Agriculture took so long to be implemented because early human societies prioritized hunting and gathering, managed their environments effectively without farming, and faced technological and knowledge limitations that delayed full-scale cultivation. The shift was gradual, complex, and involved proto-agricultural practices spanning thousands of years rather than a sudden change.

Hunter-gatherers initially viewed agriculture as labor-intensive and less rewarding compared to their existing lifestyle. Evidence shows that early hunter-gatherers were often taller and better nourished than early farmers. Farming required intense work and led to less leisure time, making it an unattractive option unless necessary.

These early peoples possessed deep ecological knowledge. Their familiarity with plant cycles and local ecosystems allowed them to manage wild resources without formal agriculture. They used techniques like controlled burning to encourage the growth of desirable plants. Such strategies enabled them to thrive while maintaining a mobile lifestyle. They adjusted their movements to follow seasonal plant yields rather than settling permanently, which delayed the need for farming.

Anthropologists no longer consider hunter-gatherers primitive. Their knowledge was sophisticated, and the adoption of domesticating plants and animals was not an instant realization. It was not ignorance but rather practical adaptation to environmental changes after the last Ice Age that pushed humans toward agriculture. The move to farming is sometimes seen as “a step in the wrong direction” due to lower yields and increased labor, but it became necessary as population pressures and climate shifts reduced wild resource availability.

The transition to agriculture was not a sharp break but a slow evolution. Early humans practiced what is now called proto-agriculture, where they planted seeds but did not abandon mobility. Instead, they would plant seeds at one site, move away, and return months later to harvest naturally grown crops. This form of cultivation allowed gradual learning about plant growth and selection without giving up nomadism.

- Proto-agriculture included burning unwanted vegetation to help useful plants grow.

- It involved partial harvesting with intentional replanting, encouraging regrowth of wild plants like yams.

- Such methods enhanced food supplies and taught early peoples how to cultivate plants effectively over centuries.

This accumulation of knowledge took hundreds, possibly thousands, of years. Only with this deep biological and ecological understanding could humans develop the full-scale agriculture needed to support dense populations.

Technological limitations also slowed the process. Basic farming tools, such as the hoe, required significant craftsmanship. Making these tools demanded skills in shaping wood, working with organic materials, and later metals. Early humans lacked modern workshops and tools, so producing reliable farming implements took generations.

Acquiring the know-how to make tools and manage crops was a lengthy process. The shift from gathering to farming involved trial, error, and transmission of knowledge through many generations. This explains why agriculture did not emerge overnight or even within a few centuries but spanned millennia.

Hunter-gatherer societies maintained efficient survival strategies. Their deliberate avoidance of farming was rational, based on current conditions and resource availability. The eventual adoption of farming reflected a response to changing climates, population growth, and resource depletion, rather than a simple lack of intelligence or curiosity.

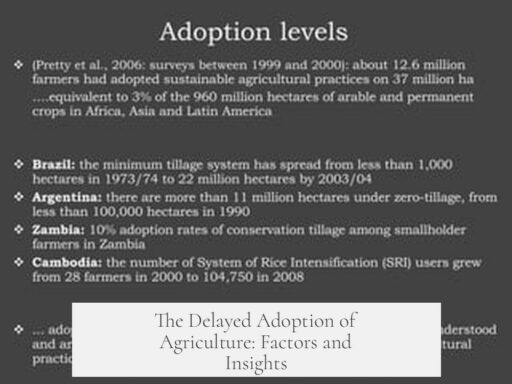

| Factor | Impact on Agricultural Adoption |

|---|---|

| Hunter-Gatherer Diet Quality | High nutrition delayed need for farming |

| Ecological Knowledge | Allowed wild resource management without farming |

| Proto-Agriculture | Gradual plant cultivation without settlement |

| Technological Skills | Limited tool-making slowed farming development |

| Environmental Changes | Triggered shift toward intensive agriculture |

In summary, farming was not delayed out of ignorance or laziness. It was a choice rooted in practicality given abundant wild resources, existing knowledge, and limited technology. The gradual adoption of proto-agriculture reflects early humans’ adaptation and long-term experimentation with managing plants. Only when pressures increased did full-scale agriculture become essential.

- Hunter-gatherers delayed agriculture due to better nutrition and less labor.

- They possessed sophisticated plant management skills protecting wild resources.

- Transition to farming was a slow, multi-generational process involving proto-agriculture.

- Technological constraints limited early farming tool production.

- Environmental shifts made farming necessary, prompting full adoption.

Why Did It Take So Long for Agriculture to Be Implemented?

Short answer: It took so long because agriculture was less appealing than the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, grew gradually from early plant management practices, and required a ton of accumulated knowledge plus reliable technology that took many generations to develop. Now, let’s unpack this fascinating historical mystery with a sharp eye and maybe a wink.

At first glance, the shift from gathering wild berries and hunting game to planting seeds and tending fields seems like an obvious step forward. But it wasn’t. Archaeological records and ethnographic studies consistently show hunter-gatherers were often taller, healthier, and had more leisure time than early farmers. Yes, you read that right—farmers worked harder and didn’t necessarily eat better.

So why would anyone willingly pick up farming? The answer starts with how people viewed agriculture—as a last resort rather than an ambition. Hunter-gatherers thrived by deeply understanding their environment. They knew how plants grew, how to encourage certain wild plants, and even managed landscapes by controlled burning or selective harvesting to increase food yields. They moved with the seasons, following rich food resources, and had no immediate reason to ditch that freedom for the grueling grind of crop cultivation.

This knowledge complicates the outdated stereotype of “primitive” hunter-gatherers who stumbled blindly into farming. Anthropologists have long abandoned that term for a good reason—these communities were sophisticated in their expertise and survival strategies. They did not experience some sudden “lightbulb moment” when they decided to domesticate plants. Instead, those decisions emerged from slow adaptation amid environmental changes, especially post-glacial shifts that altered ecosystems and resource availability.

Farming might actually be described as a “step in the wrong direction.” It was necessary but came with tradeoffs: more labor, lower nutritional quality, and less free time. So rather than a logical advancement, it was often a reluctant coping strategy when circumstances demanded it. Given that, it’s no surprise the transition wasn’t overnight.

Proto-Agriculture: The Slow Start

Before full-blown farming, a proto-agriculture phase existed. Imagine people planting seeds and then moving on, returning later to harvest the naturally grown plants. They didn’t settle or guard those crops. This gradual experimentation helped early humans learn the plant growth cycle without fully committing to agriculture.

Hunter-gatherers also tinkered with land management techniques—burning off unwanted foliage, weeding wild plants, re-planting partially harvested plants like yams, and even irrigation in some cases. Each of these small steps increased their understanding of cultivation methods bit by bit. This slow accumulation of knowledge stretched over hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.

It’s like learning to bake a cake by testing various ingredients over many decades—except their cake was survival itself and their oven was the wild terrain.

The Role of Technology and Tools

Transitioning from gathering to farming wasn’t just about knowledge—it required tools. And not just any tools, but effective farming implements. One simple example is the hoe. Here’s a fun challenge: How does your average ancient person create a hoe blade without modern tools like forges, saws, or drills? Without metalworking technology or reliable carpentry equipment, creating durable, effective tools took trial, error, and generations.

Technology and tool-making capabilities limited what early humans could achieve. The complexity of farming—from tilling soil to planting, irrigating, and harvesting—depended on technologies that took ages to develop. This technological bottleneck stretched the timeframe considerably.

With no one snapping fingers to wave magic farming wands, long generational efforts were essential to invent, refine, and pass down these technologies. Thus, the advent of agriculture reflects not just a cultural shift but a technological evolution.

Lessons and Takeaways for Today

The story of agriculture’s slow rise is a reminder that human progress rarely follows a straight line. Sophisticated behaviors don’t always look like “advancement,” and what’s “better” isn’t always about more work or novelty but sustainability and quality of life.

- Consider the balance: Hunter-gatherers enjoyed more leisure and better nutrition, but they depended on unfettered access to rich ecosystems.

- Adaptation matters: Agriculture arose not because it was better but because changing environments pressured groups to innovate survival strategies.

- Time is key: Complex systems like agriculture don’t appear overnight—they mature from countless small experiments and inventions.

Ultimately, agriculture took so long to implement because early humans were anything but primitive dabblers. They were intelligent, adaptive stewards balancing risk, reward, and the pleasures of life. Agriculture came when the dirt demanded it—and it demanded quite a bit of work.

Next time you bite into a crunchy apple or savor a freshly baked loaf, spare a thought for the millennia of trial, error, toil, and knowledge that shaped the roots of the food on your plate. Surely, that patience and persistence is something worth celebrating in our fast-paced world!

Why did hunter-gatherers delay adopting agriculture despite knowing about plants?

Hunter-gatherers had better diets and more leisure than early farmers. They managed their environment well and preferred their lifestyle. Agriculture was labor-intensive with lower yields, so it was adopted only when necessary.

How did proto-agriculture contribute to the eventual rise of farming?

Proto-agriculture involved early people planting seeds and managing wild plants without settling. These practices improved plant growth over centuries, gradually building the knowledge needed for full-scale farming.

What technological challenges slowed the development of agriculture?

Early humans lacked farming tools like hoes and the technology to make them. Creating effective tools required many generations to develop necessary skills and materials, delaying widespread agriculture.

Was the shift from hunting-gathering to farming sudden?

No. It was a slow, gradual process taking thousands of years. People experimented with plant cultivation while still maintaining nomadic habits before fully settling into agriculture.

Did ancient people lack knowledge about plant growth?

No, they understood plants and their cycles well. Hunter-gatherers practiced land management and assisted growth long before formal farming began.