Congress quickly voted for presidential term limits after Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) died because the Republican-controlled Congress aimed to prevent extended executive power and secure the balance of power in government. Despite FDR’s popularity and multiple re-elections, concerns about unchecked presidential authority, fears of totalitarianism, and partisan opposition formed the basis for the 22nd Amendment.

FDR’s unprecedented four-term presidency broke with the long-standing two-term tradition established by George Washington. His death on April 12, 1945, led to Harry Truman assuming the presidency amid significant political shifts. Truman initially enjoyed strong approval, but postwar economic challenges damaged his reputation. Inflation surged and a wave of labor strikes rocked the nation, which made Truman politically vulnerable.

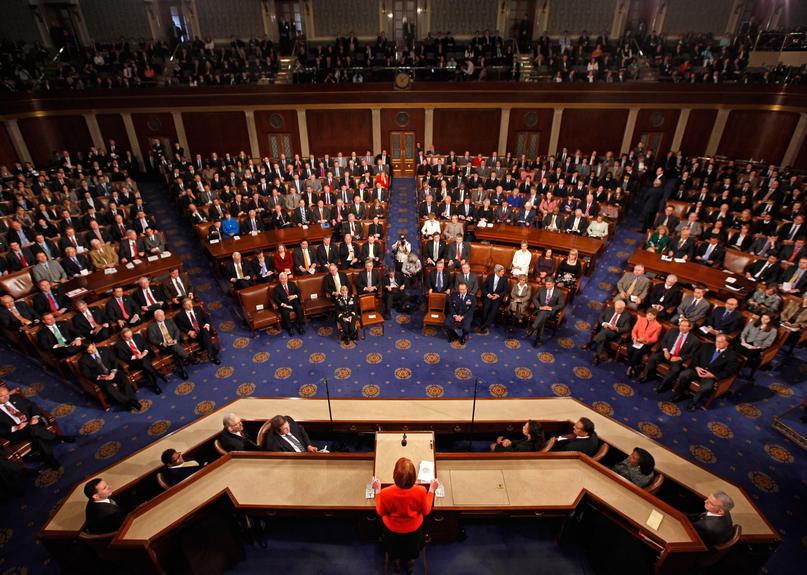

In the November 1946 midterms, Republicans seized the moment. They won control of both the House and the Senate for the first time since 1932. Many Republicans opposed Roosevelt’s extended tenure. They campaigned strongly for term limits. On January 3, 1947, Republican Representative Earl C. Michener introduced House Joint Resolution 27 (HJR27), which later became the 22nd Amendment.

- The resolution aimed to submit presidential term limits to the American people, codifying the customary two-term limit.

- Republicans saw this as a necessary step to settle long-standing debates about executive tenure permanently.

- They feared a lengthy presidency could lead to totalitarianism by concentrating too much power in the executive branch.

- This could weaken Congress and undermine the checks and balances central to the U.S. Constitution.

The political support for the amendment largely followed party lines. No Republicans opposed it, but three-quarters of Democrats voted against it. Out of 285 yeas, only 47 were Democrats. The opposition argued that the public already controlled presidential terms via elections and that imposing limits restricted democratic choice. The people had twice approved FDR for more than two terms in 1940 and 1944, signaling there was no widespread public demand for term limits at that time.

Democrats accused Republicans of pushing a partisan agenda, citing limited public correspondence on the issue. They contended that term limits would transfer electoral decisions from voters to politicians and state legislatures, reducing democracy rather than protecting it.

Some opponents warned that limiting terms could backfire during crises. For instance, in a national emergency, denying trusted leadership might trigger extra-constitutional actions, ironically risking dictatorship—the very outcome term limits sought to prevent.

Historical context shows term limits were debated since the nation’s founding. Between 1789 and 1947, over 270 resolutions addressed limits on presidential re-election, a debate intensified during FDR’s long presidency.

| Aspect | Republican Argument | Democratic Argument |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for Amendment | Prevent extended terms, totalitarian risk, preserve checks and balances | Voters decide presidential terms; no evident public demand for limits |

| Effect on Democracy | Resolve debate; protect government system | Restricts voter choice; undermines democracy |

| Timing | Post-1946 Republican victory; 18 months after FDR’s death | Too sudden, politically motivated |

| Public Opinion | Poorly expressed but needed formal resolution | Minimal public pressure for change |

The amendment reflected congressional concerns about preserving constitutional balance and preventing the emergence of overly dominant presidents. Republicans capitalized on party control and midterm successes to push through the change.

In sum, Congress quickly voted for term limits despite FDR’s popularity because of persistent fears that unchecked executive power could harm democratic governance. The 22nd Amendment emerged amid partisan tensions, with Republicans advancing the idea to enshrine limits, while many Democrats viewed it as an unnecessary restriction on voter freedom.

- FDR’s four terms broke tradition, raising concerns about executive power.

- Postwar political shifts gave Republicans control to act on term limits.

- Republicans saw limits as essential to prevent dictatorship and protect legislative power.

- Democrats feared limits would restrict democratic choice and lacked public support.

- The 22nd Amendment codified a two-term limit following these debates.

Why Did Congress Quickly Vote for Presidential Term Limits After FDR’s Death?

Congress moved swiftly to impose presidential term limits after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death, despite his popular extended presidency, because of deep partisan tensions, fears of executive overreach, and a desire to formally settle ongoing debates about presidential tenure. Let’s unpack this political drama that shaped U.S. constitutional history.

The story starts on April 12, 1945. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had been president across an unprecedented four terms, passed away. He was succeeded by his vice president, Harry Truman, who stepped into both a powerful position and a tough act to follow. Truman did well at first, enjoying high approval as World War II ended. Yet, the post-war shift wasn’t easy. Inflation soared, and the largest strike wave in American history tested his leadership. His failure to effectively manage this turmoil tanked his popularity by 1946. Here was the context: unrest at home and changing political winds.

The Political Swing in 1946 Midterms

November 1946 was a turning point. Republicans won a sweeping victory in the midterm elections. They seized control of both the House and Senate—a gain they hadn’t made since 1932. This shift gave Republicans leverage to act on a long-standing issue: presidential term limits.

See, though Roosevelt had broken the traditional two-term rule by winning four elections, imposing term limits wasn’t new. The Founders had debated this in the 18th century, and between 1789 and 1947, no less than 270 attempts surfaced in Congress to formally limit a president’s terms. The topic resurfaced sharply during FDR’s presidency, making it politically charged. Republicans, many of whom had opposed Roosevelt vehemently, finally had the votes to press the issue.

Why So Quick? Not Immediately After FDR Died

Contrary to popular belief, Congress didn’t rush this decision right after Roosevelt’s death. They waited over a year. The Republicans seized the moment only after their substantial midterm gains gave them the power to push for the constitutional amendment.

On January 3, 1947, Republican Representative Earl C. Michener proposed House Joint Resolution 27 (HJR27). This resolution would eventually become the 22nd Amendment, formally limiting presidents to two terms or a maximum of 10 years in office.

The Partisan Battle Lines

Support for term limits wasn’t bipartisan harmony. It was a partisan war. Not a single Republican voted against the amendment, but approximately 75% of Democrats opposed it. The final House vote was 285-121 with 26 abstentions. Among those who approved, only 47 were Democrats; in other words, the Republican ranks were nearly unanimous.

Why the fierce split? Because Democrats argued the amendment was unnecessary interference with the democratic process. After all, they pointed out, the American people already had control—they could vote out presidents at the ballot box every four years. Plus, two of Roosevelt’s four terms had come after the public deliberately voted for him, proving some willingness to break tradition without worry.

Republican Case: Protecting Democracy by Limiting Power

Republican supporters claimed term limits would end endless debates about presidential tenure. Here’s a direct quote from the era:

“By reason of the lack of a positive expression upon the subject of tenure… much public discussion has resulted… It’s the purpose of this legislation… to submit this question to the people… and thereby set at rest this question.”

They insisted this was no political ploy. Term limits were meant to protect the republic from the risks of concentrated executive power turning into a form of totalitarianism. Longer presidencies, they argued, made it easier for a president to bully the legislature and judiciary. The separation of powers and checks and balances could erode, leaving all branches subservient to an all-powerful executive.

Further, term limits would foster legislative primacy by keeping fresh leadership options open for the nation. It prevented one person’s dominance from stifling political competition and potential new leaders.

Democratic Resistance: Trusting the Voters

Democrats took a very different angle. Why hand a political minority in Congress the power to limit democracy? The people already ruled every four years through elections. Why muddy that water with a permanent constitutional limit?

One Democratic argument was strikingly frank:

“By this amendment, we say quite frankly that the people have not sufficient intelligence or judgment to know their own minds… and, as a result, we must… place them in a strait-jacket.”

They believed restricting the voters’ ability to choose a popular president was undemocratic. After all, Americans had twice chosen to break the two-term tradition by re-electing Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944. Restricting terms, therefore, clamped down on a fundamental democratic right.

Interestingly, many Democrats argued the amendment lacked public support. One lawmaker mentioned receiving only “eight pieces of mail” about the topic around the country. It appeared the issue was driven by partisan officials rather than loud public demand.

On top of that, some feared the amendment might have the opposite effect and even increase the risk of totalitarianism. If a crisis like an atomic emergency occurred, limiting presidential terms could force the public into extra-constitutional actions if they mistrusted new leadership, ironically paving the path to dictatorship.

How This Changed American Politics

The 22nd Amendment passed in 1947 and was ratified by the states in 1951. It officially barred any president from serving more than two terms. This formalized the informal two-term tradition set by George Washington. Yet it did so amid contentious debate about democracy, power, and trust.

The amendment shaped future presidencies. Dwight Eisenhower and every president since has been limited by this rule. While popular presidents can still serve two terms, they face a firm constitutional cap, ensuring no one dominates the political stage indefinitely as Roosevelt once did.

A Unique Historical Moment

Why did Congress act now despite FDR’s popularity? Because the Republicans finally held power and saw an opportunity. They framed term limits as a guardrail against tyranny and excessive executive power. Meanwhile, Democrats defended voter freedom and warned about unintended risks.

This clash captured a core tension in American democracy: the balance between limiting power and preserving choice.

What Can Today’s Readers Learn from This?

- Political Timing Matters: The 22nd Amendment wasn’t a spontaneous decision but a calculated move seizing political opportunity after a shift in power.

- Checks and Balances Are Vital: The amendment reflects fears that long-term presidencies can disrupt the delicate relations among government branches.

- Democracy Is Complex: Limiting a leader’s terms can both protect democracy and be criticized as limiting the people’s voice.

- Public Support Is Crucial: The debate showed the gap between political elites’ priorities and general public engagement.

In today’s polarized world, the story reminds us to examine carefully who benefits from term limits and what risks we accept by imposing them.

Final Thought: Do Term Limits Still Make Sense?

Would Roosevelt have been re-elected if term limits didn’t exist? Possibly. Would a fifth term be a healthy choice for democracy? The 22nd Amendment says no, to avoid concentrating too much power in one person’s hands. But as history shows, this choice is never simple or unanimous.

So next time someone wonders why our presidents are barred from serving more than two terms despite some being popular longer, remember: it’s less about a single leader, and more about protecting the system from long-term dominance and ensuring a healthy political rotation.

Why did Congress pass presidential term limits after FDR’s death despite his popularity?

Congress wanted to prevent any president from accumulating too much power. Republicans, who gained control in 1946, feared long terms could lead to totalitarianism and weaken Congress’s authority.

Was the push for term limits immediate after FDR died?

No, the 22nd Amendment proposal came 18 months after FDR’s death. Republicans took advantage of their 1946 election victory to push the measure forward.

Did everyone in Congress support the 22nd Amendment equally?

No, support was largely partisan. Almost all Republicans voted for it. Most Democrats opposed it, arguing it restricted the people’s right to choose their president freely.

Why did some Democrats oppose presidential term limits?

They believed voters should decide how many terms a president serves. Since FDR was elected four times, many saw term limits as limiting democracy and shifting power from people to politicians.

Had term limits been discussed before FDR’s presidency?

Yes. From 1789 to 1947, about 270 proposals on presidential term limits were introduced. The issue gained urgency during and after FDR’s four terms in office.