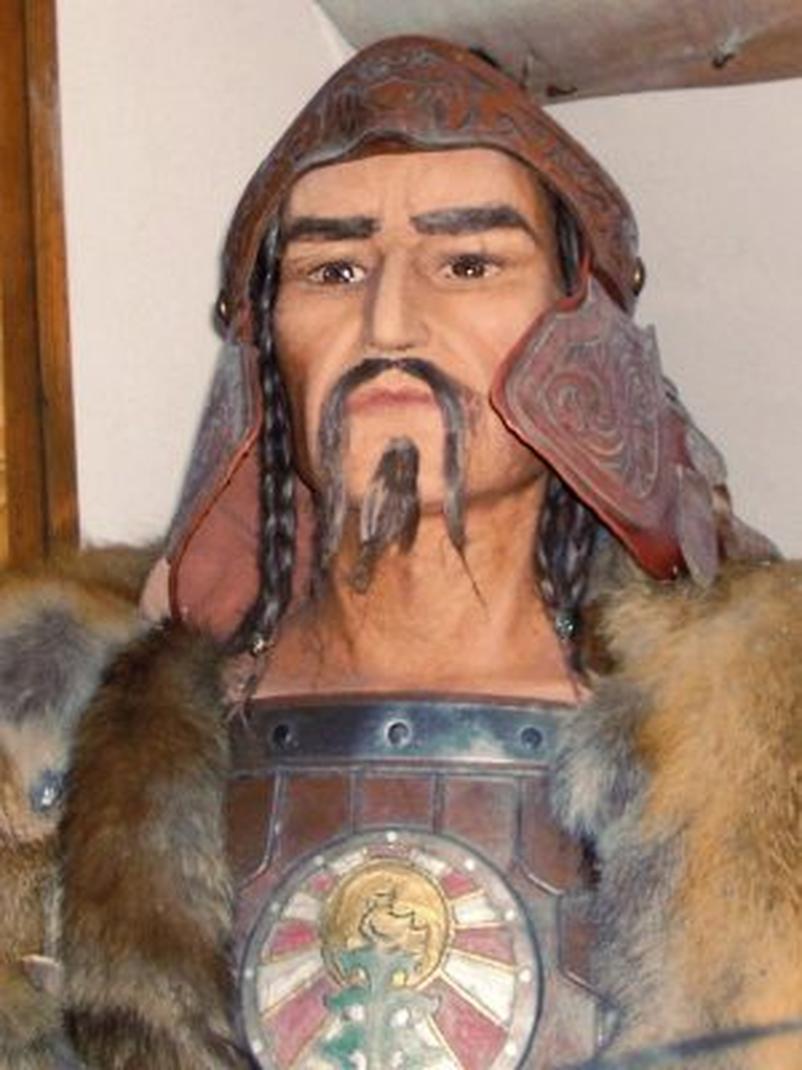

Figures like Genghis Khan and Attila, despite their massive genocides, are often revered and described as “conquerors” due to a complex mix of historical revisionism, cultural bias, political factors, and evolving perspectives on their rule beyond just violence and conquest.

Historically, narratives painted these figures as ruthless villains, emphasizing conquest and massacre. Modern historians have shifted focus towards their multifaceted roles. For instance, Jack Weatherford’s popular 2004 book, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, highlights the unification of Eurasia, peace, and trade revived under the Mongol Empire. His work helped reshape Mongol history by pointing out positive traits, such as religious tolerance, promotion of trade through the Silk Road, and surprisingly progressive governance relative to their times.

The Mongol Empire’s control brought stability over vast areas, reducing local conflicts and enabling commerce. Stories circulated that under Mongol rule, travelers could cross Asia safely with valuables, a testament to order and protection of property. They tolerated various religions and implemented laws outlawing common social evils like slavery and kidnapping. Genghis Khan’s upbringing as an underdog who united tribes resonates with many as a story of social reform and national consolidation.

Much of the atrocity data also suffers from exaggeration. Medieval chroniclers, often enemies or victims of Mongol expansions—such as Chinese, Persian, or European sources—had incentives to demonize them. These accounts sometimes inflate death tolls and focus on gruesome anecdotes not always supported by corroborative evidence. For example, claims linking the Mongols to massive massacres sometimes conflate events over time or attribute deaths to causes such as the Black Plague, which spread later and unrelated to direct Mongol violence.

Revisionism also arose as scholars questioned why Western imperial conquerors like Alexander the Great or European crusaders were often romanticized while Asian conquerors faced relentless vilification. This imbalance links to a Eurocentric bias in historical writings, where Western historians accorded classical conquerors heroic status but portrayed non-Western leaders as barbaric. The portrayal of Mongols as bloodthirsty villains became ingrained during the European Enlightenment, with figures like Montesquieu and Voltaire reinforcing stereotypes of “Oriental despotism” and cruelty.

Such biases stem from deep-rooted cultural and political rivalries. Sedentary empires that suffered under Mongol incursions, including the Roman, Chinese, Persian, and Byzantine states, propagated negative images to justify their resistance. Meanwhile, Mongols killed mainly aristocrats and ruling classes, sparing common people to simplify governance. Genghis Khan’s distrust of elites reflects his personal background in tribal conflicts. Post-conquest periods showed less indiscriminate violence than often assumed.

Historical documentation is challenging. Steppe nomads like the Huns and Mongols relied on oral traditions rather than written records, causing modern historians to depend mainly on second-hand hostile sources. The Secret History of the Mongols, a rare native epic, blends heroic narrative with facts, complicating efforts to segregate myth from history.

In addition, political developments influence historical rehabilitation. Modern Mongolia’s revival after communist rule spurred national pride. Genghis Khan became a symbol of identity and strength, not just conquest. Elsewhere in Central Asia, descent from Genghis remains a status marker. Contemporary Western interest in balanced global history encourages revisiting these complex figures, recognizing their role in shaping Eurasian civilization, culture, and trade networks.

In summary, Genghis Khan and Attila are revered as conquerors rather than universally repudiated for their atrocities because:

- Historical narratives have shifted from purely villainous portrayals to nuanced views highlighting governance, trade, and law.

- Bias in medieval and early modern sources exaggerated their brutality while glorifying Western conquerors.

- The Mongol Empire brought relative peace, prosperity, religious tolerance, and unification to large regions.

- Selective violence mostly targeted elites, facilitating easier rule over conquered peoples.

- Modern political and cultural factors, especially Mongolian nationalism, support rehabilitation and pride in their legacies.

- Source scarcity and intertwining of myth and fact complicate straightforward condemnation.

This combination of historiographical revision, cultural context, and political symbolism explains why such figures often appear as “conquerors” rather than mere perpetrators of atrocities.

Why Are Genghis Khan and Attila Revered as “Conquerors” Despite Their Atrocities?

Simply put: They are called conquerors instead of being repudiated for atrocities because history is messy, biased, and often written by the victors—or, intriguingly, by the vanquished themselves, who needed convenient villains. This mix of factors involving revisionist histories, cultural perspectives, propaganda, and political needs colors the way these figures are portrayed even today.

Let’s unravel this tangled yarn ball with some context, stories, and a pinch of humor to keep things spicy.

The Earlier View: Villains Straight Out of a Medieval Horror Flick

For centuries, figures like Genghis Khan and Attila were painted as monstrous brutes—basically the original bad guys. Medieval chroniclers from the empires the Mongols and Huns ravaged weren’t exactly subtle with their narrative tones. Their histories broadcast unmatched massacre accounts and terrifying tales that still echo in popular consciousness.

But, here’s the kicker: much of this “evidence” turned out to be propaganda crafted by those terrified sedentary empires—Rome, Byzantium, Persia, China—desperate to justify their own failures and losses. If you were on the sidelines wiping sweat from your brow because these nomads were swarming your lands, you’d also probably exaggerate just a bit, right?

Historical Revisionism: When Historians Grab the Mic

Fast forward to the early 2000s—Jack Weatherford’s Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World shook up the traditional narrative. Suddenly, instead of just a bloodthirsty savage, we’re seeing Genghis as a unifier, a lawgiver, and an innovator whose empire reconnected trade across Eurasia with the Silk Road. People were like, “Hold up, that guy who crushed cities also made it safe to carry a pot of gold from China to Europe?” Yep.

Weatherford and others began stressing the Mongolia empire’s positive impacts: religious tolerance (a big deal for the era), promotion of trade networks, and relative gender progressiveness for the time. It’s almost like Genghis had this progressive streak amid the carnage.

Also, the question arises: Were the medieval atrocity numbers accurate? Probably not entirely. Medieval historians are to accuracy what a tabloid magazine is to investigative journalism. Their accounts need skeptical reading.

Why the Selective Memory? Eurocentrism and Orientalism Have a Lot to Do With It

Let’s get real: the glorification of conquerors like Alexander the Great or Roman emperors and the demonization of Asian figures like Genghis Khan is steeped in Eurocentric biases. Western classical tradition favored Greek and Roman narratives and, for centuries, dismissed or demonized Eastern empires as mere “barbarians.”

This skew in the historical lens meant the often bloody exploits of Western conquerors could be romanticized as bold and civilizationally progressive while Asian and steppe leaders were cast as ruthless monsters. It’s like giving one kid a gold star for making a mess and scolding the other for drawing outside the lines—historical bias, anyone?

Plus, the “Secret History of the Mongols,” their own epic narrative, has been largely sidelined or taken as mythology, giving the rest of the world an incomplete picture.

Stability, Trade, and Religious Tolerance: The Odd Self-Contradiction of the Mongols

Despite their fearsome reputation, the Mongols under Genghis Khan actually created an unprecedented order:

- Unification of most of Eurasia: The most expansive land empire in history brought peace between previously warring factions during its rule.

- Trade facilitation: Restarting and securing the Silk Road boosted commerce unparalleled in scale.

- Religious tolerance: The Mongols allowed faiths to flourish rather than impose one creed.

- Relative progress: Compared to contemporaries, they had less gender oppression and outlawed slavery and kidnappings.

Imagine being able to travel thousands of miles carrying gold without fear—sounds like a modern bank vault, but in medieval times, that was revolutionary.

Genghis Khan’s Personal Story: More Complex Than Just Massacres

Genghis Khan wasn’t born with a silver spoon. Historians note his upbringing was harsh and filled with betrayal. This background explains why he mistrusted aristocrats hugely and why he often executed only nobles after conquest, replacing them with loyal generals. There’s a psychological layer to his selective violence that’s worth noting.

His outlawing of feuds, slavery, and kidnapping shows a leader looking to stabilize and unify, rather than simply destroy. While his campaigns were brutal, some of the violence targeted only those who held power, enabling the Mongols to govern newly acquired lands more smoothly.

Did the Mongols Really Murder Millions? The Plague’s Grim Role

Many attribute the massive death tolls linked with the Mongol expansions directly to their brutality. However, historians point out that the Black Death, arriving decades after Genghis Khan died, was responsible for vast deaths initially pinned on him and his armies.

Those gruesome tales, like the Mongols catapulting plague-infected bodies over city walls, are more legend than fact. Interestingly, Mongols respected their dead and reportedly punished anyone who disrespected corpses. So, not exactly the plague-spreading maniacs history sometimes makes them out to be.

Who Loved the Mongols? Not Everyone Hated Them

Culturally, the Mongols had admirers too. Medieval and early Renaissance people across some regions saw them in a positive light. For example, many Central Asian elites traced their lineage to Genghis Khan with pride. Mongolia today celebrates him as a founding national hero.

Meanwhile, China’s Ming dynasty despised the Mongols—hardly surprising given the bitter history. But this variation reminds us that historical reputations depend heavily on perspective.

Political and Cultural Factors that Shape Modern Views

The image of Genghis Khan and similar figures didn’t become twisted into “bloodthirsty barbarians” until the Enlightenment period in Europe. Thinkers like Montesquieu and Voltaire used these conquerors symbolically to criticize what they called “Oriental despotism,” bolstering an idea of Western superiority.

Adding fuel, 19th-century scientific racism dehumanized Mongols further. The infamous misnaming of Down Syndrome as “Mongoloid” is a chilling example of this prejudice. This constructed “otherness” kept Mongols symbolically locked in a cage of barbarism in Western imaginations.

At the same time, modern Mongolian nationalism has revived and celebrated Genghis Khan’s legacy after decades of communist repression. It is a rare, powerful example of history being reclaimed to foster identity and pride.

Sources Are Messy: How Reliable Are Our Tales of Conquest?

Most accounts of the Mongols come from their enemies’ pen—hardly an unbiased view. Native steppe writings are sparse or were ignored for centuries, leaving gaps filled with myths or propaganda.

Moreover, historical narratives from over two centuries of Mongol rule often blur events from distinct times, causing further confusion. Blaming Genghis Khan for the entire empire’s actions over 150 years isn’t fair or accurate.

Even the celebrated Secret History of the Mongols reads more like a heroic epic than a strict historical document. It’s storytelling, not journalism.

So, What Can Readers Take Away?

History is not black-and-white. Genghis Khan and Attila were brutal conquerors but also complex leaders who shaped civilizations and histories in huge ways.

The reverence and labeling as “conquerors” reflect:

- Changing historical interpretations that look beyond atrocities.

- Biases in Western and non-Western historiography.

- Political and cultural motivations both in the past and today.

- The necessity to consider multiple perspectives, including those once suppressed.

- The realities that large-scale violence in ancient times was often normalized and comparatively selective.

Next time someone pops the phrase “mass murdering barbarian” about Genghis Khan, try flipping the historical coin. What about his laws against kidnapping? His tolerance of religions? His caution in overthrowing aristocrats rather than everyone? Did you know he may have been one of the first to allow free religious practice across a vast empire?

Understanding these nuances helps us give credit to the full story—not just the gory headlines. Was Genghis Khan a conqueror? Absolutely. Was he a genocidal monster? He was brutal, no question. But history isn’t a courtroom for absolutes, it’s a lens for complex human stories.

So, can we celebrate and repudiate at the same time? Maybe so. History’s messy—and that’s why it’s so fascinating.