There were slaves in Europe, but not in the same way or scale as in the United States. European slavery was largely limited to prisoners of war, criminals, and debtors forced into unpaid labor. In contrast, American slavery was a widespread, race-based system built around plantation economies reliant on African slave labor. European slavery faded earlier, replaced by serfdom, while American slavery persisted until the 19th century and ended under different economic and moral pressures.

Slavery in Europe and America developed under very different circumstances. In America, European colonizers needed a large, cheap, and reliable labor force to exploit newly acquired land. Early efforts using indigenous peoples and indentured servants failed due to high death rates and temporary commitments. This created a demand for a more permanent labor force. The Atlantic slave trade fulfilled this need by supplying millions of Africans, who endured brutal conditions on plantations growing cash crops like cotton and tobacco.

Europe faced no such economic imperative. Its agriculture was less labor-intensive, based mainly on locally available peasants and serfs. Large-scale plantations did not exist because growing crops like wheat and tending cattle did not justify the high cost of purchasing slaves. Instead, European slavery was more fragmented and limited. Prisoners taken in tribal warfare, criminals, and debtors were forced to work without pay but not on the same scale or under similar conditions as in the Americas.

European slaves were not typically of African origin. Except for small numbers brought to southern ports in Spain and Portugal, African slaves were rare in Europe due to an existing and extensive labor source: peasants and serfs. The Catholic Church also strongly influenced European slavery by banning the enslavement of Christians early in the medieval period. This religious prohibition shaped labor systems toward serfdom rather than chattel slavery.

Serfdom was the dominant labor system in Europe from roughly the 9th century, replacing earlier forms of slavery. Serfs were legally bound to the land they cultivated and could not leave without permission but were not owned outright as slaves. This system persisted in parts of Europe into the 19th and even early 20th centuries, notably in Russia. Its development corresponded with the collapse of Roman authority and the lack of large centralized states that had historically supported slave-owning classes.

The legal situation also differed markedly. A landmark British court case in 1772, known as the Somersett Case, ruled that slaves were freed upon arrival in Britain, effectively ending chattel slavery there. This discouraged aristocrats from bringing slaves into Britain, as enslaved persons became free by virtue of British law. While some wealthy families kept slaves as status symbols inside Britain, such instances were rare and mostly limited to domestic service.

Slavery in colonial America ended primarily due to economic and moral forces. Britain abolished the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1807, reducing the supply of enslaved Africans. The independence of Spanish American colonies and the rise of industrialization shifted labor systems toward wage labor. Moral opposition to slavery gained momentum, leading to abolition in European colonies and the United States post-Civil War. Brazil was the last to abolish slavery in the Americas during the late 19th century.

European colonial powers later managed African labor differently, ostensibly abolishing slavery but often enforcing labor conditions akin to it. Colonial companies paid workers extremely low wages under harsh conditions, and some regions practiced indirect rule that perpetuated forms of servitude or bondage resembling slavery. The notorious Congo Free State exemplified extreme exploitation until reforms were forced in the early 20th century. Independence movements between the 1950s and 1970s finally dismantled many such exploitative systems on the continent.

Religion played a significant role in shaping slavery’s trajectory in Europe and the Americas. Christianity forbade enslaving fellow Christians, which shifted European labor systems away from chattel slavery. In contrast, during American colonization, theological justifications held that indigenous peoples were to be converted rather than enslaved, whereas Africans who “refused” Christianity could be legally enslaved, creating a religiously framed racial hierarchy that did not exist in Europe.

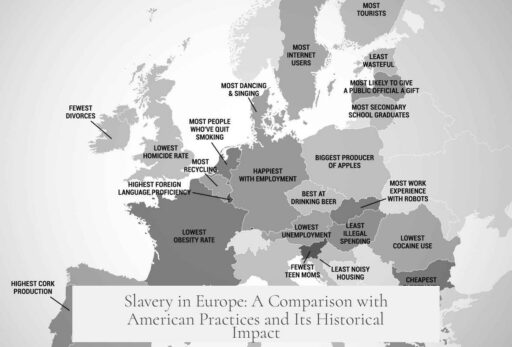

| Aspect | Europe | America (US/Colonies) |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Small-scale, limited mostly to prisoners, criminals, debtors | Large-scale, plantation-based labor on cash crops |

| Labor system | Serfdom largely replaced slavery by 9th century | Race-based chattel slavery persisted until 19th century |

| Origin of slaves | Mostly local prisoners, minimal African slaves | Majority African slaves imported via trans-Atlantic trade |

| Legal/moral context | Christianity banned enslaving Christians early on; Somersett Case ended slavery legally in Britain | Slavery abolished after economic changes, wars, and moral opposition |

In summary:

- Europe had slavery but it was limited, mostly non-racial, and replaced by serfdom.

- American slavery was large-scale, racialized, and linked to plantation economics.

- Legal and religious frameworks in Europe restricted slavery among Christians early on.

- Slavery ended in Europe earlier due to political collapse and economic shifts.

- In America, it ended due to abolitionist movements, war, and industrialization.

- Africans were rarely enslaved in Europe itself, mostly in America.

- European colonialism later imposed harsh labor systems in Africa resembling slavery.

Where There Slaves in Europe the Same Way as in the US? What Happened With Them?

Short answer? No, slavery in Europe was not the same as in the US, and their fates diverged dramatically. That’s the headline takeaway, but a peek under the hood reveals a fascinating story of economics, warfare, religion, and society—often surprising and complex.

Let’s unpack this topic carefully. Did Europe have “slaves” like in the Americas? How did these systems work? Why did slavery vanish differently on either side of the Atlantic? And what became of those enslaved or unfree workers?

1. Slavery’s Different Beginnings: Europe vs. America

The roots of slavery in Europe and America spring from very different soils. Europeans colonized the Americas with a hunger for wealth. Sweet, cash-hungry crops like sugar, tobacco, and cotton needed brutally intensive labor. Removing the indigenous population’s initial labor source was tragic and swift—diseases and overwork were deadly foes.

Indentured servants from Europe filled labor gaps temporarily but weren’t reliable. Enter African slaves: cheaper, permanent, and—through horrific means—more controllable. In the 17th century, European traders dove into Africa to buy slaves in huge numbers. This system was racially coded and designed explicitly for economic exploitation.

Europe, meanwhile, rolled a very different dice. There was no sudden gold rush of plantations needing endless cheap workers. Their economies mostly relied on peasants, serfs, and small-scale farming—not massive cash crops like the Americas. Slaves existed but as a smaller component, derived mostly from prisoners of war, criminals, or debtors forced to labor without pay.

In classical Europe—Greece, Rome—slavery was extensive but tied to specific land-owning elites, not broad commercial ventures. Mines, domestic help, even entertainment roles were filled by slaves, but no massive plantation complexes demanded slave armies.

2. What Happened to European Slavery?

Why did Europe’s slavery fade out while American slavery entrenched and expanded? Let’s break down the factors.

After Rome’s fall, Europe fractured. Large state systems that supported slavery collapsed. New economic systems—like serfdom—emerged. Serfs were peasants tied to the land, not slaves in the classic chattel sense. They owed service to lords but were not owned outright. This subtle distinction mattered law-wise and socially.

The Catholic Church also played a role, forbidding the enslavement of Christians, pushing European labor systems away from racial or permanent slavery. A slave could theoretically win freedom on conversion or arrival in Christian lands. The famous 1772 Somersett Case in Britain confirmed this, ruling slaves freed upon setting foot there.

So, slavery in Europe transformed, diminished, and often blurred into serfdom or other unfree labor forms—not the massive, race-based plantation slavery of the Americas.

3. Slavery’s American Picture

Across the ocean, slavery was a beast of different character. Economy, demographics, legal precedents, and racism fused into a system where millions of African slaves labored on plantations. Harsh and brutal, it boosted profits for European colonizers and later American planters.

Africans were forcibly uprooted and shipped in horrific conditions, unlike Europe, where Africans were rarely brought in bulk. Plantation death rates were notoriously high but compensated by continuous importation—until Britain banned the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1807.

Economic and moral shifts eventually brought slavery to a close. The British, industrialized and committed to free trade, no longer needed slaves. Independence movements, moral opposition, and industrial labor systems weakened slavery’s grip. The US Civil War finally ended it domestically, while Brazil took until the late 19th century under imperial influence.

4. How Did Race Factor Into These Systems?

In Europe, enslaved people were mostly locals—prisoners captured in war, criminals, or debtors. Race was largely irrelevant to enslavement. The population was relatively homogenous, and Christian doctrine prevented enslaving fellow Christians.

In America, racial identity became an unfortunate cornerstone. Africans, considered non-Christian “others,” were enslaved in massive numbers. This laid foundations for systemic racism and social hierarchies that echoed well into modern times.

5. What About African Slavery Under Colonial Rule?

After abolishing slavery in their empires, European powers colonized Africa. They did not reinstate classic slavery. Instead, exploitative systems—poorly paid, often forced labor—mimicked slavery under different names.

- Companies paid wages so low workers were trapped economically.

- Indirect rule maintained some pre-colonial servitude or slavery-like systems.

- The horrific Congo Free State used forced labor outright, but international pressure forced reform.

Fortunately, independence movements in mid-20th century Africa ended these exploitative practices, although labor abuses persist in various shapes today.

6. Why No Mass African Slavery in Europe?

Europe had ample local labor alternatives. Peasants and serfs fulfilled most economic needs. Importing African slaves en masse didn’t make economic sense for local agricultural systems producing non-cash crops like wheat or cattle.

Moreover, the Church banned enslaving Christians. If Africans converted, or if Africans were treated as “Christian brothers,” it complicated justifying slavery legally and morally.

Meanwhile, the Somersett Case (1772) ensured any slave brought to Britain was automatically free, removing incentives for European slave owners to bring slaves home.

7. Overview: The Divergent Trajectories of Slavery

| Feature | Europe | Americas |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Smaller, localized, tied to war prisoners and debtors | Massive, plantation-based, race-driven |

| Economics | Low labor intensity, serfdom replaced slavery | High labor intensity, cash crops, sustained slave importation |

| Race Factor | Minimal, non-racial | Racially based system targeting Africans |

| Religion | Christianity forbade Christian enslavement | Initially justified enslavement of non-Christians |

| End of System | Disappeared after fall of Rome, replaced serfdom | Ended through abolition movements, wars, economic shifts |

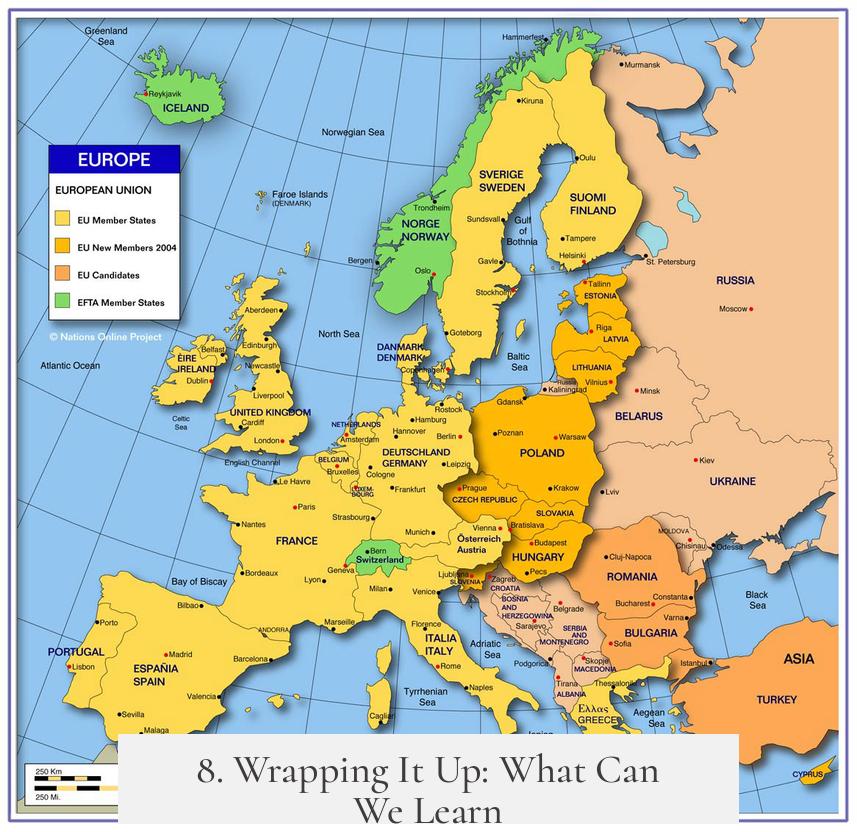

8. Wrapping It Up: What Can We Learn?

The question of “Were there slaves in Europe as in the US?” is a gateway to understanding how economics, geography, religion, and law shape human rights. Europe’s slavery was mostly a local phenomenon revolving around war captives and debt. The form of forced labor migrated into serfdom, with church influence and changing political landscapes ending classic slavery.

In contrast, the Americas represent a system where slavery was industrialized and racialized, becoming a legacy with deep societal scars.

So, next time you hear about slavery, remember it didn’t wear the same face everywhere. Sometimes, context writes history with vastly different scripts.

Curious to dig deeper?

Consider exploring the Somersett Case or the transformation from Roman slavery to medieval serfdom. Also, the aftermath of abolition in Africa raises important lessons on labor rights and exploitation.

Why do some forms of exploitation linger longer than others? What forces allow societies to build systems of dignity and justice? That’s a conversation worth having.

Were there slaves in Europe like in the US colonies?

Europe had slavery but not like in the US. Slavery in Europe grew mainly from prisoners of war, criminals, and debtors. It was smaller in scale and mostly for domestic work or mines, not plantation labor.

Why didn’t Europe develop large-scale plantation slavery like America?

Europe had many farmers and less need for intensive slave labor. Its economy lacked cash crops like cotton or tobacco that required vast labor forces. Peasants and serfs provided much of the needed workforce.

What ended slavery in Europe compared to America?

In Europe, large states fell and serfdom replaced slavery. The Church banned enslaving Christians early on, and laws like the Somersett Case freed slaves in Britain. In America, abolition was driven by industrialization and moral opposition.

Were African slaves brought to Europe in large numbers?

Generally no. Africa’s slaves were rarely brought to Europe except small numbers in Spain and Portugal. Europe had enough local labor in peasants and serfs, so a large African slave population was unnecessary.

How did religion affect slavery in Europe?

Christianity forbade enslaving fellow Christians. This shifted Europe toward serfdom instead of chattel slavery. In the Americas, Africans were enslaved because they were seen as non-Christians resisting conversion.