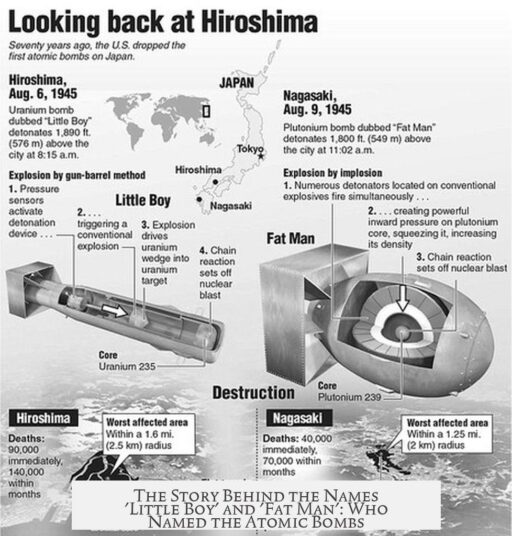

The names “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” for the atomic bombs originated during the Manhattan Project as informal code names, primarily serving as simple mnemonic devices rather than carrying deep symbolic meaning. These names helped differentiate bomb designs without disclosing sensitive material. Their exact origin is disputed among project members, leaving some ambiguity.

Robert Serber, a physicist involved in the project, claimed decades later that he coined the names. Initially, the uranium gun-type bomb was called the “Thin Man,” named after a detective character from the 1930s–40s Nick and Nora films. When the design was scaled down, it became the “Little Boy.” Serber also claimed he originated “Fat Man” for the larger plutonium bomb, inspired by the character Sydney Greenstreet in the film The Maltese Falcon. These nicknames reflected the bomb shapes—thin and elongated versus round and bulky.

Alternatively, Norman Ramsey, another physicist working closely with ballistics, provided a contemporaneous explanation from 1945. He indicated the “Thin Man” and “Fat Man” names were used during full-scale testing exposure, with “Fat Man” describing the wider plutonium bomb casing. Ramsey attributed the names partly to Air Force officers who aimed to mask modifications made to their B-29 aircraft for carrying the bombs, making the names internal code words. He noted “Little Boy” emerged later for the modified uranium gun design. However, Ramsey does not claim personal authorship of the names.

Both accounts acknowledge the nicknames’ function as code terms avoiding technical or sensitive words like “uranium” or “plutonium.” The names were intended to disguise the actual nature of the bombs in communications. Using humanized or cinematic references helped personnel remember and discuss the devices without raising suspicion.

| Name | Meaning | Origin Claim |

|---|---|---|

| Thin Man | Early uranium gun-type design, slender shape | Named by Serber, referencing Nick and Nora films |

| Little Boy | Downscaled uranium bomb design | Evolved from “Thin Man” per Serber and Ramsey, mnemonic |

| Fat Man | Plutonium implosion bomb, wide shape | Named by Serber (film character) or Air Force officers (Ballistics context) |

- Both names centered on physical shape to distinguish designs.

- Code-words avoided using technical terms minimizing leaks.

- Authenticity of who exactly named them remains inconclusive.

In short, these names came from informal project culture, with some basis in contemporary film characters and descriptive shapes. Their main purpose was practical, aiding communication while preserving secrecy during wartime.

- “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” were mnemonics and code names for bomb designs.

- Robert Serber claims to have named both, inspired by film characters and design shape.

- Norman Ramsey suggests names originated from Air Force efforts to mask aircraft modifications.

- The names avoided using technical terms for secrecy.

- Precise attribution is uncertain due to conflicting memories and accounts.

Who Exactly Decided to Name the Atomic Bombs ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’? Unveiling the Mystery and Meaning Behind These Names

The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki carry names that sound strangely innocent. Who exactly chose to call them Little Boy and Fat Man? And was there any deep meaning behind these labels? Let’s peel back the layers of history and hear from those who were there.

First off, the story isn’t wrapped up in neat little bows. It comes with conflicting accounts, kindly reminding us that human memory isn’t always perfect, especially about events this momentous. So buckle up as we dive into the tale!

The Origin of the Nicknames: A Tale of Two Physicists

The first claim comes from Robert Serber, a physicist on the Manhattan Project. Decades after the war, Serber said he named the two bombs. He says “Little Boy” evolved from an earlier design called “Thin Man.” This original design got its name from Nick and Nora Charles, a detective duo popular in movies from the late 1930s and early 1940s. The “Thin Man” bomb was longer, so the nickname fit well.

As the design changed and became shorter, it lost its slender silhouette, hence the transition to “Little Boy.” What about “Fat Man?” Well, Serber credits the name as his idea too, inspired by the portly villain played by Sydney Greenstreet in the classic film noir The Maltese Falcon. It’s kind of like naming your bombs after classic Hollywood characters— a bit quirky for such serious devices, right?

In contrast, Norman Ramsey, another physicist who worked closely on the project’s ballistics, recorded his version sooner—in September 1945, closer to the events themselves. Ramsey’s account carries some weight because of his intimate involvement with ballistic testing at Project Alberta.

He notes that the early gun-type plutonium design was mockingly called the “Sewer Pipe Gun” during tests at the Dahlgren range. When full-scale tests kicked off in 1943, the design nicknames “Thin Man” and “Fat Man” emerged, but he insists these came from Air Force officers. Apparently, they wanted innocuous-sounding code names to disguise modifications made to B-29 bombers for Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt.

Ramsey explains that “Little Boy” was a later name relating to the shift toward a uranium gun design, presumably smaller or more compact. However, he doesn’t claim to have coined the names himself, suggesting they originated for practical cover-up reasons rather than personal whimsy.

So whose story holds up? The historian’s perspective leans toward Serber’s narrative but acknowledges how stories get tangled. Memory slips, informal jokes, classified secrecy, and cross-talk all help create these overlapping accounts. Maybe both versions have a kernel of truth; or maybe war-time secrecy and lack of documentation leave us with a puzzle.

What’s in a Name: Practical Mnemonics or Secret Codes?

Beyond individual inventiveness, the choice of these names came down to operational secrecy and clarity. The project needed simple, memorable code names—code words that wouldn’t give away sensitive information if overheard or intercepted.

The words “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” helped distinguish different bomb designs without revealing their nature. The terms purposely avoided triggering curiosity or alarmers that terms like “uranium gun” or “plutonium bomb” might raise. Imagine the confusion if someone stumbled on “Fat Man” without context, thinking it was a nickname for a general or a railway engine, rather than a weapon of mass destruction.

This practice of using harmless-sounding nicknames fits into wartime intelligence strategies: make your true intentions opaque while keeping teams on the same page. It’s like whispering a secret with a smile, assuming no one at the party gets it.

Interestingly, this naming approach contrasts with the names of many military projects, often filled with grandiose labels or brutally practical code names. In this case, there’s a mild humor, a nod to popular culture, and an emphasis on covert simplicity.

Why Does It Matter? The Legacy of These Names

Why care about who named these bombs or what their names meant? Because these names humanize a chapter of history marked by horror and heroism. They remind us that even in the darkest times, people turned to humor and culture to ease tension.

Knowing the origin stories also highlights the fascinating interplay between scientific innovation, military secrecy, and popular culture. The names reflect how those involved tried to keep a handle on an overwhelming project, mixing practicality and creativity to get the job done.

Moreover, understanding the naming clarifies how different teams within the Manhattan Project saw the bombs. For some, the names were straightforward mnemonics. For others, perhaps, a coded nod to the bombers or an inside joke referencing detective films and gangsters.

This blend of seriousness and whimsy makes history feel less like a dusty textbook and more like a conversation with people navigating something extraordinary.

Lessons and Takeaways

- The naming of the “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” was not a grand design but a practical approach to code-naming complex weapons discreetly.

- Robert Serber likely originated the nicknames, inspired by popular films, but memories and stories vary.

- Norman Ramsey provides a more bureaucratic perspective, suggesting the Air Force influenced the names for secrecy and operational security.

- The names served as mnemonic devices and secret codes, avoiding outright references to nuclear materials or bombs, crucial for hiding intent from prying eyes.

- The story reflects how culture, secrecy, and practicality combined even in the most critical historic moments.

So next time you hear “Little Boy” or “Fat Man,” you’ll know these names weren’t chosen lightly. They carried layers of meaning — some playful, some strategic — and helped the people behind history’s deadliest weapons keep their secret safe.

What do you think? Would you have come up with a more creative name? Or maybe “Fat Man” and “Little Boy” nailed that mix of subtlety and whimsy?