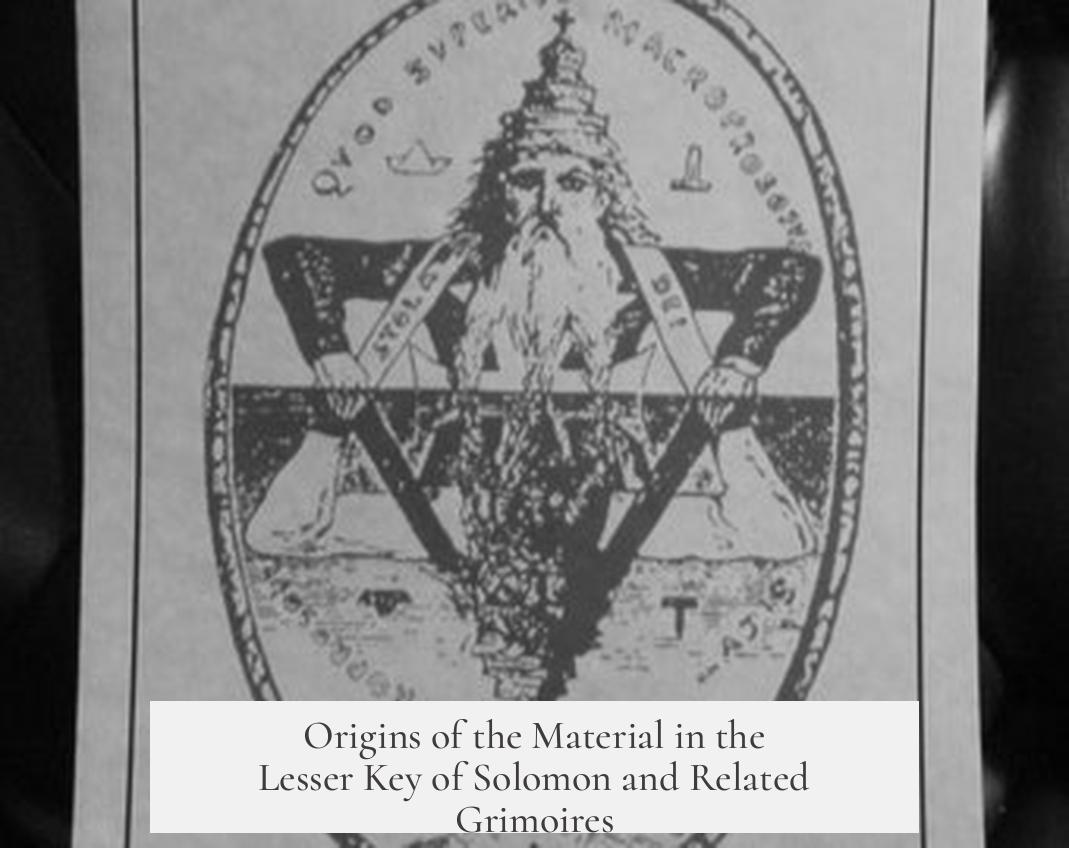

The material in the Lesser Key of Solomon and similar grimoires originates from a complex mix of sources, including borrowed names from earlier traditions, corrupted or transformed names from various languages, apocryphal religious texts, and creative inventions by magicians and scribes. These texts are products of evolving religious, linguistic, and magical traditions spanning centuries.

The names of spirits and demons found in these grimoires often trace back to older mythologies, religious beliefs, and folkloric entities. Some names are directly borrowed from existing traditions. For example, faeries appear in some magical books, like The Book of Oberon: A Sourcebook of Elizabethan Magic, showing an overlap between fairy lore and demonology in grimoires.

Many spirit names underwent significant changes over time. Manuscripts were copied by hand, often translated and transliterated from languages such as Hebrew, Greek, or Egyptian into Latin, English, or other European tongues. This process introduced mistakes and spelling variations. These corruptions sometimes made original names difficult to recognize.

| Example | Original Source | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Balam | Biblical magician Balaam / Semitic term Baal | The name Balam in the Lesser Key of Solomon might derive from Balaam, a biblical figure. The term Baal means “lord” and was applied to deities later demonized. It also connects to the Hebrew “ba’al shem” meaning “Lord of the Names,” referring to magicians who used secret divine names. |

The relatively few proper names of demons and angels in canonical religious texts contrasts with later apocryphal literature, particularly from the second century BCE onward. Texts such as extra-canonical apocalyptic writings provide many individual names of spirits, both good and evil. For instance, angels like Gabriel and Michael appear in the Book of Daniel, but many others are only found in apocryphal sources, reflecting an increasing personalization of spiritual beings.

These apocryphal texts help explain the origin of many occult names used in grimoires. They offer more detailed information about spirits and sometimes provide attributes or powers. Some of the “barbarous names” employed in rituals are not simply fabricated nonsense but derive from these mysterious and lesser-known traditions outside official religious canons.

Yet not all names in grimoires come from older sources. Some were invented, either by the original compilers or by later occultists. Magicians throughout history have created new words to fit their purposes. A famous modern example is Aleister Crowley’s alteration of “Abracadabra” to “Abrahadabra.” Similarly, H.P. Lovecraft devised names like Cthulhu and Nyarlathotep for his fiction, which were later incorporated into occult practices by figures such as Kenneth Grant.

This pattern demonstrates the ongoing evolution and creation of magical language. It is reasonable to believe similar inventions took place in earlier eras. Many original authorial attributions are lost to time, obscuring the origins of some names we encounter today.

The motivations for writing grimoires are varied and often unclear. Some were produced out of genuine religious devotion, possibly inspired by visions, dreams, or received revelations. Others sought to organize, categorize, and systemize existing magical practices and lore, similar to scholarly compilations like the 19th-century Dictionnaire Infernal. Many grimoires defy simple explanation regarding their origin or intent.

Language plays a critical role in the transmission and transformation of magical names. Misunderstandings and reinterpretations of Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and other languages resulted in new magical words. For example, some Italian grimoires include English phrases that were misunderstood or adapted as mystical words. As research expands, fewer names are considered purely invented, since many can be linked to linguistic or cultural sources, although some independent creations remain.

- Grimoires combine older mythologies, apocryphal religious texts, and local folklore with magic practices.

- Many demon and spirit names in the Lesser Key of Solomon evolved from mistranslations and corruptions of Hebrew, Greek, or Semitic terms.

- Apocryphal and extra-biblical literature introduced many named spirits absent from canonical religious texts.

- Authors and magicians periodically invented new names for esoteric and ritual purposes across history.

- Understanding grimoires requires examining religious history, textual transmission, linguistic changes, and cultural interaction.