The British decided to give India independence due to a complex mix of post-World War II challenges, rising Indian nationalism, the growth of the freedom movement, and administrative difficulties in maintaining control over a vast and diverse population. These factors built over decades and culminated in 1947 with the transfer of power, ending nearly two centuries of British rule.

After World War II, Britain was economically and logistically strained. The war effort drained British resources and exposed the limits of imperial governance. Maintaining control over India, which had a dynamic and rapidly growing population, became increasingly impractical. This exhaustion hastened an outcome that might have been inevitable within the following decade. The sheer size and complexity of India’s population, combined with Britain’s diminishing global power, made continued rule unsustainable.

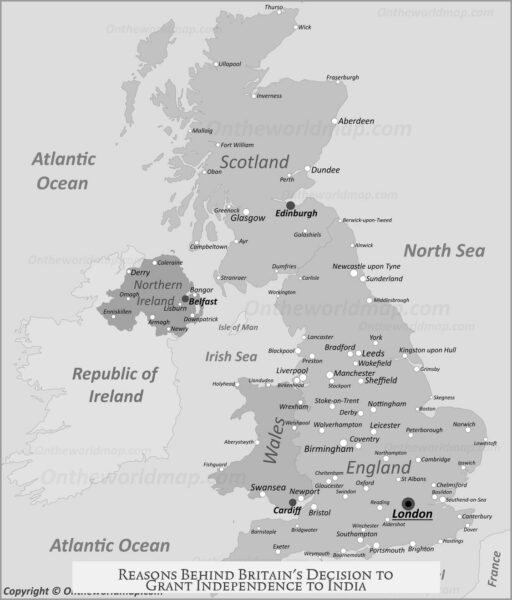

Politically and socially, India was not a united country before independence. It was fragmented into numerous princely states, many of which had longstanding rivalries. British colonial policy initially exploited these divisions, using a “divide and rule” strategy by pitting princely states against each other to maintain power. Over time, however, this tactic backfired. As the British favored certain states and later betrayed them, a gradual and unintended unity among the diverse regions formed under British control. This unity was symbolized by the spread of the English language, which became a common medium of communication across a land with more than 100 languages and dialects. This unintended cohesion contributed to a growing Indian identity and heightened discontent with colonial rule.

The freedom movement also played a critical role in pushing Britain toward independence. While often viewed as the sole driver of independence, the freedom movement must be understood in the broader context of geopolitical and social realities. The Indian National Congress (INC), founded in 1885, originally sought greater Indian participation in governance but evolved, especially under Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership, into a powerful nationalist force demanding self-rule. Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violent resistance inspired wide segments of the Indian population to unite in opposition to colonial rule.

Nationalism was challenging to foster in India’s highly diverse society consisting of multiple languages, religions, and ethnic groups. Historian Ramachandra Guha describes India as an “unnatural nation,” given the absence of common racial, linguistic, or religious ties uniting its people. Nonetheless, the freedom movement succeeded in instilling a sense of national unity through the idea of “Us vs. Them”—Indians united against British imperialism. Movements like the 1942 Quit India campaign exemplified this push, although initial efforts faced limitations due to lack of coordination and British repression.

The two World Wars significantly influenced British policy toward India. India contributed millions of soldiers to the British war efforts in both conflicts, which fueled Indian demands for self-governance. The British responded with political reforms such as the Government of India Acts that offered limited power-sharing but failed to satisfy nationalist aspirations.

Following World War II, the economic exhaustion of Britain and limited political will at home made the prospect of managing India’s vast administration untenable. The Labour government that came to power after 1945 recognized that controlling India required resources and support it no longer had. The situation was further complicated by the communal tensions between Hindus and Muslims, leading Britain to decide on a partition of India into two states—India and Pakistan—based primarily on religious majorities. This decision aimed to ease Britain’s withdrawal but resulted in widespread violence and displacement.

Despite granting independence, Britain did not sever all ties abruptly. Post-independence, British officials like Lord Mountbatten assisted with integrating princely states into the new nations, working alongside Indian leaders like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The British also left behind infrastructure, legal institutions, railways, educational systems, and a political framework that shaped modern India.

| Factors Leading to British Decision | Details |

|---|---|

| Post-WWII Exhaustion | Logistical and financial inability to manage empire after war; Britain’s diminished global power. |

| Unintended Indian Unity | British ‘divide and rule’ policies unintentionally fostered pan-Indian identity through English language and political developments. |

| Freedom Movement | Nationalist agitation, led by Indian National Congress and Gandhi’s non-violent resistance, galvanized public opinion for independence. |

| Communal Tensions and Partition | Religious divisions prompted Britain to partition India and Pakistan for a quicker, less risky exit. |

| Continued British Involvement | British aided integration of princely states and left institutional legacies post-independence. |

“India gained independence from the United Kingdom on August 15, 1947, marking the end of nearly two centuries of British colonial rule.”

- World War II severely weakened Britain’s ability to govern India.

- British policies unintentionally unified India politically and culturally.

- The freedom movement fostered Indian nationalism despite diverse communities.

- Partition was a British strategy to exit while managing religious conflict.

- Post-independence, Britain remained involved in state integration and institution-building.