid but just “Spain.” Ouch.

But over time, political convenience and centralized communication helped the new name stick.

In Closing

The kingdoms of Castille and Aragon didn’t vanish overnight. Their journey toward becoming “Spain” spans centuries of dynastic marriages, co-monarchies, and complex politics. The real push came with Bourbon reforms, which abolished old structures and centralized governance under the banner of Spain.

Next time you hear “Spain,” remember it’s a relatively modern identity forged from the slow dance of history’s dynastic deals and political overhauls.

Why did Castile and Aragon unite under the Kingdom of Spain despite separate administrations?

The marriage of Ferdinand and Isabel united their crowns through a dynastic union. Their kingdoms stayed separate in law and administration for centuries, linked only by shared monarchs.

When did the title “King of Spain” first come into use?

The title “King of Spain” emerged late, around 1700 under the Bourbon dynasty starting with Philip V. Before that, the monarchs ruled different kingdoms but did not use a unified title.

Did the “King of Spain” title originally change governance or institutions?

No. Even when the title appeared, it carried no new jurisdictional power. The traditional kingdoms kept their own laws and institutions until Bourbon reforms.

How did Bourbon rule affect the separate kingdoms of Castile and Aragon?

Under the Bourbons, especially after 1700, traditional kingdoms and their institutions were abolished. The crown centralized power, creating a unified state known as Spain.

Why wasn’t the Kingdom of Spain established immediately after Ferdinand and Isabel’s union?

Because their union was personal and dynastic, not institutional. Castile and Aragon had distinct laws and power structures, so Spain grew gradually with later reforms.