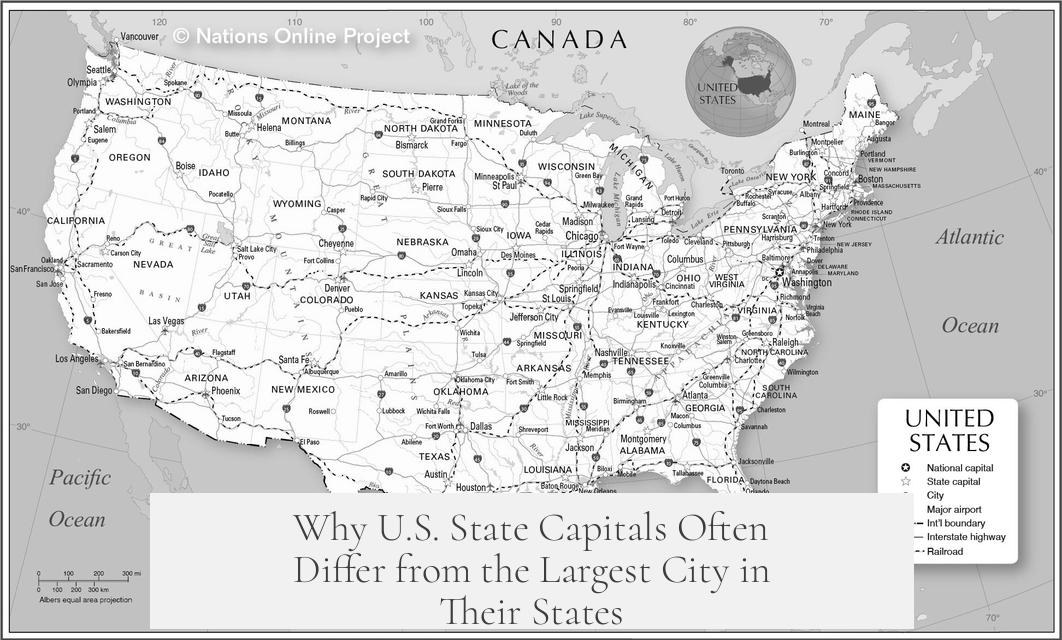

U.S. state capitals are usually not the largest city in the state because many were established before major urban growth shifted population centers. Capitals were often chosen for their central location, political neutrality, and accessibility, rather than for size or commercial power.

At the time of their founding, many capitals were the largest cities or key regional hubs. For example, Albany, New York, was among the top 10 largest U.S. cities in 1810. These cities were typically situated on important transportation routes or crossroads connecting rural and urban areas.

However, the Industrial Revolution and economic changes caused some cities to boom beyond their state capitals. Cities like Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania grew rapidly because of steel industries, while others such as Chicago, Los Angeles, and Las Vegas expanded after initial state capitals were set. These “boom” cities eventually became larger due to industrial growth, migration, and new economic opportunities.

Some states relocated their capitals after founding to serve political or geographic goals. Illinois, for instance, moved its capital twice—from Kaskaskia to Vandalia, then to Springfield—aiming for a more central and less commercially influenced location. This move reflects a common idea: government should be separate from the commercial centers thought to harbor corruption.

Many capitals were deliberately placed more centrally within their states to improve representation and accessibility for all residents. Sacramento in California was chosen for its accessibility between the gold fields and San Francisco. Jackson, Mississippi, was selected for its position near the state’s geographic center, a strategy reflecting the state’s population distribution at the time. Oklahoma City illustrates the same principle.

In contrast, the largest cities tend to be port or coastal cities, such as New York City, Miami, or San Francisco. These locations, while economically powerful, are often peripheral within their states. Their position on a coastline or major waterway makes them less suitable as statewide political capitals, which require a more equitable geographic position.

Capitals were also chosen for their function as transportation hubs and points of logistical accessibility. Sacramento, while smaller than nearby San Francisco in the mid-1800s, was better positioned for governance because it sat on navigable waterways and was midway between key economic areas. This made the capital an effective meeting point for government officials and citizens from all parts of the state.

The choice to separate capitals from large commercial centers was often motivated by a desire to reduce the influence of business interests on politics. A smaller or more centrally located city was less likely to be dominated by the economic elite, helping to ensure more balanced governance across diverse regions.

| Factor | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Historical size | Capitals were often the largest cities when founded. | Albany, NY in 1810. |

| Economic shifts | Industrial growth caused other cities to outgrow capitals. | Pittsburgh, PA; Chicago, IL. |

| Relocation for politics | Capitals moved to reduce corruption and centralize. | Illinois capital moved to Springfield. |

| Central location | Capitals placed to represent entire state population. | Jackson, MS; Oklahoma City, OK. |

| Port city drawbacks | Largest cities often coastal, not central. | New York City, San Francisco. |

| Transportation accessibility | Capitals selected for easier access statewide. | Sacramento, CA. |

The reasons for capitals being smaller than the largest cities stem from a mix of history, economics, geography, and politics. Capitals were initially the largest cities or key hubs. Over time, booming industries and migration shifted populations to other cities. Political leaders often sought to avoid centralized economic power by locating capitals in less commercially dominant or more central spots. Accessibility and political balance frequently guided location decisions.

- Most state capitals were once the largest or centrally located cities at founding.

- Industrial growth created bigger cities outside capitals.

- Capitals often moved to politically neutral, central locations.

- Large cities tend to be coastal ports and not geographically central.

- Transportation access influenced capital placement.

- Separating government from commercial centers aimed to reduce corruption.

Why Are U.S. State Capitals Usually Not the Largest City in the State?

This question often puzzles many: why don’t state capitals match up with the largest cities in their states? The short answer is that historical, political, and geographic reasons combined lead to most state capitals being smaller cities—not the bustling metropolitan hubs we tend to associate with states. Let’s take a closer look through a historical and practical lens to understand this curious phenomenon.

Imagine going back to the early 1800s when many states were freshly established. Back then, the cities chosen as capitals were often the largest or most strategically placed settlements. Albany, New York is a great example. In 1810, Albany was actually the 10th largest city in the entire U.S.—quite a player on the national stage. So initially, the capitals made sense as populous, central places primed for governance.

But after founding, things changed rapidly. Enter the Industrial Revolution. This era ignited fast-paced growth in other cities, often in areas rich in resources or industry. Pittsburgh, for instance, exploded into a steel powerhouse, far outgrowing Pennsylvania’s capital, Harrisburg. Similarly, Las Vegas boomed after Nevada’s founding, and Chicago also outstripped Springfield, Illinois, in size and influence.

So what happens when a city grows huge after the capital is fixed? The capital doesn’t just up and move, does it? Well, sometimes it does. Illinois is a case in point. The state shifted its capital from Kaskaskia to Vandalia, and then to Springfield, trying to find the right political and geographic fit. This isn’t just a random shuffle; it often reflects efforts to dodge corruption and to pick spots more central for the state’s population.

Why dodge commerce? Because big commercial centers carry baggage—powerful business interests can entangle government in potentially corrupt alliances. Moving a capital away from economic hotspots helps keep government operations a bit more impartial and insulated from those forces.

Another key factor is geography. In the 19th century, many states wanted governments located near their population centers, or at least centrally to all citizens. Look at Sacramento, California. Sacramento sits nicely between the gold fields and San Francisco. While San Francisco was bigger and more commercially important, Sacramento’s central location made it more accessible for the average citizen. Likewise, Jackson, Mississippi, was chosen for being centrally located, even though it sat in a largely underpopulated part of the state back then. Oklahoma City follows the same reasoning.

There’s also the issue of port cities. Many largest cities in states are coastal or major ports—think Miami in Florida or Seattle in Washington. Such cities, despite their size, are often on the edges of the state, making them impractical as state capitals. It’s tough to govern a large, sprawling state from a spot that favors one region over others.

Capitals often serve as transportation hubs, too, situated where travel and communication with the rest of the state is easier. This strengthens their role as political and administrative centers. Sacramento again fits the bill—accessible via navigable waterways and railroads, it was a natural hub compared to Monterey, the previous California capital.

In short, the reason most U.S. state capitals aren’t the biggest cities boils down to a mix of history, politics, and geography:

- Many capitals started as largest cities, but boomtowns grew on industrial or commercial strength afterward.

- Some capitals were relocated to reduce corrupt influence from booming commercial hubs.

- Central location was prioritized for democratic representation and access.

- Port cities, often the largest, are on edges and less practical as statewide centers.

- Capitals often doubled as transportation and communication hubs.

The next time someone asks “Why isn’t the capital the biggest city?” you can confidently say it’s a story of careful balance. Lawmakers aimed to keep governance fair, accessible, and geographically sensible—not just put the capital where the skyscrapers stack highest. Sometimes, that means power shifts away from the city lights to a quieter political heart of the state.

“Location, location, and a bit of political caution” sums it up pretty well.

If you’re curious, try comparing your own state. Is the capital a quiet historic town or a booming urban center? Did it move at some point? Those stories often reveal fascinating slices of American history and governance—and maybe a lesson on the limits of mere size when politics is involved.