Romans named some of their children after numbers primarily because these names originally corresponded to the months of the ancient Roman calendar rather than strictly to birth order. This naming practice mostly applied to males, with a few notable exceptions for females.

Originally, the Roman calendar contained ten months, beginning in March and ending in December. This calendar omitted January and February, which were added later during the regal period, long before detailed Roman records began. Several male Roman praenomina (personal names) derive from the names of these months. For example, Quintus, Sextus, and Decimus correspond to the fifth, sixth, and tenth months—Quintilis, Sextilis, and December.

The masculine praenomina generally ended with -us, while gentilician (family) names ended with -ius, denoting their origin from month names. The pattern focuses on the months of March and May to December, reflecting the original ten-month calendar. For example, Martius (March) and names like Maius (May) influenced various Roman names. January and February were excluded since they were later additions and thus traditionally not part of the naming system.

Contrary to popular belief, the use of Roman number-based names is not simply systematic ordinal birth naming (first, second, etc.). Few early Roman male praenomina correspond to numbers one through four. In fact, names like Primo or Secundus only appear later and primarily outside Rome, especially in Celtic provinces, hinting at non-Roman influences.

Names such as Tertius and Quartus are rare or absent as praenomina but do appear as cognomina (nicknames or family distinctions) or in female names. Women’s names demonstrate a broader use of number-based naming, including names like Tertia (third daughter), possibly reflecting birth order more directly than male names. Still, this is uncertain due to limited evidence.

Some names do not fit neatly into this pattern. For example, Octavianus appears late and is derived from the family name Octavius. Unlike what might be expected if it followed the month-based system, Octavus does not exist as a praenomen. The origin of Aprilis (April) is unclear and likely not from Latin roots. Consequently, no known Roman names derive directly from April. Early Roman authors noted the obscurity surrounding April’s origin and naming.

Following the ancient pattern, Quintilis and Sextilis—months on which names like Quintus and Sextus are based—were renamed July and August in honor of Julius Caesar and Augustus in the 1st century BCE. This occurred centuries after the number-month names originated, so no Roman names developed based on the new month names July and August. Instead, months were renamed after distinguished individuals, reversing the usual naming order.

Other number-based names arose in various contexts. Some gentilician family names, like Petronius and Pomponius, originate from local Oscan languages, related to the numbers four and five. The widespread Roman naming conventions primarily reflect tradition rather than a strict count of birth order or purely numeric lineage.

Roman naming practices were much more tied to tradition and older calendar systems than numerical ordering of children by birth. The numeric-sounding names commonly known, such as Quintus and Sextus, were remnants of an ancient calendar pointing to months instead of to the exact position of a child in a family.

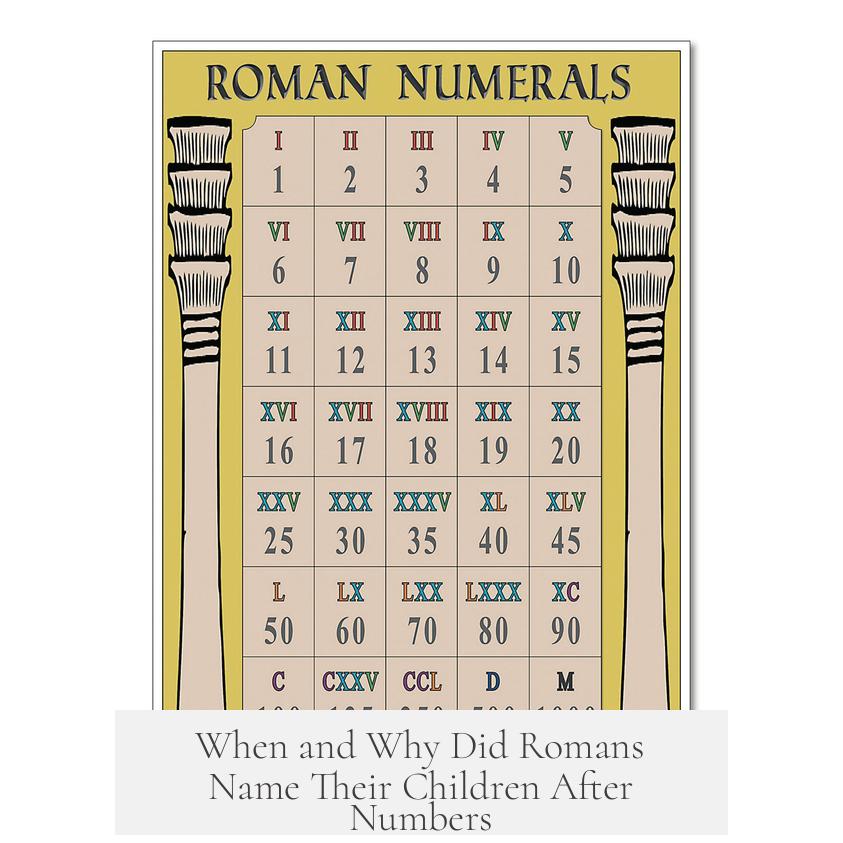

| Name | Meaning / Origin | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Quintus | Fifth month (Quintilis) | Common male praenomen |

| Sextus | Sixth month (Sextilis) | Common male praenomen |

| Decimus | Tenth month (December) | Common male praenomen |

| Tertius / Tertia | Third, often female or used as cognomen | Rare as praenomen |

| Septimus | Seventh | Rare male praenomen |

| Octavianus | Derived from family name Octavius (Eight) | Late male praenomen |

Varro, a 1st-century BCE scholar, proposed that these number-based names derive from months, an idea corroborated by modern scholars. Hans Petersen’s study in 1962 remains an important reference for understanding Roman numeral praenomina. The practice dates back to ancient times, well before January and February were added to the calendar. However, its cultural relevance faded long before the Imperial era.

- Roman number-names mostly come from ancient month names, not birth order.

- Male praenomina like Quintus and Sextus reflect months from March to December.

- January and February are missing from the system due to late calendar additions.

- Female names show more number-based naming linked possibly to birth order (e.g., Tertia).

- Later Roman names and those in provinces sometimes reflect different or non-Roman practices.

- Months July and August were renamed after individuals, not the basis of birth names.

- Many gaps and exceptions remain unexplained due to scarce ancient evidence.

When and Why Did Romans Name Their Children After Numbers?

Romans started naming some of their children after numbers very early, linking those names primarily to the months of the ancient Roman calendar rather than simply birth order. This tradition is more complex and less systematic than popular belief suggests.

Most people guess that names like Quintus or Sextus literally mean “fifth” or “sixth” child. While that’s somewhat true, the reality digs deeper into Roman timekeeping and calendar history. And if you think “numbers as names” was neat, orderly, and consistent, buckle up—it’s a tangled puzzle that even scholars scratch their heads over.

Let’s unpack the story behind these number-names and discover where they come from.

The Ancient Roman Calendar and Naming Origins

A key to understanding Roman number-names lies in the early Roman calendar, which originally had only ten months. This calendar started in March and ended in December. The months’ names reflected their positions: March was the first, Quintilis the fifth, Sextilis the sixth, and so on.

This is why names like Quintus (meaning “fifth”) and Sextus (“sixth”) align with the months Quintilis and Sextilis. Meanwhile, Decimus (“tenth”) corresponds to December, the tenth month in that calendar.

“It’s been suspected since antiquity that January and February were added after this ten-month system, which explains why those months don’t inspire any number-based Roman names.”

So, rather than naming children strictly by birth order, the Romans often named children after the month they were born in. And these names mostly belong to men, following a clear calendar-rooted pattern.

Mens’ Praenomina vs. Women’s Naming Patterns

Interestingly, this naming based on numerals appears mostly in men’s praenomina — the Roman equivalent to first names. Their names often ended with -us (think Quintus, Sextus, Decimus). But women’s names showed a broader range of number-names, like Tertia (third). Could women have been named by birth order more often? The evidence is sparse, but it’s an intriguing idea.

So, for men, the trend was tightly tied to months—mainly March to December—while women’s names hint at more direct numerical birth reference.

Mysteries and Exceptions in Number-Naming

One big surprise: some obvious number-names like Octavus (from “octo” meaning eight) or Nonus (nine) simply do not appear as praenomina. Though related forms, like Octavianus, a family name, pop up later, they’re exceptions rather than the rule.

Even rare names like Septimus (seventh) exist but are considered archaic.

Also puzzling is the month of April. Unlike months named clearly for their numbers (September, October, November, December), April’s name origin is unclear—possibly Etruscan or another lost source. Because April’s name’s meaning is mysterious, the Romans lack number-based names tied to it.

For example, Tertius is not a praenomen but a cognomen (a kind of official nickname). This usage suggests the Romans didn’t rigidly apply number-names as first names beyond certain traditional ones.

Historical Context and Trends

These naming practices very likely date back to the regal period of Rome, centuries before the rise of the Republic, placing them deep in Rome’s prehistoric phase. The pattern faded over centuries as the calendar evolved (remember January and February were late additions). By the Imperial period, the explicit connection between names and birth months had mostly vanished.

A famous Roman scholar, Varro, proposed in the 1st century BCE that the number-name origins are actually month-related, not just ordinal birth numbers. Modern scholarship agrees, especially after Hans Petersen’s detailed 1962 study, which remains the authoritative source today.

Outside Rome: Celtic and Oscan Number-Names

Not all number-names fit neatly into this “month-based” origin.

In Celtic areas within the Roman provinces, we find names like Tertius and Quartus more commonly. This suggests some cultural borrowing or parallel naming customs that used birth order more literally.

Also, family names like Petronius and Pomponius trace back to Oscan numbers for “four” and “five,” showing other numerical roots in nearby Italic languages.

Why Did the Romans Care Enough to Use Numbers for Names?

Using numbers for names offered a practical advantage in early Rome. When literacy was limited and population mobility low, knowing a person’s birth month or order quickly gave useful family information. For aristocrats and politicians, these names also linked them symbolically to time and tradition.

However, this system never became a rigid “rule” for everyday naming. Only a handful of numbers appeared regularly for men, tied to months. Women’s naming practices and provincial customs varied more freely. And as time passed, these conventions gave way to new fashions, honors, and family names.

What Can Modern Readers Take Away from This?

If you’re fascinated by Roman history or thinking about baby names (maybe “Quintus” is due for a comeback?), remember the rich context behind these labels. Naming was about more than birth order. It anchored families to ancient calendars and cultural heritage.

- Think of “Quintus” and “Sextus” as living relics from a time when months and names danced closely together—

- while striking oddities like the missing Octavus remind us that ancient traditions were more flexible than they seem.

- Women’s names hint at a hidden system we might discover more about.

Finally, this naming pattern reflects a Rome both pragmatic and poetic: practical enough to track birth months but imbued with symbolic lines to their ancestors’ mysterious, ten-month world.

Summary Table of Key Number-Names and Their Meanings

| Roman Name | Meaning | Type | Frequency and Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quintus | Fifth (month of Quintilis) | Male Praenomen | Common |

| Sextus | Sixth (month of Sextilis) | Male Praenomen | Common |

| Decimus | Tenth (December) | Male Praenomen | Common |

| Septimus | Seventh | Male Praenomen | Rare, Archaic |

| Tertius / Tertia | Third | Cognomen / Female Praenomen | Rare as male first name; Female name exists |

| Octavianus | Derived from Octavius (family name) | Cognomen/Gentilician | Late, modeled on family name |

| Quartus | Fourth | Rare male name, mainly Celtic origins | Sporadic |

| Nonus | Ninth | Not documented as praenomen | Unknown |

In Conclusion

Romans named some children after numbers, mostly connected to months—especially when the calendar only had ten months. This tradition is ancient, practical, and symbolic but not as neat as popular tales suggest.

While men’s names like Quintus, Sextus, and Decimus dominate, women and provincial cultures added richness and variation. Missing number-names remind us of history’s gaps and the mysteries locked in ancient calendars.

Next time you hear a Roman name, remember it might mark a birth month, team tradition, or a mystery from centuries past. Now you know when and why the Romans sometimes named their children after numbers—and it’s more fascinating than simple counting!