Feudal Japan could field such large armies mainly due to its economic and administrative system tied to land productivity rather than mobilizing a higher percentage of its population compared to European countries. The capacity to raise vast forces depended heavily on the koku system, which quantified land productivity and linked it directly to military recruitment. This system allowed daimyo to mobilize troops proportional to the rice yield of their domains, making efficient and scalable military organization possible.

During the late Sengoku period, daimyo typically deployed between 30 to 50 men per 1,000 koku of assessed land productivity. Few exceeded 60 men per 1,000 koku. This ratio is critical to understanding the army sizes. For example, at the pivotal Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, the standard mobilization rate was around 30–35 men per 1,000 koku. With Japan’s land productivity totaling roughly 18.5 million koku in 1598, this system theoretically allowed for a large pool of troops aligned precisely with economic resources.

Estimates based on this arrangement yield impressive but realistic troop numbers. At an optimistic maximum of 60 men per 1,000 koku, Japan’s potential military mobilization would reach about 1.1 million men, equating to about 5.5% of a population estimated at 20 million. More conservative and probably more accurate assumptions, such as 40 men per 1,000 koku, produce figures around 740,000 troops, or 3.7% of the population. These numbers fit well with historical estimates ranging between 700,000 and 750,000 soldiers during the closing Sengoku period.

However, Japan did not mobilize a higher relative percentage of its population than European countries did. For instance:

- The Battle of Towton (1461) in England and Wales saw around 1.82% of the population mobilized.

- Swedish forces at the Battle of Lützen (1632) mobilized between 0.76% and 1.27% of their population.

- Spain’s military forces during the same era constituted approximately 2.4% to 3.6% of its population.

- The Dutch Republic mobilized about 5.1% of its population for military service.

- Denmark-Norway’s mobilization reached an exceptionally high 13.5% in 1625.

Compared to these, Japan’s 0.8% at Sekigahara and 1.25–1.5% at the Osaka campaigns fall within a plausible range, debunking notions of exceptional Japanese demographic mobilization.

Japan’s ability to field large armies thus relied not on extraordinary population mobilization rates but on an effective system correlating agricultural output to military organization. The koku measurement framework enabled a clear estimate of how many men each daimyo could muster based on the productivity of their lands.

This ensured that military recruitment reflected economic realities. Daimyo would allocate manpower proportionally to rice production, allowing for large, sustained armies without overburdening the peasantry or risking economic collapse. Such an arrangement embedded military capacity within existing bureaucratic and fiscal structures, facilitating efficient troop mobilization.

Additionally, the logistical capacity to support standing armies grew over the late Sengoku period. Centralization trends and administrative reforms under powerful leaders, especially under Tokugawa Ieyasu, improved resource management, supply lines, and coordination among daimyo, reinforcing army size capabilities.

No clear evidence suggests that feudal Japanese mobilization strategies were inherently superior or unique compared to Europe. Rather, Japan shared similar proportional military engagement patterns shaped by demographic and economic factors. Arguments for Japanese “exceptionalism” often lack support from primary sources and do not adequately account for comparable European practices.

In summary, Japan fielded large armies because:

- The koku-based system linked land productivity directly to troop recruitment.

- Daimyo mobilized a reasonable number of soldiers relative to their economic resources (30–50 men per 1,000 koku).

- Overall population mobilization percentages were comparable to or slightly less than those in Europe.

- Administrative and logistical frameworks supported sustained troop deployment.

- Military organization integrated tightly with economic output, avoiding overextension.

| Battle/Region | Estimated Troops | % of Population Mobilized |

|---|---|---|

| Sekigahara (Japan, 1600) | ~160,000 | 0.80% |

| Osaka Campaign (Japan, 1614-1615) | 250,000 – 300,000 | 1.25% – 1.50% |

| Battle of Towton (England/Wales, 1461) | ~50,000 | 1.82% |

| Swedish Army at Lützen (1632) | ~70,000 – 120,000 | 0.76% – 1.27% |

| Spain (European territories) | 300,000 | 2.4% |

- Large army sizes in feudal Japan result from economic-administrative mechanisms, not exceptional population mobilization.

- The koku system quantifies productivity for scalable and efficient troop recruitment.

- Japan’s mobilization percentages align with, or fall slightly below, various European examples.

- Logistics and governance structures support maintaining large forces.

- Claims of Japanese military exceptionalism lack strong primary source backing and should be considered cautiously.

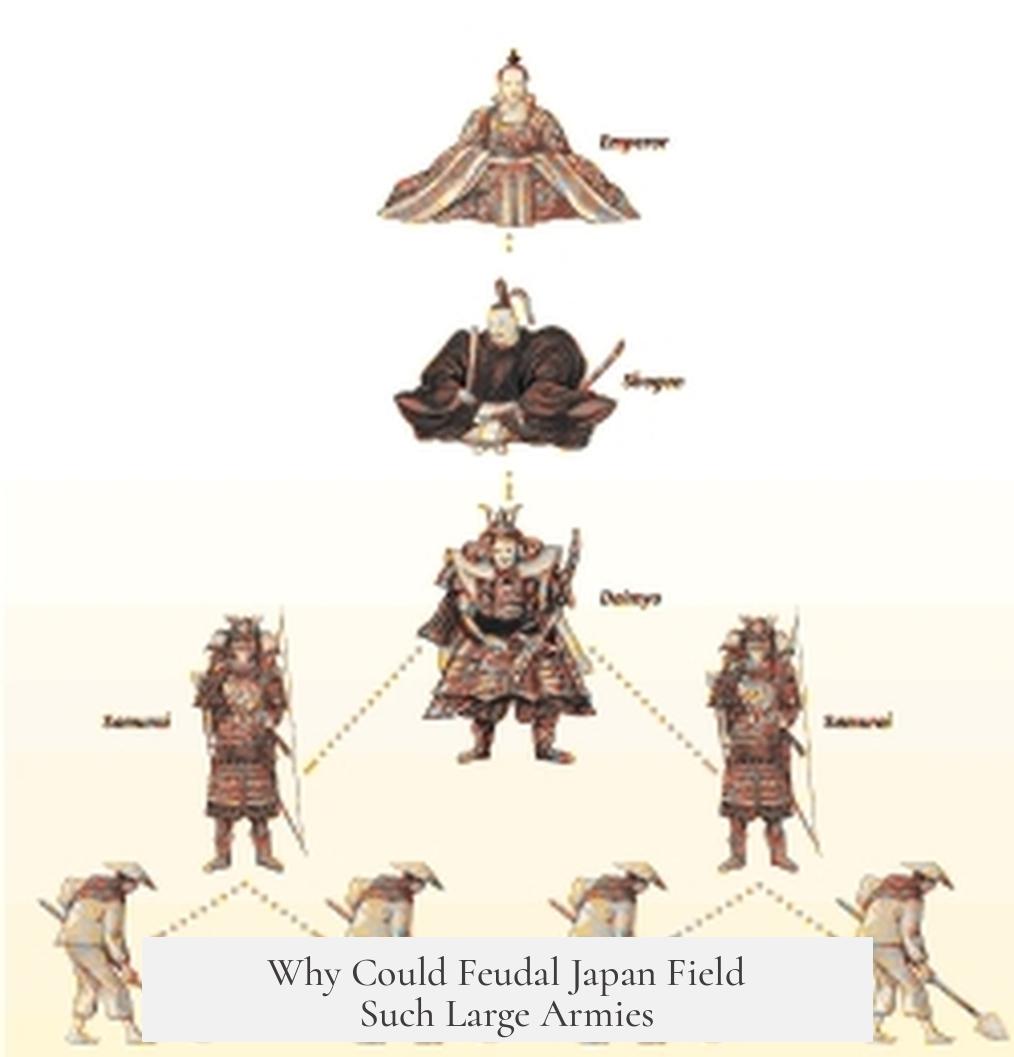

Why Could Feudal Japan Field Such Large Armies?

If you ever wonder how feudal Japan managed to assemble armies numbering in the hundreds of thousands, the answer might surprise you. Japan’s capacity to field large armies was not due to mobilizing a higher percentage of its population than European counterparts, but rather because of its highly organized economic and administrative systems, especially the koku-based land productivity assessments. Let’s unpack that fascinating blend of numbers, systems, and history.

The Population Mobilization Puzzle

The first myth to bust: feudal Japan did not conscript a larger slice of its population than European countries. For example, during the bloody Battle of Towton in 1461, England and Wales fielded about 1.82% of their population under arms. Sweden’s army at the Battle of Lützen (1632) ranged from 0.76% to 1.27% depending on the population estimate.

Japan’s numbers for legendary battles like Sekigahara (1600) and Osaka (1614-15) fall comfortably within these ranges. For Sekigahara, roughly 0.80% of Japan’s population fought; for Osaka, estimates range from 1.25% up to a maximum of 1.50%. Not quite the mass conscription story some imagine.

Japan at Sekigahara (1600): 0.80% mobilized. Japan at Osaka (1614-15): Between 1.25% and 1.50% mobilized.

This means that Japan didn’t corner the market on population army recruitment. The difference lies elsewhere.

The Koku System: A Land-Based Military Ledger

Here’s where things get interesting. The core of feudal Japan’s military might isn’t in sheer manpower percentages but in how their economy related to troop numbers. Japan measured land value and productivity in koku — roughly the amount of rice required to feed one person for a year. Each daimyo’s (feudal lord’s) domain was rated in koku, and this rating connected directly to how many troops they could field.

Late Sengoku-period daimyo typically brought between 30 and 50 men per 1,000 koku. Few pushed above 60 per 1,000 koku. At the famous Sekigahara battle, the usual number was around 30 to 35 men per 1,000 koku. This system allowed the shogunate and daimyo to estimate military capacity efficiently by measuring land productivity rather than relying on census figures alone.

This makes great practical sense. Imagine being responsible for raising an army—you don’t want to guess blindly. Your income (mainly rice production) determines your military potential, and daimyo could plan appropriations accordingly. The koku system tied economics intricately to military logistics.

Potential Numbers and Realistic Estimates

Based on detailed land surveys from 1598, Japan’s theoretical maximum troop strength could reach about 1.1 million soldiers—roughly 5.5% of the population—assuming you use the optimistic 60 men per 1,000 koku ratio.

More realistically, the figure is closer to 740,000 troops, or 3.7% of a 20 million population baseline. Historical estimates for late Sengoku armies range between 700,000 and 750,000 men. This impressive number speaks to Japan’s economic and military organization more than to simply drafting every able-bodied farmer.

So How Does This Compare to Europe?

Japan’s numbers look impressive, don’t they? But how do they stack up against contemporaries in Europe?

- Spain’s European territories fielded about 300,000 soldiers, which was 2.4% of their population.

- The Kingdom of Spain alone managed 3.6% troop mobilization.

- The Dutch Republic, fiercely independent, had around 5.1%.

- Sweden’s well-regarded army reached 6.0%.

- Denmark-Norway tops the chart with a remarkable 13.5% — a mobilization number that truly shocks modern sensibilities.

Comparatively, Japan’s 3.7% to 5.5% maximum participation does not challenge the upper spectrum of Europe. This erases notions that Japan magically summoned armies from thin air or some uniquely populous culture.

Why Then Were Japan’s Armies So Large?

The secret emphasizes not mere population numbers but the country’s economic backbone and logistics. The koku system enabled precise coordination between agricultural wealth and military potential. This balance prevents overextension and poor resource allocation, common in armies conscripting “everyone.”

Furthermore, Japan’s feudal structure—intensely hierarchical but flexible—promoted loyalty and efficient troop mobilization. Daimyo had vested interests in maintaining strong, well-equipped forces proportional to their resources. The administrative machinery tracked land productivity rigorously, which helped in budgeting soldiers without wrecking the economy.

Japan’s geographical constraints also matter. The islands limited massive invasions compared to vast continental battlefields. This meant armies needed to be functional and sustainable. Japan’s clans could pool resources during conflicts without sacrificing normal production, leading to durable military campaigns.

Turning Numbers into Actionable Insights

If you are a military enthusiast, historian, or even a strategist looking at feudal logistics, several lessons emerge:

- Systems Matter: Measuring economic output (like koku) to determine military capacity is smart. Modern forces could learn from tailored resource allocations.

- Realism Over Mythology: Don’t assume larger armies mean population frenzy. Efficient administration can achieve the same result with balanced inputs.

- Context is King: Comparing mobilization percentages without cultural and administrative context leads to errors.

Final Thoughts

Why could feudal Japan field such large armies? Simply put, it’s a tale of well-oiled economic structures meeting disciplined political will. While Japan’s percentage of population militarized compares fairly with Europe’s, its link between income and troop contributions paints a unique picture.

Think of it as a medieval version of “pay as you grow” military recruitment — the more productive your lands, the more men you can send to the field. No wizardry here, just smart management.

Could Japan have pushed even further? Possibly, but the intricate balance kept armies large enough to wage war effectively, yet not so large as to cripple the homeland. That’s feudal efficiency for you.