The Celts really originate from a complex and unsettled past rooted in the Indo-European linguistic family. Scholars have yet to agree on a precise origin, and evidence challenges traditional views. The Proto-Celtic language and culture likely emerged through interactions among diverse Bronze and Iron Age groups across Europe.

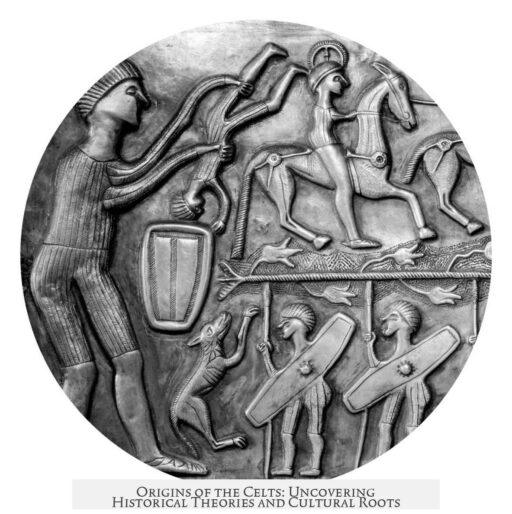

The most common theory linked the Celts to the Hallstatt (800–500 BCE) and La Tène (500–1 BCE) cultures located in Central Europe. These archaeological cultures were once thought to represent the early Celtic homeland, associating known Celtic-speaking groups such as the Gauls and Celtiberians with this origin. Hallstatt’s material culture, including iron weaponry and fortifications, spread from the Alpine region to areas like Gaul, Britain, Spain, Italy, and the Balkans. However, this theory faces significant criticism.

Artifacts associated with La Tène appearing in western regions like the British Isles often seem imported or locally adapted rather than indicating mass migrations. Additionally, linguistic research complicates the picture. Primitive Irish and Celtiberian, earlier thought closely related within ‘Q-Celtic,’ do not form a clear-cut linguistic group separate from Gaulish and Brittonic (Insular Celtic languages). This suggests a more complex spread of Celtic languages than a straightforward movement from Hallstatt-La Tène heartlands.

Because of these complexities, the Hallstatt-La Tène paradigm no longer fully explains Proto-Celtic origins. It is now viewed more as marking a diffusion of Celtic cultural traits rather than the birthplace of the Celtic language family.

Bronze Age cultures prior to Hallstatt, especially the Urnfield culture (1200–800 BCE), offer alternative frameworks. Urnfield culture expanded over large swaths of Europe, overlapping with later Celtic-speaking regions except western Gaul, much of Spain, and the British Isles. Urnfield populations participated in a broad cultural horizon characterized by cremation urns, bronze weapons, and fortified villages.

Within Urnfield, multiple linguistic groups likely coexisted. These included proto-Celtic, proto-Italic, proto-Germanic, and possibly a non-Indo-European ‘North-West Block’ centered on the Netherlands. The North-Alpine region acted as a dynamic hub, intermittently expanding and contracting, facilitating the spread of Proto-Celtic languages and culture along trade and migration routes. This framework suggests a diffuse, networked origin of Celtic languages rather than a single point of emergence.

Tracing further back, earlier Bronze Age complexes such as Tumulus (1600–1200 BCE) and Unetice (2300–1700 BCE) add layers of material and genetic continuity pre-dating the Proto-Celtic stage. The Globular Amphorae culture, once linked to early Celtic origins by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, instead seems related to Old European populations that Indo-Europeanized but did not directly contribute to Celtic languages.

The Bell-Beaker horizon (2800–1800 BCE) signals significant demographic shifts in western Europe. This culture introduced newcomers from the steppe, replacing older populations and spreading Indo-European languages. The Bell-Beaker peoples probably spoke a form of post-Proto-Indo-European, a broader language grouping sometimes called ‘North Western Indo-European.’ This ensemble likely gave rise to proto-Celtic, proto-Italic, and proto-Germanic branches.

Recent linguistic research highlights a provocative alternative: a Celtic origin centered in central Spain before 800 BCE, known as Celtiberia. Deciphered inscriptions on stone slabs in southwestern Spain and Portugal reveal a pre-Celtic Indo-European language using the Phoenician alphabet. This language likely arrived by sea from the eastern Mediterranean, spreading inland and mixing with non-Indo-European Iberian populations. The resulting ancient K/Q Celtic expanded northward.

K/Q Celtic is the form found in Irish Gaelic. While ancient insular Celtic languages started as K/Q Celtic, in Britain, a later shift created P-Celtic languages such as Brittonic. This ‘From the West’ theory proposes Celtiberians disseminated culture along the Atlantic coast to Britain and France, influencing Hallstatt Celts who then pushed P-Celtic westward.

However, the ‘From the West’ hypothesis remains debated, mainly due to lack of strong evidence for eastward cultural spread across France. Natural barriers like the Pyrenees, the presence of Basques, and Iberian populations make large-scale eastward migrations improbable. Thus, the linguistic geography may result from complex interactions rather than single directional movements.

| Theories on Celtic Origin | Main Features | Critiques |

|---|---|---|

| Hallstatt-La Tène Theory | Proto-Celtic arises in Central Europe (800–1 BCE); linked to material cultures and migrations | Artifacts in western regions may be imports; linguistic evidence inconsistent; criticized since mid-20th century |

| Urnfield Culture Hypothesis | Bronze Age (1200–800 BCE) shared culture; multiple linguistic groups; diffusion via networks | Not all Urnfield speakers are Celtic; complex overlapping groups complicate direct link |

| Bell-Beaker Horizon | Steppe migrations (2800–1800 BCE); spread Indo-European languages; ‘North Western Indo-European’ umbrella | Language forms broad; exact Celtic emergence uncertain within group |

| Iberian/Celtiberian Hypothesis | Central Spain pre-800 BCE; sea migration from Mediterranean; mixing with Iberians; K/Q Celtic origin | Lack of evidence for eastward spread; challenges traditional diffusion models |

Important scholars include John Koch, who supports the ‘From the West’ theory; Eduard Selleslagh-Suykens, proposing Iberian sea route origins; Henri Hubert, who cautioned conflating La Tène culture with Celts; and James Patrick Mallory, who conceptualized ‘North Western Indo-European’ linguistic origins.

The Celtic origin question remains open, reflecting complex cultural and linguistic interactions spanning millennia. Current consensus rejects a simple birthplace model in favor of multi-regional developments linked through migratory and trade networks.

- Celtic origins link to Indo-European language diffusion but lack a consensus birthplace.

- Traditional Hallstatt-La Tène model is outdated due to archaeological and linguistic complexity.

- Bronze Age Urnfield culture forms a key cultural horizon with diverse linguistic groups.

- Earlier Bell-Beaker migrations introduced Indo-European languages to western Europe.

- New evidence suggests a Celtic origin in Iberian Peninsula, involving maritime migration and language mixing.

- Complex language evolution includes K/Q and P Celtic branches reflecting separate developments.

- Scholars stress networked diffusion of culture and language instead of violent mass migrations.

Where Did the Celts REALLY Originate From? The Mystery Unfolds

So, where did the Celts really come from? The short answer: nobody knows for sure. Despite centuries of digging, analyzing, and theorizing, historians and linguists still debate the true birthplace of the Celts. Before grabbing your sword and hoplite helmet, let’s unravel the story behind this ancient puzzle—because the truth is far more exciting and less straightforward than popular tales suggest.

The Indo-European Puzzle and Proto-Celtic Mysteries

The Celts are part of the broad Indo-European family, a huge linguistic clan speaking related languages scattered over Europe and parts of Asia. Scholars agree Celtic languages belong here, but pinpointing exactly when and where Proto-Celtic—the ancestor language—broke away from the common Indo-European tree? That’s the real head-scratcher.

Imagine a massive family reunion where everyone speaks similar but distinct dialects. Which dialect turned into Celtic? Which was just a guest? No one has a firm date, and our clues come mainly from archaeological finds and fragmentary languages that barely survived the millennia.

Traditional Theory: Hallstatt and La Tène Cultures

For decades, archaeologists pointed to the Iron Age Hallstatt (800-500 BCE) and La Tène (500-1 BCE) cultures centered in Central Europe. These material cultures—what people left behind like pottery, weapons, and settlements—were long believed to mark where the Celts originated.

From the Alpine regions, the Hallstatt-La Tène folks supposedly spread out violently to western Gaul, Spain, Britain, and even the Balkans. But here’s the twist: artifacts bearing Hallstatt and La Tène styles in distant places, like the British Isles, look more like imports or local adaptations rather than direct evidence of mass migrations.

Henri Hubert, a pioneer of Celtic studies, warned as early as the 1940s and 50s not to simplistically equate La Tène culture with Celtic peoples—a warning modern science takes seriously.

New linguistic studies complicate things further. Primitive Irish and Celtiberian were once lumped together in the “Q-Celtic” group. However, more recent understanding shows Irish (Goidelic) and Brittonic languages are closer cousins to Gaulish than previously thought—a tangled Celtic family tree indeed.

Moreover, Lepontic—a Celtic language attested in northern Italy during the Late Bronze Age—does not fit well with a simple Hallstatt-origin migration from Central Europe. These challenges mean this Central European theory, popular in textbooks and museums, no longer holds as a definitive origin story.

Urnfield Culture: The Bronze Age Background

Digging deeper into the Bronze Age reveals the Urnfield culture (1200-800 BCE) as a possible candidate for Proto-Celtic origins. Urnfield covered a huge region—overlapping with Hallstatt areas—stretching from central Europe but missing parts like western Gaul, Spain, and the British Isles.

This culture wasn’t a one-language show. It likely hosted multiple linguistic groups: proto-Celtic, proto-Germanic, proto-Italic, and even the mysterious ‘North-West Block’ in the modern Netherlands. They shared customs, like cremation urn burials and skilled bronze weapons, signaling a common cultural horizon with complex social networks.

The North-Alpine region acted like a nerve center, pulsing and radiating influence, possibly triggering migrations to places like Spain during the Late Bronze Age. Think of it as an ancient superhighway for cultural and linguistic traffic.

Earlier Cultures: Tumulus, Unetice, and Globular Amphorae

Seeking even older roots leads to Tumulus culture (1600-1200 BCE) and Unetice culture (2300-1700 BCE). They form a chain of material and genetic continuity before Proto-Celtic emerged, but give us no clear proof of Celtic origins themselves.

The Globular Amphorae culture was once considered deeply linked to Celtic as per Marija Gimbutas, a famous archaeologist. However, current genetics tie it more to Old European populations that became Indo-Europeanized without direct Celtic connections. So close, but no cigar.

Bell-Beaker Phenomenon and Indo-European Spread

Imagine waves of new people arriving in Western Europe from the steppes, reshaping demographics between 2800-1800 BCE. This is the Bell-Beaker horizon, widely associated with Indo-European spread that affected the entire continent, including Iberia.

These newcomers spoke a mix: post Proto-Indo-European languages mingling with remnants of non-Indo-European tongues. James Patrick Mallory calls this melting pot “North Western Indo-European,” the linguistic crucible from which branches like Proto-Celtic—and others—emerged.

The Iberian Hypothesis: New Linguistic Turns

Here’s a fresh twist: recent linguists are pointing to Central Spain—Celtiberia—as the cradle of Celtic languages before 800 BCE. Stone slabs inscribed in the Phoenician alphabet found in southwestern Spain and Portugal show a pre-Celtic Indo-European language.

Scholars like Eduard Selleslagh-Suykens propose this language arrived by sea from the eastern Mediterranean, not over hills from Central Europe. The settlers mingled with local Iberian peoples, creating ancient K/Q Celtic—an ancestor of Irish Gaelic and other Insular Celtic languages.

This scenario flips the traditional “East-to-West” model, suggesting instead a “From the West” theory. Celtiberians expanded along the Atlantic coast into Britain and eastward into France, influencing Hallstatt Celts who spoke P-Celtic dialects.

But the “From the West” theory faces hurdles. There’s scant evidence that Celtic languages spread eastward across tough barriers like the Pyrenees mountains or amongst resistant populations such as the Basques and Iberians. So, the Celtiberian spread north is plausible but not fully proven.

Scholarly Voices Worth Mentioning

- John Koch champions the “Celt from the West” thesis.

- Eduard Selleslagh-Suykens advocates proto-Celtic development in Spain via seaborne migrations from the Adriatic coast.

- Henri Hubert provides early cautionary advice resisting simplistic identifications of culture and language—particularly regarding La Tène equals Celt.

- James Patrick Mallory lays out the “North-Western Indo-European” linguistic framework, a crucial starting point for Celtic roots.

So, What Now? The Ongoing Celtic Quest

In summary, declaring a single “homeland” of the Celts oversimplifies a long, complex evolution. The traditional Central European Hallstatt-La Tène cradle is giving way to broader views spanning Bronze Age Urnfield networks, earlier cultural layers, and exciting evidence in Iberia.

The Celts likely formed not in one flash but as a wave of related dialects and cultural trends interacting over centuries and regions. There’s evidence for seaborne movements bringing Indo-European languages into Spain, mixing with local languages to grow Proto-Celtic, and expanding north and westward through Europe.

Could the Celts originally be Spaniards turned travelers influencing peoples across the Atlantic coasts? Possibly. Or maybe they’re a shuffled blend of Central European and Mediterranean influences together forging the languages and customs we call Celtic today.

What’s clear is that Celtic origins are a riveting story without a neat ending—perfect for those who love history with a twist. So, the next time someone claims the Celts “originated” somewhere specific, ask them: “Which Celts, exactly? And from which century?” History rarely deals in simple answers.

Want to Dive Deeper?

For those itching for adventure down Celtic lanes, exploring these cultures through museum exhibits or scholarly resources is rewarding. Look out for Urnfield cremation urns, Bell-Beaker pots, or inscribed Celtiberian stones. Each artifact whispers a bit more about our enigmatic ancestors.

And remember, in Celtic studies—and life—it’s often the journey, not just the destination, that tells the best story.