Hernán Cortés destroyed Tenochtitlan and built México City on top of it primarily for military, religious, and symbolic reasons tied to conquest, control, and cultural replacement. Initially, the Spanish admired the city’s grandeur but changed attitudes after the violent conflicts during the conquest. The destruction facilitated Spanish domination while fulfilling religious and political goals.

At first, Cortés praised Tenochtitlan. It was a vast city of about 250,000 people, built on Lake Texcoco, featuring massive markets and an extensive canal system. However, after the Noche Triste—when the Spanish suffered a severe defeat retreating from the city—their respect turned into hostility. The lake’s water defenses and removable bridges made the city a fortress. The Mexica used canals to transport warriors in canoes that slowed and trapped the Spanish, who became easy targets.

The Spanish exploited their knowledge of the city’s infrastructure for a siege about a year later. They broke canals and dikes, cutting off water supplies and isolating the city. This dismantling destroyed key protections and eventually led to the city’s fall. The destruction of dikes caused problems like flooding that lasted centuries afterward because locals lost the knowledge to repair them.

Cortés’s siege strategy extended beyond the military objective. He built alliances with native groups like the Tlaxcalans, who actively sought revenge against the Mexica. This alliance brutalized the remaining defenders, both as punishment and to suppress further rebellion. The harsh tactics reflected European siege warfare norms, using exemplary destruction to intimidate others in the region.

Religious motives deeply influenced the destruction and rebuilding process. The Aztec temples and palaces represented not only political power but also native religion. Cortés and his men destroyed these structures, symbolically dismantling the indigenous faith. Following conquest, major Mexica temples and the royal palace were razed, their foundations still visible today, replaced by Spanish colonial buildings and Christian churches.

The arrival of religious orders such as the Franciscans accelerated the destruction of native religious symbols like statues, manuscripts, and art. They aimed to erase polytheistic worship and promote Christianity. This practice followed Iberian precedent, echoing traditions from the Reconquista, where Christian buildings were erected over Islamic sites to symbolize conquest and religious supremacy.

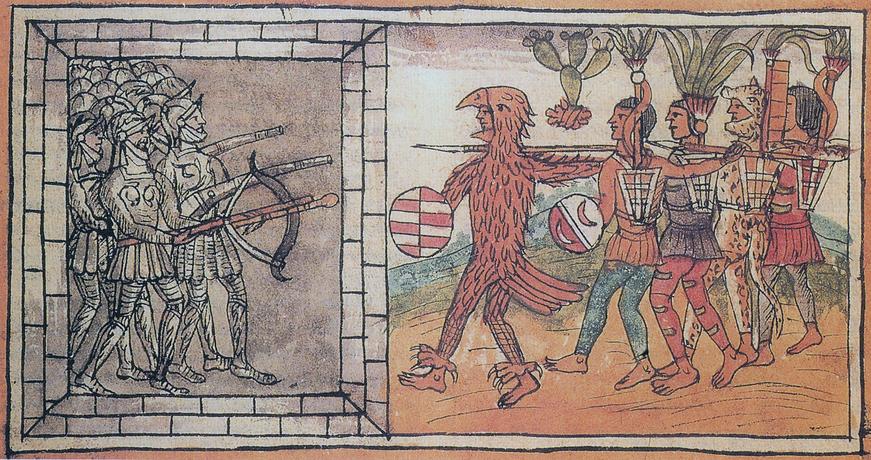

Despite this profound destruction, the narrative of total ruin is too simplistic. Cortés initially considered abandoning Tenochtitlan for Coyoacan. Instead, he allowed about 100,000 surviving natives to remain and rebuild their lives within the city. The central area was reconstructed according to European urban planning, but many neighborhoods preserved indigenous layouts, customs, and governance.

Indigenous influence persisted strongly in the colonial city. Markets essential to native commerce reopened. Four indigenous neighborhoods, aligned to the cardinal directions as before, remained alive around the new center. Native officials continued roles in local governance, including governors of Mexica descent ruling until the mid-1500s. Agricultural practices on the lake’s outskirts also survived colonial changes.

The indigenous name “Mexico Tenochtitlan” endured among native elites well into the seventeenth century, even as “Mexico City” became the Spanish term. This illustrates a cultural hybridity rather than erasure. Today, reminders of indigenous heritage appear throughout Mexico City, such as metro stations named after pre-Hispanic sites and leaders.

This blending implies that the fall of Tenochtitlan was not a clean break but a transformation. Indigenous culture adapted and persisted despite colonial conquest, creating a new, hybrid identity. Spanish goals included domination and conversion, but native peoples shaped the city’s evolution post-conquest.

| Reason | Details |

|---|---|

| Military | Destruction of defenses, cutting water; siege to capture city after Noche Triste; strategic alliances with native groups; exemplary punishment to prevent rebellion. |

| Religious | Destroy native temples and symbols; replace with Christian churches; motivated by conquest’s spiritual mission and Iberian traditions of building over conquered sites. |

| Symbolic | Replace native centers of power with colonial government buildings; erase indigenous political and religious authority; assert Spanish dominance. |

| Indigenous Survival | Natives allowed to return; neighborhoods and markets revived; indigenous officials remain; cultural hybridity develops over time. |

- Tenochtitlan was destroyed to break military resistance and weaken the Aztec empire.

- Religious destruction aimed to suppress native beliefs and insert Christianity.

- Rebuilding the city on the same site asserted Spanish power symbolically and practically.

- Indigenous people adapted and maintained cultural presence even after conquest.

Why did Hernán Cortés destroy Tenochtitlan and build México City right on top of it?

Hernán Cortés destroyed Tenochtitlan and built México City on its ruins to conquer and control the powerful Mexica empire, erase native religious symbols, and establish Spanish colonial authority directly at the heart of the former capital. But there’s more to this story than just a brutal military victory. Let’s unravel the layers—military, religious, and cultural—that drove this historic transformation.

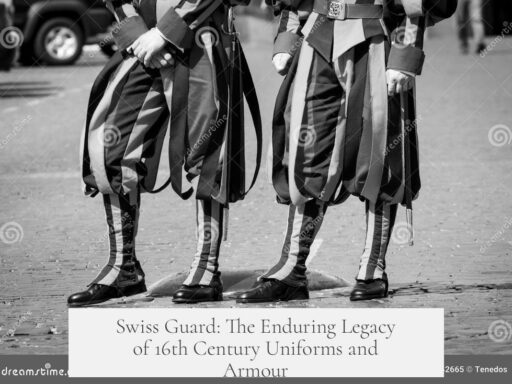

Imagine arriving in a vast city dazzling enough to stun the Spanish conquistadors. Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, sits on an island in Lake Tezcoco. Its population reaches an estimated 250,000 people—huge by 16th-century standards—with a vibrant market system and canals that weave through it like veins. Early Spanish reports reveal genuine admiration for this architectural marvel and urban planning feat.

So why the sudden change from awe to destruction?

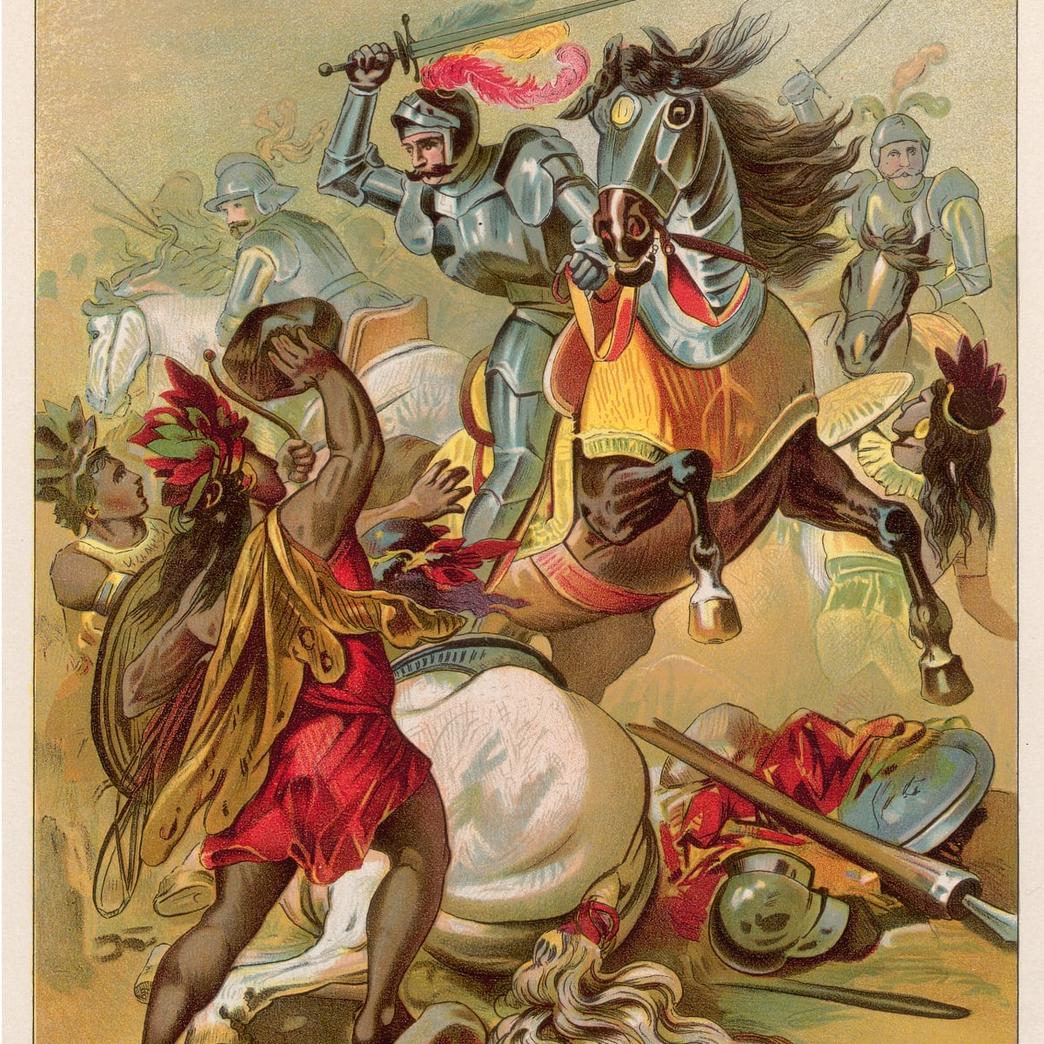

Military Reasons: From Admiration to Siege Warfare

Initially, Cortés and his conquistadores admire Tenochtitlan. The city’s canals and bridges impress them, but after the infamous Noche Triste—“Sad Night”—their tone shifts dramatically. During this brutal Mexican counterattack, many Spaniards are killed or drowned as they try to flee through the city’s water channels. The Mexica warriors exploit their home terrain expertly, turning urban waterways into battle lanes filled with armed canoes. This natural fortress frustrates the invaders and costs them dearly.

Barbara Mundy sheds light on this crucial turning point:

“The surrounding lake functioned like a moat protecting the island city; bridges could be removed to isolate the capital… Spaniards found enemies using canals as transport routes for canoes with up to 60 armed warriors each. Retreats along narrow causeways put them in firing lines for Mexica archers.”

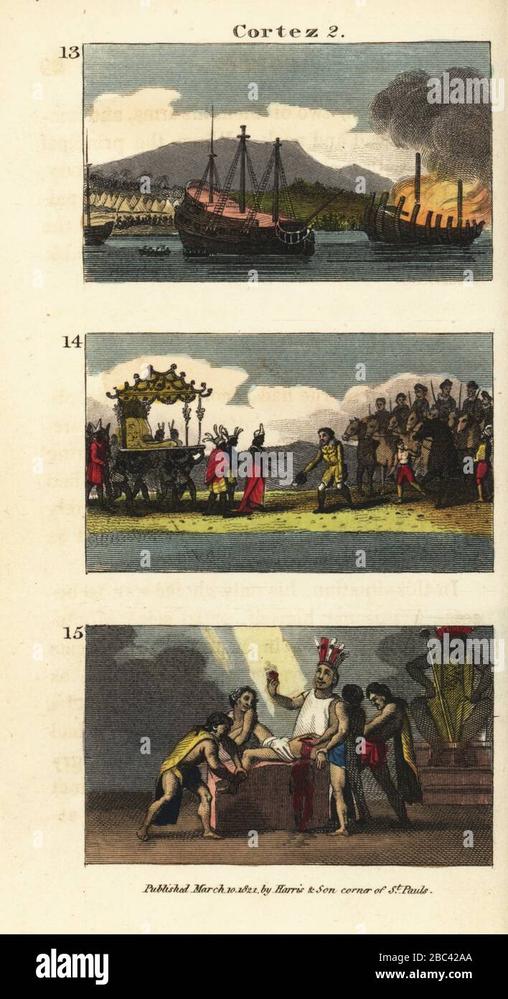

This military challenge forced Cortés to rethink his strategy. He spends the year between Noche Triste and the siege forging alliances with rival indigenous groups like Tlaxcala and Tezcoco. With these allies, Cortés uses knowledge of the city’s dikes and canals to cut off supplies and weaken defenses, especially by destroying the dikes that protected Tenochtitlan from floods and maintained fresh water flow.

This destruction had long-term effects: the area would suffer severe flooding for centuries after, due to the loss of these protective engineering feats. Siege warfare wasn’t just about immediate conquest; it was about breaking the enemy’s infrastructure and willpower.

This brutal military tactic also served as a grim example to other native groups. The harsh treatment of the Mexica was a warning: resist, and face total destruction. Cortés’ allies, especially the Tlaxcalans, took revenge on the Mexica as part of the political reshuffling, ensuring the Spanish success was backed by local powers.

Religious Motives: Erasing the Old to Make Way for the New

Conquest wasn’t just about land and power. Spain’s official reason for expansion into the Americas was to bring Christianity to indigenous peoples. This zeal meant systematically destroying the religious heart of the Mexica.

Once the city fell, Aztec temples and the royal palace faced targeted demolition. The Spaniards demolished the giant temples where Mexica priests offered human sacrifices—a practice Cortés and his men found deeply abhorrent. While the Spanish admired the city’s physical layout, they despised any symbols tied to the native religion.

The Franciscans, invited early by Cortés to evangelize, eagerly destroyed statues, codices, art, and sacred sites. This wasn’t unique to Tenochtitlan; similar religious cleansing happened across Central Mexico.

Following a familiar Iberian tradition from their own reconquista centuries earlier, the Spanish built Christian cathedrals and colonial palaces right over Mexica sacred sites. Symbolically, this replaced native religious and political power with Spanish rule and Christian belief.

Aftermath: Not Just Destruction but Transformation

The simple story of total destruction misses nuances. Cortés initially considered abandoning the island in favor of Coyoacan, but ultimately allowed thousands of natives to return and rebuild. While the city center was redesigned in classical European style—straight streets, plazas, churches—surrounding neighborhoods still maintained indigenous practices and architecture.

Markets that fueled native economies reopened quickly. Indigenous governance didn’t vanish overnight: Mexica-descended governors continued until 1560. Even the city’s name was debated. Indigenous elites kept calling it “Mexico Tenochtitlan,” acknowledging their heritage despite Spanish insistence on “Mexico City.”

Today, Mexico City’s metro station names and public art honor pre-Hispanic places and leaders, showing indigenous influence persists centuries later. The conquest ended an empire but also launched a new, hybrid culture blending European and native elements under colonial rule.

So, Why Destroy and Rebuild on Top?

Cortés’ destruction of Tenochtitlan was a strategic cocktail of military necessity, political symbolism, and religious transformation:

- Military Control: Destroying defenses and infrastructure prevented uprisings and secured Spanish dominance.

- Political Demonstration: It sent a clear message to indigenous rivals: Spanish conquest was absolute and irreversible.

- Religious Conversion: Eliminating native temples erased idols and beliefs that Spanish missionaries wanted to replace.

- Symbolic Replacement: Building México City atop the ruins literally and figuratively established colonial power where Aztec rulers once stood.

The transition wasn’t clean or complete—indigenous people shaped the new city’s economy and culture for centuries. By understanding these overlapping motives and consequences, we see why Cortés didn’t simply destroy Tenochtitlan and move on. Instead, the conquest and reconstruction created a new capital that bridges Aztec history and colonial legacy.

References and Further Reading

- Barbara Mundy, Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City.

- Fernando de Alva Ixtlixlochitl, native chronicler on Tlaxcalan actions.

- Earliest European map of Tenochtitlan (1524)

- Discussions on indigenous continuity in Mexico City on Reddit’s AskHistorians.