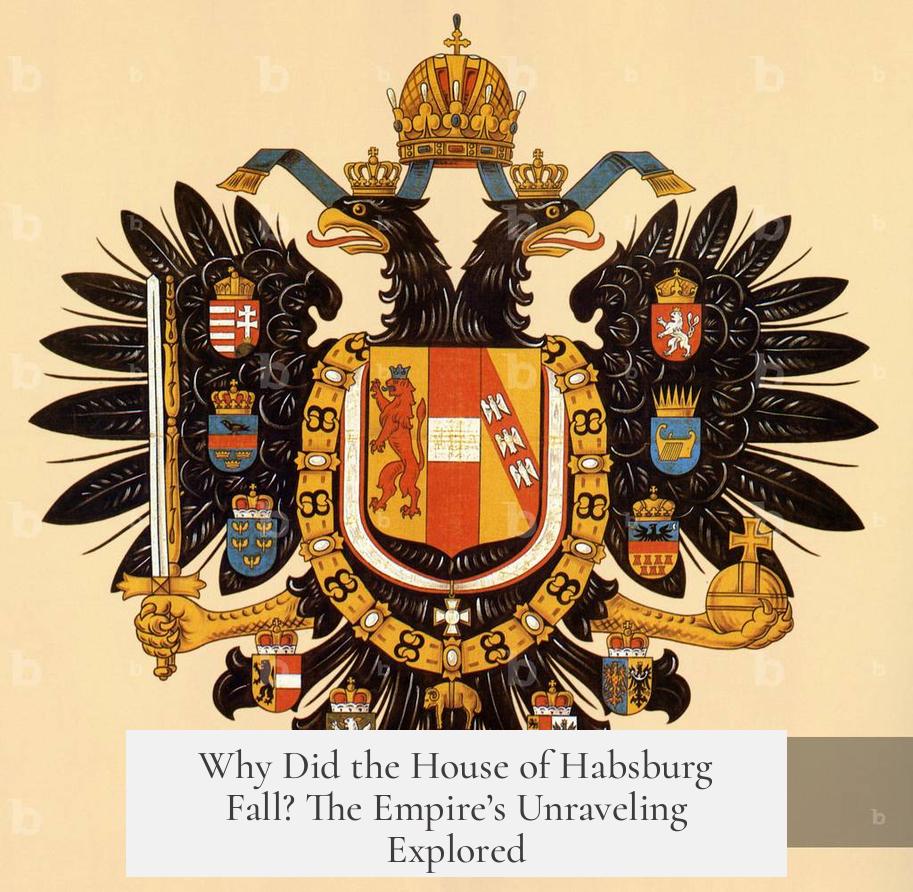

The House of Habsburg fell due to a combination of growing nationalist movements, administrative inefficiencies, external pressures, failed reforms, and the consequences of World War I. These factors eroded the traditional dynastic loyalty that had held its diverse empire together, resulting in its collapse.

The Habsburg Empire once united various groups under one dynasty. This approach became outdated by the early 20th century. Loyalty to a ruling family no longer sufficed to maintain cohesion among diverse ethnic, linguistic, and religious communities. Nationalism gained strength, promoting ideas of self-determination and cultural unity within nation-states. The empire’s many peoples started seeing themselves as separate nations rather than subjects of a monarchy.

Ethnic groups like the Czechs or Croats lacked political power. Only German Austrians and Hungarians had substantial control. This imbalance created resentment among other nationalities. Calls for equality and recognition grew louder. The empire’s failure to address these demands deepened fractures.

Managing such diversity proved difficult. The dual monarchy system required the prime ministers of Austria (Cisleithania) and Hungary to agree on policies. Their interests often clashed. This governance structure slowed decision-making and hindered effective rule. Administration was also complicated by the empire’s eleven official languages, which obstructed communication and policy enforcement. For comparison, colonies with more centralized governments or culturally homogeneous populations managed internal affairs more efficiently.

External pressures worsened these internal challenges. The death of Emperor Franz Joseph, who symbolized stability due to his long reign, removed a unifying figure. His successor lacked similar authority. The empire endured military defeats, weakened morale, economic hardship, and growing unrest. Populations demanded rights and voiced discontent over hunger and mismanagement.

World War I was a decisive factor in the Habsburg decline. The empire entered the war bound by a fragile coalition of nationalities. As the conflict dragged on, nationalist ambitions clashed with the monarchy’s unity. The war drained resources and exposed internal weaknesses. Ultimately, defeat in the war discredited the dynasty and accelerated its collapse.

Attempts at reform came too late. Archduke Franz Ferdinand, whose assassination triggered the war, recognized the need for reform. He planned to transform the empire into a confederation of three equal peoples: Germans, Hungarians, and Slavs. His vision aimed to grant Slav groups more autonomy, potentially stabilizing the empire. However, Serbian nationalists opposed this idea, fearing it would weaken their goal of uniting South Slavs under Serbia. This opposition contributed to the outbreak of war and the failure of reforms.

The Habsburgs’ decline also reflects differences between the Spanish and Austrian branches. The Spanish Habsburgs suffered long before the 20th century due to imperial overstretch and harmful inbreeding practices. These factors weakened their dynasty, leading to replacement by the Bourbons.

Meanwhile, the Austrian Habsburgs shifted their ambitions after setbacks in central Europe. The Thirty Years’ War and the Peace of Westphalia limited their control over the Holy Roman Empire. Instead, they focused eastward on Hungary and Transylvania. Despite some Mediterranean acquisitions after the War of Spanish Succession, they faced continuous threats from the Ottoman Empire and rising Protestant powers like Prussia. This constant pressure required resources, contributing to the empire’s strains.

| Factor | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Nationalism | Rise of ethnic groups demanding self-rule. | Undermined imperial unity. |

| Inefficient Administration | Dual government with conflicting Hungarian and Austrian leadership. | Slowed decision-making and governance. |

| World War I | Military defeat and resource depletion. | Weakened monarchy and shifted power balances. |

| Failed Reforms | Unrealized plans to grant autonomy to Slavs. | Lost chance to stabilize the empire. |

| Loss of Strong Leadership | Death of Emperor Franz Joseph. | Reduced monarchial influence. |

The fall of the House of Habsburg is a classic example of how outdated dynastic loyalty can erode when stronger social forces like nationalism and ethnic identity emerge. Its complex empire was difficult to administer efficiently. External military pressures and internal dissatisfaction further accelerated its disintegration. Ultimately, the dynasty could not adapt quickly enough to the changing political environment and collapsed after World War I.

- Nationalism eroded loyalty to the dynasty among diverse empire populations.

- Inefficient dual administration slowed governance and worsened ethnic tensions.

- World War I military defeat exposed and intensified imperial weaknesses.

- Failed reforms by Archduke Franz Ferdinand came too late to save the empire.

- Death of Emperor Franz Joseph removed a stabilizing influence.

Why Did the House of Habsburg Fall? The Empire’s Unraveling Explored

The short answer? A tangle of rising nationalism, administrative headaches, and the havoc of World War I broke the once-mighty House of Habsburg. But that’s only the tip of the iceberg. This sprawling story winds through politics, culture, war, and even genetics. Buckle up, history fans — the fall of the Habsburgs isn’t just about losing a war; it’s a full-scale saga of decline.

The Habsburg empire wasn’t just any monarchy; it was a multiracial, multiethnic, and multilingual empire spanning vast lands. All seemed bound by loyalty to the dynasty itself, an idea inherited from a by-gone era. But here’s the catch: by the early 20th century, this *loyalty* skeleton wasn’t enough to hold together a patchwork quilt of peoples with vastly different languages, religions, and customs.

Imagine a dinner party where everyone speaks a different language—and only two groups get invited to serve their favorite dishes. In the Habsburg empire, German Austrians and Hungarians were the serious players, with power concentrated in their hands. Meanwhile, Czechs, Croats, Slavs, and many others didn’t control their own governments or even have a chance at true representation.

This imbalance highlighted one big flaw: lack of cultural homogeneity. The age of nationalism had dawned by 1914. People no longer felt bound by a distant monarch but yearned for self-rule and identity recognition. Nationalism grew strong, like a weed choking the old imperial garden. People wanted their own parliaments, not just a spot at the imperial table.

Internal tensions brewed further because the empire’s administrative machinery was a hot mess. Think about it—two prime ministers, one for Hungary and another for the rest (known as Cisleithania), had to agree before making decisions. It’s like having two captains steering a ship in opposite directions. Such constant negotiation slowed governance down and bred inefficiency.

Also, the empire juggled eleven official languages. Bureaucracy got bogged down in translation and misunderstanding. Dealing with serious affairs in so many tongues, under one roof, fueled frustration and red tape. No wonder reforms stalled and progress felt as slow as a horse-drawn carriage on a muddy road.

On the international stage, the Habsburgs had their share of problems too. The Spanish Habsburgs struggled centuries earlier with “imperial overstretch.” They tried to defend scattered territories worldwide, like an overworked parent trying to juggle ten kids at once. Add in extensive inbreeding within the family, weakening their health over generations, and the Spanish line eventually crumbled — replaced by the Bourbons of France.

The Austrian Habsburgs had their ambitions checked in the 17th century during the Thirty Years’ War and the resulting Peace of Westphalia. These treaties curtailed their ambitions within the Holy Roman Empire, pushing them to refocus on eastward expansion towards Hungary and Transylvania. Still, they faced threats from the Ottoman Empire and the rising power of Protestant states like Prussia.

Fast forward to the 20th century, things got even more complicated. Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir whose assassination triggered World War I, understood the empire was in trouble. He had plans to reform it, creating a confederation that gave equal standing to Germans, Hungarians, and Slavs. It was a clever idea to calm nationalist tensions—but it never came to be.

Why? Because some disagreed hard. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip, later claimed that his group feared a more content Slavic population inside the empire would crush Serbian hopes of leading all South Slavs separately. This shows how complicated the nationalist issues were—reform was on the table, but not everyone wanted it.

Then came World War I—a brutal, chaotic disaster for the empire. Plagued by bitter military defeats and dwindling morale, the Habsburg rulers lost their remaining grip. The death of Emperor Franz Joseph, who had reigned for over 68 years and served as a unifying figure, left a vacuum. New leaders couldn’t command the same respect.

Meanwhile, hunger, hardship, and internal strife stirred resentment. People demanded the right to choose their own futures, not just accept a crumbling empire’s hierarchical order. The war amplified these grievances, and loyalty to the dynasty waned.

When the empire lost the war, the final blow came swiftly. Without military victory or the old monarch’s glue, the empire shattered into independent nations overnight. The Habsburgs lost control, collapsing under the weight of forces that had grown too vast and complex to manage.

What Can We Learn From This?

The fall of the House of Habsburg teaches us that even the grandest empires crumble without adapting to changing times. Relying on outdated loyalty, ignoring rising nationalism, and struggling with inefficient governance can sink a state. Multiethnic empires need more than royal family ties—they need fair representation and unity through shared interests, not just royal decrees.

If you’re leading an organization, maybe this means avoiding favoritism and listening to your team’s diverse voices. Ignoring internal frictions and refusing to reform? That’s a fast track to collapse. Also, don’t underestimate the power of fresh leadership—Franz Joseph outlived his usefulness, and the next generation couldn’t hold the empire together.

So, the House of Habsburg fell because the old ways couldn’t hold fast in a rapidly changing world. Nationalism tore at the fabric, inefficient administration tangled the threads, and war ripped the cloth apart. It’s a vivid reminder that no dynasty, big or small, is immune to history’s relentless march.

Ready to dive deeper? Explore how the Habsburgs’ fall influenced the rise of new nations like Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Or compare the Habsburg administrative challenges with those in the British Empire’s handling of diverse colonies. History’s lessons are immense and endlessly fascinating.