Swords and armored knights became militarily obsolete by the early to mid-20th century, with the last regular military uses of swords fading during and shortly after World War II, while full plate armor declined significantly from the 16th century onward due to advancements in weaponry.

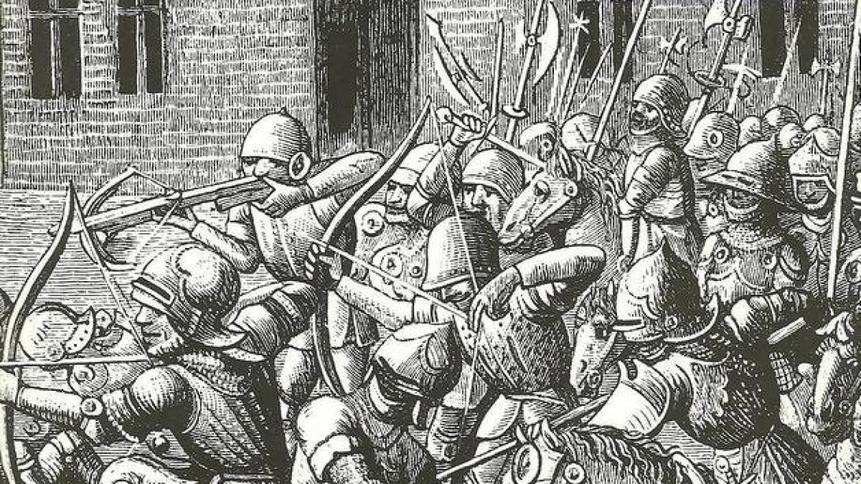

The evolution of weapons and tactics dictated the decline of swords and armored knights. By the 15th century, plate armor reached a peak that rendered traditional swords ineffective for killing heavily armored knights. To bypass plate armor, warriors favored weapons like polearms, war maces, fighting picks, and axes designed to concentrate force or pierce armor. Swords became less practical for frontline combat against well-armored foes.

Despite this, swords remained a part of military culture for centuries. The Swedish Carolean army equipped infantry with rapiers, and infantry hangers were common sidearms through the 18th and 19th centuries. By the late 19th century, these were replaced largely by fascine knives, tools blending characteristics of swords and machetes.

Cavalry maintained the use of sabres longer than infantry did. They remained standard issue on horseback until about the end of World War II. The British cavalry, for example, used swords until its transition to armored vehicles in 1938.

World War I marked a final major point for swords in military use. Infantry officers of all combatant nations carried swords early in the conflict. However, the impracticality of swords in trench warfare led to their rapid discontinuation within weeks. Some cavalry units and officers still carried swords into World War II but these were largely ceremonial or symbolic; firearms had decisively replaced melee weapons.

The British boarding action on the German freighter Altmark in 1940 serves as probably the last use “in anger” of swords by a regular military force. British sailors used cutlasses during the operation, marking one of the very last combat instances of swords in modern warfare.

Swords have persisted in many militaries but now only as ceremonial items. For example, U.S. Marine Corps officers and non-commissioned officers carry ceremonial swords on formal occasions. This preservation honors tradition and heritage rather than practical combat utility.

Plate armor’s decline closely followed the rise of gunpowder firearms. While 15th-century plate armor was highly effective versus arrows and melee weapons, the English longbow had already demonstrated its ability to penetrate armor during the Hundred Years’ War. The growing power and accuracy of firearms made full-body plate armor too heavy and expensive to be practical.

Elite cavalry units like the Imperial Cuirassiers in the Thirty Years’ War or Polish Winged Hussars continued to wear partial armor such as cuirasses and helmets well into the 17th and 18th centuries. These offered vital protection against cavalry swords, pikes, and pistols. Some cavalry maintained cuirass and helmet use as late as World War I. Infantry abandoned large-scale armor use much earlier.

Technological improvements favored lightly armored or unarmored riflemen and bowmen over heavily armored knights. Firearms could penetrate all but the thickest armor, pushing armies to adopt cheaper, more mobile troops.

Broader definitions of warfare reveal that swords have not vanished entirely. In tribal and paramilitary conflicts, especially in underdeveloped regions, bladed weapons retain relevance. During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, machetes—which can loosely be classified as swords or large knives—were brutally used in mass killings. This grim example shows how blades can remain potent tools of terror and violence long after losing battlefield prominence.

In short, swords and armored knights ceased to be effective military forces by the early 20th century, displaced by firearms and changes in combat strategy. Yet, they survive ceremonially and persist among irregular or tribal conflicts worldwide.

| Item | Date Range | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Plate Armor Decline | 16th Century onward | Fell out of favor due to firearm penetration and heaviness |

| Last Infantry Military Sword Use | Early 20th Century (WWI) | Officers carried swords; declined weeks into WWI |

| Last Military Sword Use in Combat | 1940 | HMS Cossack cutlasses in Altmark boarding |

| Cavalry Sabres in Use | Until WWII (1938-1945) | British cavalry used swords until mechanization |

| Plate Armor on Cavalry | Up to WWI | Partial protection with cuirasses and helmets |

| Ceremonial Use | Present Day | Military and ceremonial swords remain in armies worldwide |

- Swords became obsolete as frontline weapons by mid-20th century.

- Plate armor declined starting in the 16th century due to firearms.

- Cavalry retained swords and partial armor longest.

- Firearms made swords and full armor impractical.

- Swords survive ceremonially in modern militaries.

- Swords or machete-like blades remain relevant in irregular or tribal conflicts.

When Did Swords and Armored Knights Become Obsolete?

The obsolescence of swords and armored knights didn’t happen overnight—it was a slow fade marked by shifts in technology, warfare tactics, and societal changes. So, when did swords and armored knights become obsolete? The answer lies in the gradual evolution of weaponry and military needs, reaching key turning points from the 15th century through the second half of the 20th century.

Let’s take a walk through history to uncover how and when swords and armored knights bowed out of frontline battle roles, and why they sometimes still make cameo appearances today.

The Decline of Armored Knights: Why Plate Armor Lost Its Shine

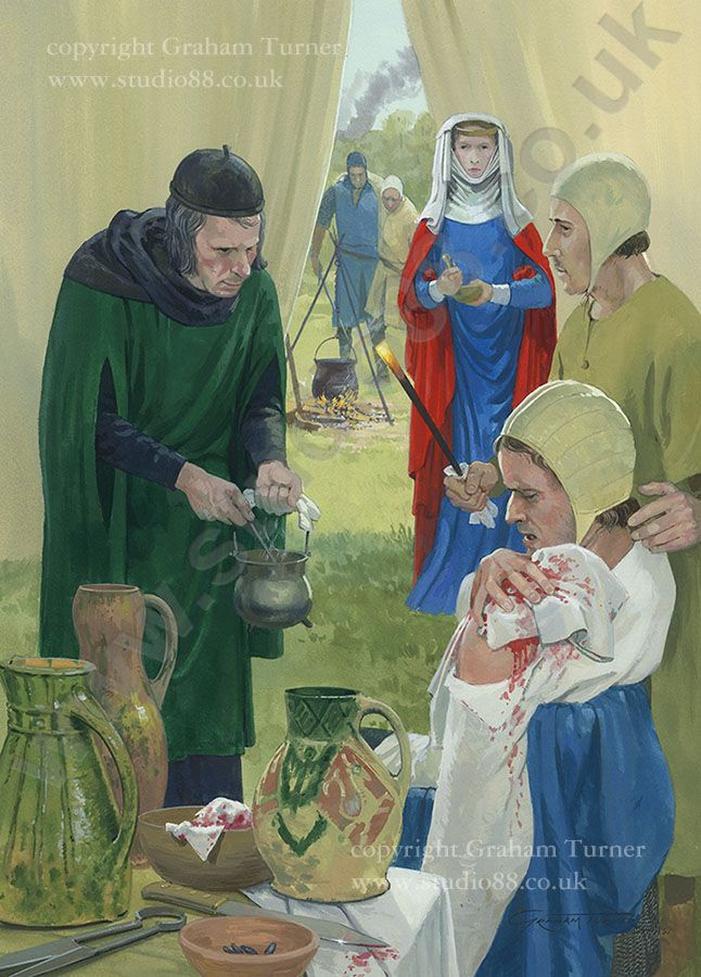

Once the epitome of battlefield dominance, plate armor started losing its practicality in the 15th century. The reason? The rise of specialized weapons designed explicitly to puncture or bypass armor. Polearms, axes, maces, and “fighting picks” (or crow’s beaks) became the weapons of choice to take down a knight in shining armor. Swords simply couldn’t compete with these heavy hitters.

What sealed the fate of armor, however, was the appearance and improvement of gunpowder weapons. As muskets and rifles became everyday tools of war, entire suits of plate armor offered little protection. They were heavy, expensive, and often ineffective against a bullet’s force.

Despite this, armor hung on with proud elite cavalry units like the Imperial Cuirassiers and the Polish Winged Hussars, who flaunted their expensive plate gear during conflicts such as the Thirty Years’ War. Even up to World War I, cavalry units sometimes suited up in cuirasses and helmets. These pieces guarded vital areas from swords, pikes, and even early pistolballs.

However, the practicality of bowmen and riflemen steadily outpaced the usefulness of expensive knights. Better ranged weaponry made the thickest armor a burden without adequate protection. By the 18th century, infantry had largely abandoned full-body armor, opting for lighter and cheaper attire. Only fragments of armor remained on cavalry units, signaling the slow but clear demise of the armored knight.

The Sword’s Final Battle: When Did It Stop Being a Military Weapon?

The sword had a long, stubborn life as a military weapon. But when did armies finally say, “Enough with the swords?”

Believe it or not, swords were still pretty common even in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Swedish Carolean army, for example, famously equipped every soldier with a rapier and an infantry hanger—a short sword-like weapon. These sidearms were standard infantry gear for a long time.

Towards the end of the 19th century, however, traditional swords like hangers began their slow slide into obsolescence. They were mostly replaced by fascine knives, which blended the line between tools and weapons—interesting hybrids of machete and short sword. This blurred the sword’s distinction but effectively ended its era as a primary weapon.

Cavalry units clung to sabres longer than most. They remained a regular part of cavalry kit well past World War I and into World War II. British cavalry, riding horses and carrying sabres, persisted until mechanized vehicles replaced them in 1938.

Even during World War I, infantry officers from all sides carried swords into battle. However, swords were quickly realized as impractical in the muddy, mechanized trenches of the Great War. Within weeks, firearms dominated, and swords faded into the background. Some officers still carried swords ceremonially into World War II, but their battlefield relevance was long gone.

Swords Today: Ceremonial Glamour or Real Weapons?

While swords are obsolete as practical weapons in most modern militaries, they’ve kept a foothold in the ceremonial world. For instance, officers and non-commissioned officers in the United States Marine Corps still carry swords on special occasions. These blades serve as symbols of tradition, honor, and pageantry, rather than combat tools.

But swords linger beyond mere showpieces. In some less affluent or conflict-ridden parts of the world, swords or sword-like weapons like machetes remain tools of terror and tribal conflict. The horrific example of the 1994 Rwandan genocide showcases how machetes were wielded as primary weapons of violence. Here, swords escape obsolescence not on battlefields but in brutal, personal, and grim circumstances.

Putting It Into Perspective: What Does “Obsolete” Really Mean?

- The military sword’s disappearance from the battlefield was gradual, spanning roughly from the 15th century (armor decline) to World War II (final military uses).

- Plate armor faded as ranged weapons advanced. Heavy armor became a liability, not a defense.

- Cavalry sabres outlived infantry swords but were retired by mechanized warfare in the mid-20th century.

- The ceremonial sword still thrives, proving that some traditions never die.

- In irregular warfare and civilian conflicts, swords or sword-like weapons continue to be effective – but under very different conditions.

So, if you ask a historian, swords and armored knights became militarily obsolete somewhere between the 17th century and World War II, depending on the context. Yet, culturally and symbolically, they stick around.

Final Thoughts: Why Should You Care?

Understanding the obsolescence of swords and armored knights isn’t just about old weapons. It shines a light on how technology shapes society, warfare, and even traditions. It also reminds us how fast innovation can make the familiar unfit for purpose.

Next time you watch a historical movie or enjoy a reenactment, remember: the shiny suits and flash of steel you see are the tip of a long story about adaptation, survival, and sometimes stubborn tradition.

“Swords and armor are not just relics; they’re milestones marking the evolution from battlefield might to modern warfare’s mechanized, ranged dominance.”

And just to satisfy your curiosity: if a boarding party on the British destroyer HMS Cossack used cutlasses to seize a German freighter in 1940, you know swords were officially hanging on by a fingernail until World War II!