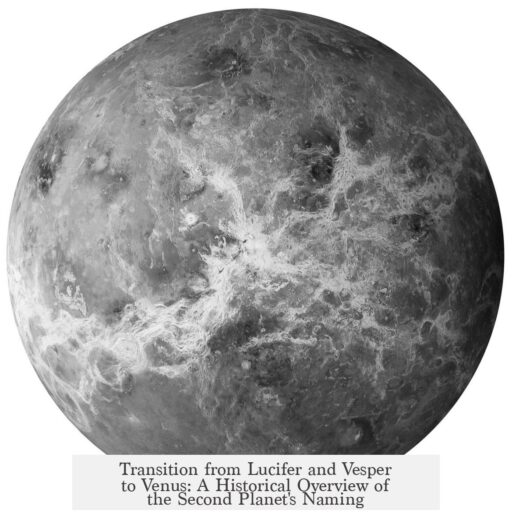

Western astronomers began consistently using the name Venus for the second planet gradually from antiquity, favoring it over the alternative names Lucifer and Vesper, which appeared mainly in poetic and less formal contexts.

The planet known today as Venus was named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty, equivalent to the Greek goddess Aphrodite. Hellenistic astronomers commonly used the name Aphroditē or the phrase “astēr Aphroditēs” (star of Aphrodite) from the 4th century BCE onward. This tradition continued as Roman culture adopted the goddess Venus as the planet’s namesake.

The names Lucifer and Vesper, Latin terms meaning “light-bringer” and “evening star,” originated from a later astronomical naming system based on brightness and shine. This “shiny” nomenclature also gave Mercury the name Scintillans and Mars the name Rutilus. However, this system coexisted with the older, divine-based naming conventions and never fully replaced them.

Lucifer referred specifically to Venus as the “morning star,” while Vesper meant “evening star.” Poets and writers frequently used these terms to evoke imagery but did not establish them as formal astronomical names. The use of Lucifer and Vesper did not overtake Venus as the primary name for the planet in scholarly astronomy.

By the 1st century CE, the naming conventions of the weekdays provide clear evidence of Venus being the dominant name for the planet. For example, the day Friday was called “the day of Venus/Aphrodite,” without any reference to it being the “day of the star of Venus.” This indicates that the simpler and divine-based name Venus was standard in public and scholarly usage.

By the late antiquity period, around the 400s CE, Martianus Capella, a notable Latin writer, lists the classical planets as Saturnus, Iuppiter, Mars, Mercurius, and Venus. Significantly, he omits any qualifier like “star of,” which suggests the names had become fixed in their simpler divine forms. This further supports the steady preference for Venus over Lucifer or Vesper in formal astronomy.

No single event or specific date marks the definitive shift from using Lucifer or Vesper to calling the planet Venus exclusively. Instead, historical records show that both naming traditions coexisted during most of antiquity. Different authors and cultures might prefer one over another depending on context.

Official planet names, as recognized today, remained fluid until modern times. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) did not formalize planet nomenclature until the 20th century, long after these traditional names had been in scholarly and popular use.

- The oldest classical name for the planet is based on the goddess Aphrodite (Greek) or Venus (Roman).

- Lucifer and Vesper emerged as poetic, brightness-based alternatives but were never dominant.

- By the 1st century CE, Venus was already the preferred name, as seen in weekday naming.

- Martianus Capella’s writings in the 400s CE confirm the standard use of Venus.

- No exact transition date exists; the shift was gradual and traditional.

- Formal planetary naming only occurred centuries later with the IAU.

This nuanced background explains why Western astronomers eventually standardized “Venus” as the second planet’s name while Lucifer and Vesper remained largely literary or poetic labels rather than scientific terms.

When Did Western Astronomers Start Calling the Second Planet Venus Instead of Lucifer or Vesper?

The simple answer: Western astronomers started calling the second planet Venus—not Lucifer or Vesper—pretty much from antiquity onward, with the names Lucifer and Vesper serving as poetic or descriptive epithets rather than official planetary names.

Now, you might wonder: Why the mix-up between these names at all? And why do we even hear about Lucifer or Vesper for Venus? Let’s dig into the rather sparkling history of how this luminous celestial body got—and kept—its spot as Venus.

Venus in the Ancient World: A Name With Roots

Contrary to what some might think, there were no official “planet names” like we have today until the International Astronomical Union (IAU) standardized them in the 20th century. In fact, until then, names varied based on culture, language, and even poetic flair.

For the Greeks, the second planet was almost always called Aphrodite or astēr Aphroditēs—which translates neatly to “star of Aphrodite.” This practice dates back to at least the 4th century BCE, as demonstrated by Aristotle’s metaphysics texts, where the planet is simply called “Aphrodite,” no fuss about being “star of” anything.

You might expect some grand shift from “star of Aphrodite” to “Aphrodite,” but in reality, both versions coexisted for centuries. Even in the 400s CE, Martianus Capella referenced the planets straightforwardly as Saturnus, Iuppiter, Mars, Mercurius, and Venus, dropping any “star of” prefixes entirely. The old and the new happily mingled throughout the Greco-Roman world.

So Where Do Lucifer and Vesper Fit In?

Enter the alternate “shiny” naming system. This scheme, appearing later than the divine names, labeled planets based on brilliance:

- Phōsphoros (Greek for “light-bringer”) and Lucifer (Latin for “light-bearer”) both served as names for the morning appearance of Venus.

- Vesper corresponds to its evening star persona, used more in poetic descriptions.

This “shiny” nomenclature system never actually replaced the older divine system. They lived side by side, with scholars like Martianus Capella even providing translation lists between the two. So, while Lucifer pops up as a name for Venus in Latin texts, it was never the formal planetary name but more a descriptor of the bright beauty seen at dawn.

Multiple Names: The Morning and Evening Star Confusion

Interestingly, Homer’s Iliad uses not just two, but three names associated with Venus: Eōsphoros (“dawn bringer”), Hesperos (“evening star”), and Ēōios (“dawn star”). This demonstrates that ancient storytellers, and perhaps early astronomers, recognized the planet in both its morning and evening resplendence, albeit under poetic aliases.

But—here’s a curveball—the Greeks actually knew **Venus is a single planet** by around the 500s BCE, if not earlier. The different names reflected how it appeared at various times of day, not separate planets. Today, we still say “morning star” or “evening star,” but everyone knows it’s Venus shining bright. This archaic linguistic quirk remains part of our cultural vocabulary.

Aphrodite Is Not a Borrowed Name

Some have claimed that Aphrodite’s cult was borrowed from the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, suggesting the name and worship “migrated” into Greece. This is a misconception. Aphrodite is a native Greek deity. What did happen—common in ancient understandings of gods—is interpretatio graeca, where Greeks equated foreign gods with their own—like translating divine names respectfully without losing cultural identity.

Various “Lucifers” and Who They Were

It’s worth clarifying a popular confusion: the name Lucifer in classical astronomy simply meant “light-bringer” in Latin. It specifically referred to Venus when visible in the morning sky. It had no devilish connotations back then. The negative modern associations with the name come much later and from religious texts, not from ancient astronomy.

Similarly, Vesper denotes the evening manifestation of Venus and is mostly poetic. Occasionally, one might come across this name in Latin writings or Renaissance literature, but it doesn’t appear as a formal planet name in scientific contexts.

What Does This Mean Today?

So why do we call this blazing planet Venus now, and when did it become exclusive?

The use of “Venus” became dominant in Western culture through the Roman adoption of Greek gods. Roman astronomers and poets favored using the feminine divine name Venus derived from their goddess of love and beauty, maintaining consistency and clarity. The poetic “Lucifer” and “Vesper” remained just that—poetic names for different views of the same brilliant orb.

By late antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages, the divine name Venus was established firmly for the planet we all know today. The alternate names did not persist as scientific terms. The Renaissance and later astronomers used “Venus” in line with tradition, cementing it as the official name before the modern era’s standardizations.

Takeaway for the Curious Skywatcher

Next time you spot the glowing evening or morning star, remember: You’re gazing at a planet called Venus—a name stretching back thousands of years and rooted in love and beauty, not just brightness or poetic fancy.

“Lucifer” still shines, quietly, as the morning star’s ancient nickname, but if you want to avoid confusion—especially with modern culture—stick with Venus, the timeless name.

Practical Tip for Astronomy Buffs

If you read ancient texts or enjoy classical poetry, watch for these different names. They offer fascinating insights into how the ancients experienced the sky differently—more poetically, with reverence and imagination. This deepens your understanding of how language, culture, and science entwined in their observations of the heavens.

In short: Western astronomers didn’t suddenly ditch Lucifer or Vesper for Venus in a seismic renaming event. Instead, Venus was always the central name harkening back to mythology, while the other labels were poetic flourishes or descriptive nicknames never meant to replace the goddess’s name.