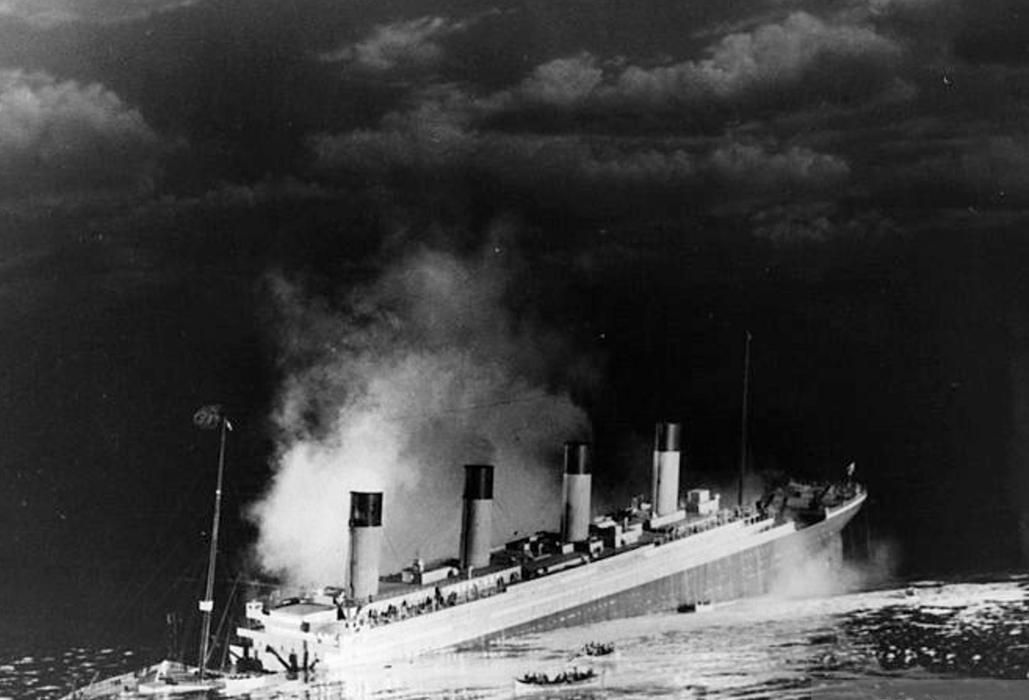

Some people jumped from the sinking Titanic instead of trying to stay dry because they believed it increased their chance of survival, they feared the ship dragging them underwater, or they preferred a quicker death over prolonged suffering. These decisions varied by individual circumstances and were shaped by limited knowledge of hypothermia and the unfolding situation in the final minutes before the ship sank.

The sinking Titanic was not a long, chaotic event for most passengers. Most of the drama occurred in the last 5 to 10 minutes before 2:20 a.m. Survivors described a growing list to the port side and an increasing urgency in those final minutes. Some passengers began to jump from the stern, hoping to reach lifeboats or float on debris. A notable firsthand observation by survivor Jack Thayer reveals he contemplated jumping multiple times but was deterred by fears of hitting the water hard and by others urging him to wait.

One primary reason some chose to jump was to avoid any chance of being pulled underwater by the ship’s sinking. Although significant suction is usually considered unlikely—multiple accounts, including that of Titanic’s chief baker Charles Joughin, showed negligible suction—panic and fear made this concern very real for many. The belief that the ship could drag them under created a powerful incentive to leap into the water early.

Others jumped with the hope of reaching a lifeboat or using floating wreckage to stay afloat until rescue. Survivors who jumped sometimes stripped down to clothing that would not impede swimming. Thomas Ranger and Frederick Scott, for example, climbed down to a lifeboat while others, like Frederick Hoyt, claimed to have been encouraged by Captain Smith to swim toward a boat when one appeared. However, no one who jumped into the water without boarding a lifeboat survived, underscoring the high risks involved.

Decisions to jump also reflected an acknowledgement of the dire situation. Some passengers assessed that staying aboard longer only postponed inevitable death by hypothermia or drowning. With approximately three minutes remaining before Titanic’s final plunge below the surface, some viewed jumping as an attempt for quicker, if riskier, survival. Records from other disasters suggest that some individuals preferred immediate death to slow suffering, a choice that likely influenced some on Titanic too.

Individual circumstances played a key role. Swimming ability, physical condition, and mental state influenced choices. George Rheims jumped but his brother-in-law stayed onboard because he could not swim; Rheims survived, his relative did not. Such contrasts show that personal risk calculations differed widely.

Limited knowledge of cold-water dangers added complexity. At the time, hypothermia and cold shock were poorly understood. Passengers might have overestimated their chances of survival in icy Atlantic waters, assuming lifejackets and debris would suffice until rescue. This optimism, though often unfounded, contributed to decisions to jump rather than remain on the sinking ship.

“The list to the port had been growing greater all the time. About this time the people began jumping from the stern… even then we thought she might possibly stay afloat.” – Jack Thayer

| Reason for Jumping | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Avoiding Suction | Fear of being pulled underwater by the sinking ship, despite minimal actual suction. |

| Reaching Lifeboats | Belief that swimming or floating wreckage provided a better chance for rescue. |

| Quick Death Preference | Choosing immediate death over prolonged suffering from cold water or drowning. |

| Individual Capacity | Swimming skill and physical condition influenced jumping decisions. |

| Misinformation on Hypothermia | Lack of awareness about dangers of cold water affected risk perception. |

The timing of the jumps was critical. Most occurred in the last few minutes leading up to Titanic’s final submersion. For some, it was a last resort when it became clear the ship would not stay afloat. The hope was to board lifeboats or find floating debris amid the chaos.

To sum up:

- People jumped fearing the ship would drag them down or to reach safety via lifeboats or debris.

- Some believed quick immersion was preferable to prolonged drowning or hypothermia.

- Jumping often took place in the final minutes of the sinking when options were limited.

- Individual decisions were shaped by swimming ability, personal risk assessment, and limited cold-water survival knowledge.

- No one who jumped without entering a lifeboat survived, highlighting the grave risks.

Why Did Some People Start Jumping from the Sinking Titanic Instead of Trying to Stay Dry for as Long as Possible?

Some passengers on the Titanic decided to jump into the icy Atlantic waters rather than stay aboard the sinking ship because they judged that their chances of survival were better if they left earlier, despite the grave risks. This choice to jump wasn’t just a reckless impulse; it was a calculated, desperate gamble shaped by fear, hope, and circumstance. Let’s dive into the details, unraveling why certain souls chose a watery plunge over clinging to the doomed vessel.

Facing the Sinking Titanic: To Jump or Not to Jump?

When the Titanic was sinking, there was a critical moment for everyone aboard. The ship wasn’t immediately going down in a flash; the horrific images of chaos mostly come from the last 5–10 minutes before she slipped beneath the waves after 2 a.m. For the majority of the night, the drama was… well, surprisingly dull for a disaster movie. But as the ship listed heavily toward the port side, the tension surged, and some passengers made life-or-death decisions.

You might wonder, did the frightening spectacle of a giant ship going under suck people down? Interestingly, no. According to eyewitness testimony, including that of Joseph Boxhall and second officer Charles Lightoller, the suction from a sinking ship isn’t strong enough to drag swimmers under. Lightoller himself said he “rode the stern down like an elevator” and stepped off gently without getting his hair wet. So, fears of drowning by the ship’s suction, though common, were exaggerated.

Why Jump into Freezing Water at All?

The simplest answer is: jumpers thought it was their best shot.

Some people saw the sinking ship as a trap. The looming threat wasn’t just the cold water, but the idea of being dragged down, trapped inside or near the wallowing hulk. These jumpers probably imagined that by putting some space between themselves and the ship, they could increase their survival chances. They were hoping to swim to lifeboats that were already afloat, or grab onto floating debris. Unfortunately, no one who jumped and failed to reach a lifeboat survived, so hindsight shows this was an enormous risk.

Another factor was grim: some passengers might have accepted their fate and chose to face death instantly rather than endure a slow and painful demise on the slowly sinking vessel. Many historical disasters show this tragic pattern. The cold, combined with fear and confusion, can push people toward drastic actions.

Survivor Stories Shine Light on These Decisions

Jack Thayer, a Titanic survivor, observed the increasing list and saw people jumping from the stern in the final minutes. He almost jumped himself, three times. But he hesitated, pulled back by companions warning him to wait. He recounts the final moments with a mix of dread and disbelief, hoping the ship might stay afloat longer. Yet, the minutes slipped away, and eventually, even he climbed down into the freezing ocean.

Meanwhile, you had people like Thomas Ranger and Frederick Scott, who jumped—but not haphazardly. They climbed down the davit ropes to lifeboats, showing a level of planning amid chaos. Others received encouragement from Captain Smith himself; Frederick Hoyt recalled the captain urging him to jump and swim to safety. Such moments reveal how choices varied widely, blending fear, hope, and strategy.

Individual Circumstances Made All the Difference

The Titanic tragedy reminds us that human survival often boils down to personal factors and split-second decisions. George Rheims jumped overboard, stripping down to his underwear, ready to endure the icy plunge. His brother-in-law did not; he stayed on board because he couldn’t swim and did not survive. These stories highlight how things like swimming ability and readiness affected who decided to jump.

It’s important to remember that knowledge about hypothermia and cold shock was scarce in 1912. Passengers had little idea how quickly the 28°F (-2°C) water could sap strength and end life. Many clung to the hope their lifebelts and wreckage might keep them afloat until rescue arrived, which often turned out tragically mistaken.

Jumping vs. Remaining on the Titanic: Was There a Right Choice?

Is it better to jump early or wait it out on a sinking ship? Sadly, neither option was ideal. The limited lifeboats meant many waited in vain, hoping for rescue. Those who jumped faced a brutal cold death unless they found a lifeboat or floating wreckage quickly.

The fact that almost no one survived in the water without a lifeboat paints a harsh reality. But it’s worth asking: if faced with that choice, what would you do? Would you gamble on jumping, risking an icy plunge, or stay aboard hoping for rescue, knowing the ship is plummeting to the bottom?

Takeaways from Titanic’s Tragic Decisions

- Jumping wasn’t caused by the myth of deadly suction, but by fear of the ship’s final grip and hope to reach safety.

- Each jumper weighed risk differently, influenced by swimming ability, physical condition, and knowledge of hypothermia.

- Many faced an agonizing choice: instant death in freezing water or prolonged death aboard the sinking Titanic.

- Those who planned their jumps, like descending ropes to lifeboats, had better survival chances.

- The Titanic sinking highlights how disaster responses unfold uniquely for every individual, shaped by circumstance and courage.

So next time you picture the Titanic disaster, consider this: the people who leapt didn’t simply “give up.” They made noble, horrifying choices, betting against time and the sea. Their stories remind us of the profound complexity behind survival.