The historical and historiographical status of “No Irish Need Apply” (NINA) shows that while such signs and ads did exist, they were rare rather than widespread. The phenomenon became more of a cultural symbol and a persistent cultural myth than a reflection of common, overt discrimination found in employment postings. The debate about NINA centers not on its existence but on its frequency, cultural impact, and the nuances of anti-Irish discrimination in different contexts.

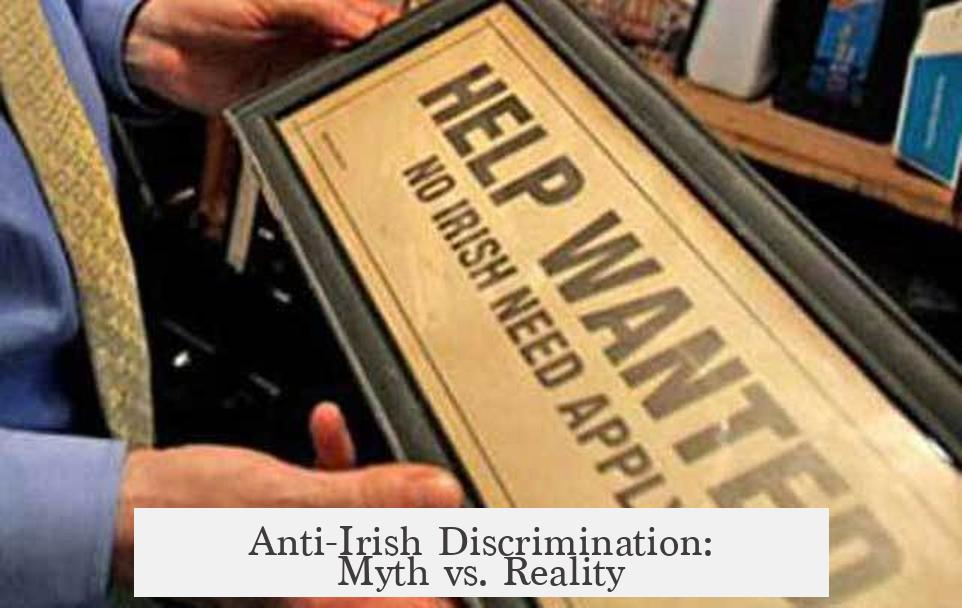

The existence of “No Irish Need Apply” ads and signs is well documented. Such advertisements appeared in newspapers and occasionally as physical signs in places across the United States and the United Kingdom. Detractors who deny their existence often overlook documented cases from the 19th century. Indeed, scholars like Master Skeptic Jensen acknowledge that NINA signs existed and were real, especially appearing between 1842 and 1869.

However, the intense focus on counting and confirming the frequency of these ads risks distorting the bigger picture. Concentrating solely on disproving or confirming the presence of NINA ads tends to ignore the broader cultural environment of anti-Irish sentiment. Treating NINA solely as a factual artifact neglects the cultural significance and the social conversations that made the phrase a recognizable buzzword on both sides of the Atlantic.

NINA’s cultural footprint appears more powerful than the actual numbers of discriminatory ads might suggest. Jensen’s research finds the ads to be rare, possibly so infrequent that an average literate person in an Irish-heavy American city might never encounter one directly in their lifetime. Yet the phrase carried weight in popular songs, letters, and journalism, suggesting that the anti-Irish prejudice it symbolized permeated cultural consciousness, even if formal recorded instances of exclusion via signage or advertisements were uncommon.

Academic critiques of Jensen’s work highlight key methodological issues. His research depends heavily on digital archives of upscale newspapers such as The New York Times and The Nation, which catered to a more affluent, less labor-focused audience. Critics like Fried argue this sampling bias excludes populist papers like the New York Sun, which were more likely to be read by Irish immigrant workers and might have contained more examples of NINA.

Fried’s criticism extends to Jensen’s exclusion of female employment in the analysis. Many NINA ads targeted female domestic workers, specifying requirements like “No Irish need apply” or “Protestant only” in advertisements for nannies, maids, cooks, and nurses. Overlooking these ads paints an incomplete picture of discrimination, given domestic service was a significant source of employment for Irish immigrant women.

Existing NINA ads and references span nearly a century but remain relatively few in number. The total identified references—around 69—over nearly 100 years are scattered, with more than half appearing before 1870. These data underscore the rarity of NINA postings rather than widespread, formalized exclusion. Importantly, the myth of NINA is frequently focused on physical signs, but surviving evidence includes mostly newspaper ads and anecdotal accounts.

Ultimately, the debate clarifies that anti-Irish discrimination was real but complex. It manifested more in social prejudices, political exclusion (especially anti-Catholicism), and unrecorded practices than through a widespread, standardized signage campaign in employment contexts. Discrimination did impact Irish immigrants but not necessarily in the overt “No Irish Need Apply” manner popularly imagined.

Modern historiography acknowledges the existence of NINA while placing it in a broader context of immigrant discrimination, ethnic stereotyping, and cultural memory. This balanced view recognizes that:

- NINA ads existed but were not widespread or common.

- The cultural significance of NINA lies more in its symbolic power than frequency.

- Research methods affect our understanding due to biases in archival sources.

- Anti-Irish discrimination varied by gender, occupation, and location.

- The mythologizing of NINA reflects broader social dynamics and immigrant experiences.

This nuanced understanding builds a more accurate picture of Irish immigrant acceptance and resistance in 19th-century Anglo-American societies. It also emphasizes the role cultural memory can play in shaping historical narratives beyond strictly empirical evidence.

Key Takeaways:

- “No Irish Need Apply” signs and ads existed but were rare.

- The phrase became a powerful cultural symbol more than a common labor market reality.

- Studies vary due to methodological biases and sample limitations.

- Anti-Irish discrimination was real but often took subtler or different forms than overt job exclusion signs.

- Excluding female-targeted ads overlooks an important dimension of workplace discrimination.

Where Are We on “No Irish Need Apply,” Historically and Historiographically Speaking?

The phrase “No Irish Need Apply” (NINA) certainly existed. That’s the starting point. These signs and ads weren’t just urban legends or awkward jokes whispered over pints—they were part of a real historical fabric. Skepticism about their existence dates back, but the evidence confirms they showed up. Not exactly a flood, but notable nonetheless.

But the key to understanding NINA lies beyond just proving it existed. The conversation is richer, stretching into culture, identity, and historical nuance. The real question becomes: How common were these signs and what did they mean? Let’s unpack this carefully.

The Existence and Prevalence Debate

First, claiming NINA ads didn’t exist at all is a dead end. Master Skeptic Jensen knows better, as do historians who’ve examined newspaper archives and physical signs. Yet, focusing solely on the presence or absence of such signs misses the broader point—and here’s the kicker—it’s a quite sexist and misleading frame to limit the discussion to male-oriented job ads.

Why sexist? Because many NINA ads targeted women in domestic service roles. Newspapers specify “Protestant only” or “No Irish need apply” explicitly in ads seeking cooks, maids, nurses, and nannies. One 1868 Brookline ad sought a woman, “to take the care of a boy two years old,” with a strict “positively no Irish need apply” stipulation. This reinforces the idea that NINA was not only a male labor market issue but also a cultural expression of ethnic-based sexism and discrimination affecting women.

NINA, in that exact phrasing, became a cultural buzzword. It wasn’t just signs or classified ads; the phrase appeared in songs, letters, and journalism on both sides of the Atlantic. This suggests a shared societal awareness of the discrimination that the phrase signified. It functioned more as a symbol of anti-Irish sentiment rather than a sign people saw every day plastered on every hiring post.

Jensen’s claim that the actual printed NINA signs and ads were rare but not unheard of stands firm. According to his findings, in many Irish-heavy cities, a literate person statistically might never encounter such an ad in a lifetime. Rarity, however, does not diminish the cultural impact. The myth—the cultural memory—sometimes looms larger than the actual physical presence.

Jensen vs. Fried: The Academic Showdown

History evolves with debate, and in this case, the contest between Jensen and Fried illuminates how historiography shapes our view of NINA.

Jensen’s research—though pioneering—had limitations. He scanned digital newspaper archives but acknowledged limited numerical coverage. This is important because the newspapers he analyzed skewed upscale—think New York Times and The Nation.

Fried countered effectively. She argued those kinds of papers weren’t the ones Irish immigrants most likely read. Irish temp workers probably grabbed their local populist papers, like the New York Sun, which Jensen’s digital databases missed. By ignoring this gap in audience and source, Jensen’s conclusions risk missing a significant slice of the NINA phenomenon.

Academic historians face intense pressure to publish novel conclusions. This drive can encourage drawing grand claims from incomplete evidence—you could call it “publish or perish,” but the side effect is the temptation to overstate findings. Journals, after all, rely on article downloads, part of a $25.2 billion industry, so exciting claims grab eyeballs and funding.

Fried is also guilty of some selective omission—both scholars sidestep extensive discussion on NINA’s impact on women’s employment, despite ample evidence of female-focused discrimination ads. Fried’s own appendix quotes many ads targeting men explicitly or ambiguously, but ignoring the gendered nuance here weakens the conversation.

The Sexist Assumption and Women in the NINA Story

It’s tempting to think the infamous “No Irish Need Apply” was only about men getting shut out of labor. Wrong. The earliest known uses of NINA were connected to women’s domestic servant positions.

This is essential because historically, much of the Irish immigrant women worked as domestic servants. Their jobs were often the first available economic opportunities. The ads revealing preferences or exclusions based on ethnicity or religion explicitly show that NINA was a wider societal phenomenon.

The assumption that ads targeting women weren’t influential or did not contribute to the cultural “meme” of discrimination is, frankly, sexist bad history. The entire meme probably drew power from both male and female experiences, facilitating a broader societal climate of ethnic discrimination.

What About the Physical Signs vs. Newspaper Ads?

Physical signs saying “No Irish Need Apply” are part of the story but aren’t the full picture. Researchers tallying references uncovered about 69 instances across a century-long timeframe, with physical signs being a tiny fraction (only one to three). The rest mostly appeared in newspaper ads spanning the U.S., especially from 1842 to 1869.

This distinction matters. Newspaper ads leave a better documentary trail than physical signs. Yet, the societal reaction focused disproportionately on signs, possibly because signs are more visible and tangible. People react emotionally to a sign on a storefront rather than a tiny classified ad buried in newsprint. But even if the physical signs were uncommon, the ads and cultural conversation reveal a widespread anti-Irish sentiment.

Anti-Irish Discrimination: Myth vs. Reality

Jensen’s broader thesis suggests that anti-Irish discrimination, at least for males, wasn’t as pervasive in American labor markets as legend says. He concedes more discrimination occurred in female labor markets and that anti-Catholic bias remained strong in politics and public life well into the 20th century.

This layered reality challenges simplified narratives and exposes complexity. The myth of pervasive NINA signs captures a powerful emotional truth of exclusion but doesn’t translate neatly into quantitative reality. Discrimination was real, but it wasn’t always expressed through the specific “No Irish Need Apply” signs we picture in our minds.

Why Does This Matter Today?

So, where are we now, historiographically? We stand at a crossroads of myth and fact, cultural memory and archival record.

This nuanced perspective reminds us history isn’t always black and white. It’s a mosaic. Yes, signs existed. Yes, discrimination was real. But the phrase “No Irish Need Apply” also became a cultural code, a shorthand representing broader social exclusion Irish immigrants faced. Its rarity doesn’t negate its power.

Understanding this history also challenges us to think critically about how narratives get shaped. Are certain stories amplified because they fit a neat victimization narrative? Do we sometimes miss gender or class nuances because of laziness or bias?

Reflecting on NINA’s historiography encourages deeper questions: How do communities remember discrimination? What counts as evidence in history? And how does academic pressure shape our stories?

What Can We Learn and Do?

- Look beyond the headline: Don’t judge the scale of historical discrimination purely by the frequency of signs or ads.

- Value cultural memory: Even rare evidence can illuminate widespread social attitudes and prejudices.

- Recognize gender and class roles: The NINA story isn’t just about men competing for factory jobs; it includes women laboring as domestic servants facing explicit exclusion.

- Understand historiographical debate: Appreciate that history is a dynamic dialogue among scholars, not a final verdict.

- Think critically about sources: Whose voices read newspapers? What archives survive? Knowing this prevents skewed interpretations.

So next time you hear “No Irish Need Apply,” remember it’s not just a sign or an ad from the past. It’s a keyhole into a messy, complicated story about immigration, discrimination, resilience, and how we tell history itself.

What is the current consensus on the existence of “No Irish Need Apply” signs?

These signs did exist, though they were rare. It’s clear they were not as common as the cultural story suggests. Their presence is confirmed but limited in frequency.

Why is focusing only on male-oriented NINA ads misleading?

Focusing solely on male job ads ignores significant evidence from female employment. Many NINA instances targeted women, especially domestic servants, which broadens understanding of discrimination.

How do historians explain the strong cultural memory of NINA despite its rarity?

The phrase became a cultural buzzword. It represented a well-known anti-Irish sentiment in songs, letters, and journalism, maintaining its power beyond the actual number of ads.

What are the main critiques of Jensen’s research on NINA?

Jensen’s archive scan was limited and biased toward upscale newspapers, missing more populist sources favored by Irish laborers. This may understate the presence of NINA ads and signs.

How did NINA discrimination manifest differently for women?

NINA ads targeting women often appeared in domestic servant job postings. These ads sometimes explicitly excluded Irish women, revealing a gendered dimension to anti-Irish discrimination.