People began having surnames at different times and places depending on the type of name in use. The earliest forms were bynames or epithets, which were descriptive and not hereditary. Fixed, hereditary surnames as we know them appeared mainly in England, France, Ireland, and Scotland from the 1100s onward. Patronymics, last names derived from a father’s first name, were used earlier and in some regions remain in use even today.

The first type of last names were bynames, also known as epithets. These described a person’s occupation, appearance, or origin. Examples include famous historical figures like Alexander the Great and Richard the Lionheart. By the Norman Invasion of England in 1066, both nobility and commoners used bynames—names such as John the Smith or William of Oxford are recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. However, bynames usually did not pass down through generations; they identified a person during their lifetime but rarely their descendants.

The second type is the patronymic system, where the last name derives from one’s father’s given name. This practice appeared in various cultures with varying forms. For example:

- Scottish names often use the prefix “Mc” or “Mac,” meaning “son of,” as in McDonald from Donald

- Dutch versions commonly end with “-sen,” like Donaldsen

- Russian names frequently use suffixes like “-ovich,” as in Donaldovich

Patronymic names change with each generation. If John Donaldsen has a son named Peter, Peter’s last name would be Johnsen, not Donaldsen. In some cultures, a second identifier called a cognomen acted like a middle name to differentiate individuals with the same patronymic.

A third, older type came from ancient Rome. Roman names included a clan name or nomen, representing a distant ancestor shared by many. This naming dated back to roughly 700 BC and continued until around 600 AD. Roman clan names were hereditary but based more on extended family groups than direct parentage.

True hereditary fixed surnames like modern last names emerged mainly in England, Scotland, Ireland, and parts of France around the 1100s after the Norman Conquest. The Normans initially continued the practice of bynames but passed them down to their children. Over the next two centuries, this practice expanded and became mandatory, replacing the earlier, more fluid byname and patronymic systems.

Fixed surnames simplified identification for legal, tax, and property matters. By the late 1200s, hereditary surnames were common among the English and neighboring populations. For example, the surname Chaucer was recorded from the late 1200s onward and passed down through Geoffrey Chaucer and his descendants. Early surnames often included small words like “de,” “of,” or “the” to indicate origin or occupation. These prepositions dropped out around the 1300s, streamlining surnames to forms like “John Smith” instead of “John the Smith.”

The timeline of surname adoption varies greatly by region and type:

- Bynames arose by the start of the Middle Ages and were in widespread use among peasants throughout Europe.

- Patronymics appeared as early as the 600s or 700s, with some regions using them extensively until recent centuries. For instance, Italian patronymics faded by the 1500s, while Sweden used them well into the 20th century.

- Fixed surnames began around the 1100s in England, France, and Ireland, expanding over 800 years across most European countries. Today, Iceland remains one of the few places that predominantly uses patronymics instead of fixed surnames.

Before fixed surnames became established, people used various other identifiers in speech and writing to distinguish individuals. Common examples include:

- Localizers: “John from Newcastle”

- Physical traits or nicknames: “Big John” or “Red-haired John”

- Patronymics: “David’s John” (son of David)

| Type of Name | Origin | Inheritance | Example | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bynames (Epithets) | Descriptive (occupation, appearance) | Usually single generation | John the Smith, Richard the Lionheart | Early Middle Ages onward |

| Patronymics | Father’s given name | Changes each generation | McDonald, Donaldsen, Donaldovich | 600s-1000s onward (varies by region) |

| Roman Clan Names | Distant ancestor clan | Hereditary by clan | Gaius Julius Caesar | 700 BC to 600 AD |

| Fixed Surnames | Various origins | Hereditary and stable | Chaucer, Smith | 1100s onward in Europe |

In summary, surnames started as descriptive or patronymic identifiers before evolving into the stable, hereditary forms common today. Their origins trace to different parts of Europe and different times:

- Bynames appeared in the early Middle Ages and were widespread by the 11th century.

- Patronymics began in the early medieval period, lasting in some cultures until modern times.

- Fixed surnames emerged primarily after the Norman Conquest around the 1100s in the British Isles and spread gradually through Europe over centuries.

- Additional identifiers like place names and physical traits complemented surnames to avoid confusion in communities.

When and Where Did People Start Having Surnames?

People started having surnames, or fixed family names passed from generation to generation, around the 1100s in England, France, Ireland, and Scotland. This practice then spread gradually across Europe over the next several centuries.

In a nutshell, surnames as we know them — those family names that stick through generations — were not always a thing. Before surnames became fixed, people used different name systems that evolved over time. Let’s unravel this fascinating journey together.

The Early Days: Bynames and Epithets

Way back before fixed surnames, people relied mainly on bynames, also called epithets. These were descriptive tags attached to a person’s first name — think of Alexander the Great or Richard the Lionheart. They told you something about the person, like their personality, occupation, or where they were from.

Unlike modern surnames, bynames weren’t often passed down to children. If you were dubbed “John the Smith,” your son wouldn’t necessarily be “Smith.” But once you had that byname, you generally kept it for life unless you moved away or became famous (which for peasants was pretty rare).

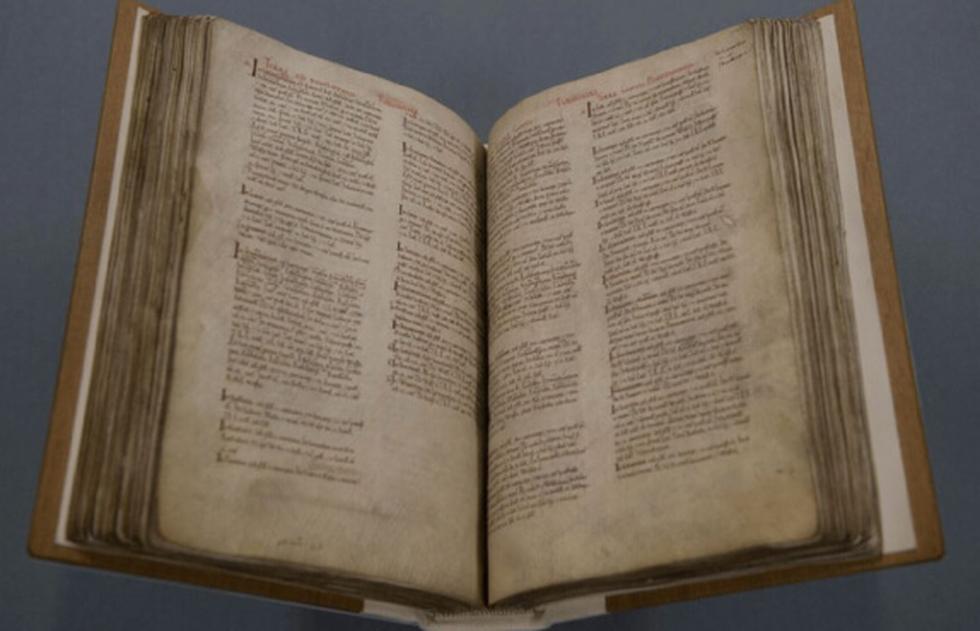

Even peasants picked up these descriptive bynames by the start of the Middle Ages. A peek into England’s Domesday Book, compiled in 1079, reveals plenty of examples: “John the Smith,” “William of Oxford,” or “Richard, son of Peter.” So bynames were the practical tags people used to deal with the growing population and comfuse-less communication.

Patronymics: The Father’s Name as a Family Marker

Around the 600s or 700s, in some European regions, a new system gained popularity: patronymics. Here, the last name was derived from your father’s first name. If your dad was Donald, you became McDonald in Scotland, Donaldsen in the Netherlands, or Donaldovich in Russia.

The twist? The patronymic changed with every generation. Your son would take your first name as his last name. This meant last names weren’t fixed family markers but rather shifting identifiers across generations.

Some cultures added a cognomen, a second last name resembling a byname, for clarifying individuals with the same patronymic. It somewhat worked like a middle name, helping distinguish between “John Donaldsen” and “John Donaldsen”—they still needed help keeping track!

This practice still echoes today—names like Johnson (son of John) or Ivanovich (son of Ivan) show patronymic roots. Sweden kept this system until after 1900, while Iceland continues it to this day, proving some traditions never truly die.

Roman Names: The Ancient Clan Connection

The Romans had their twist on last names. Instead of a father’s name, they used clan names that traced back to distant ancestors. These clan names identified broader family groups within Roman society.

Roman naming conventions go way back, starting near 700 BC and lasting until around the 600s AD. Unlike patronymics, this was a more fixed surname system, but it was tied to clans instead of immediate ancestors. Think of it as ancient branding for extended family loyalty within Rome’s vast population.

The Arrival of Fixed Surnames: The Breakthrough in the 1100s

Now, here comes the big milestone: fixed surnames as we know them emerged around the 1100s. This happened primarily in England, France, Ireland, and Scotland, driven largely by Norman influence.

The Normans, who invaded England in 1066, originally used bynames that identified individuals by characteristics or origin. Unlike earlier bynames, however, these began to stick within noble families. Sons kept the same last names as their fathers, which then passed to their sons, and so on.

By the 1200s, fixed surnames became widespread. One excellent example is the Chaucer family. Robert Chaucer lived in the late 1200s. His grandson, Geoffrey Chaucer, born in 1343, became famous for writing The Canterbury Tales. Geoffrey’s son Thomas kept the surname Chaucer too. There you go — a surname firmly rooted across generations by the 14th century.

Interestingly, many surnames back then still included articles like ‘de’, ‘the’, or ‘of’ — for example, ‘Paon de Roet’ (Paon the Red). But by the 1300s and during the Hundred Years’ War, these articles fell out of favor. Hence, “John Smith” replaced “John the Smith,” simplifying names.

Why Did Fixed Surnames Catch On?

We don’t have a crystal-clear historical explanation, but fixed surnames likely made life easier for lords and governments. Keeping track of taxes, land ownership, and debts became less tangled when people had permanent last names. Imagine the chaos trying to tax “John the Smith” one year and “John the Baker” next when it referred to the same guy. Fixed surnames brought clarity and legal consistency.

The Spread of Surnames Across Europe and Beyond

From their roots in England, France, Ireland, and Scotland, fixed surnames spread slowly through Europe over the next 800 years or so. By the time we hit modern history, most European countries had embraced the system.

Exceptions remained though. Sweden clung to patronymics longer, and Iceland still uses that system distinctive to this day. Different naming customs endure globally, but the fixed surname system largely dominates Western identity.

Bible Names: The Early Consistency of Identifiers?

You might wonder about Biblical names and if surnames appeared there. Ancient biblical names like Judas Iscariot and Mary Magdalene give us clues. In their cases, their ‘last names’ function more like bynames or geographical descriptors.

For example, Iscariot in Judas Iscariot might mean ‘man of Kerioth’—a place—or could be a tag meaning ‘liar’ or ‘false one,’ clearly a descriptive epithet rather than a family name. Mary Magdalene’s name means she came from Magdala, so it’s a byname pointing to her hometown.

So, even biblical names used practical markers to clarify identity, not fixed hereditary surnames.

More Than Last Names: Other Ways People Identified Themselves

Before and even alongside surnames, people often relied on other identifier types.

- Patronymics: The father’s name as we saw earlier.

- Localisers: Names indicating where a person was from, like “John of Newcastle.”

- Distinguishers: Nicknames based on traits, like “Big John” or “Red-haired John.”

Imagine a village full of Johns! Without surnames, people had to get creative to keep conversations clear. Even today, some of these survive as nicknames or descriptors.

So What’s the Big Deal About Knowing When Surnames Started?

Understanding when and where people started having surnames puts a spotlight on how societies grew more complex. As populations expanded, simple first names no longer sufficed to identify everyone properly. We needed more accurate ways to distinguish individuals, ensure accurate legal documentation, and maintain social order — surnames met this need perfectly.

Knowing this history also reveals the fluidity of identity and how cultures married convenience with tradition. From wandering descriptive nicknames to tightly held family names, surnames tell stories about migration, occupation, social rank, and geography.

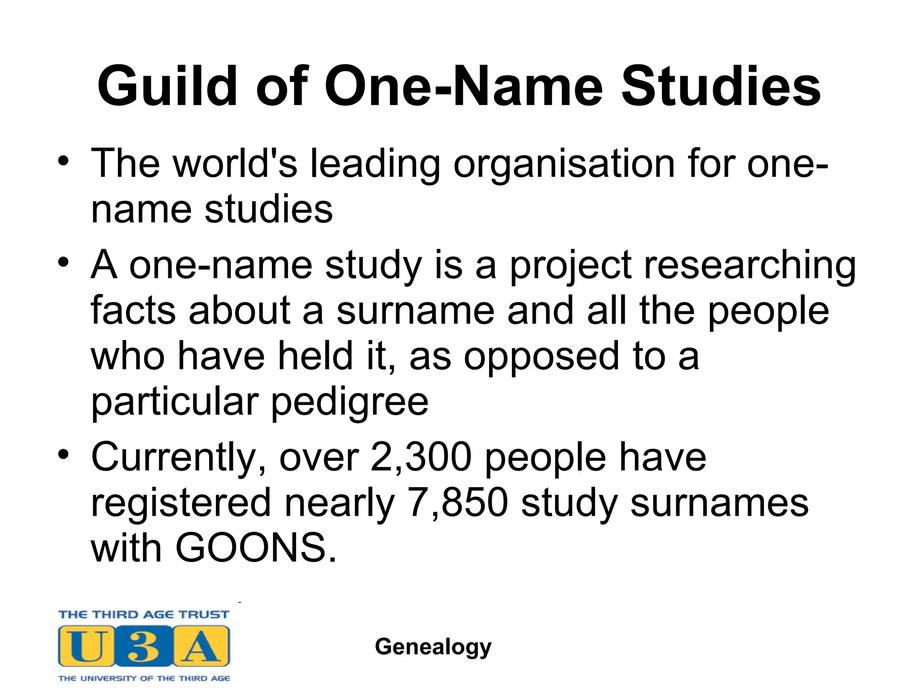

Want to Dig Deeper Into Your Own Surname?

Ever tried tracing the story behind your last name? It can be quite revealing. Did your ancestors adopt a fixed surname early, or were they part of a patronymic system? What might their bynames or localisers have been? Now you know surnames mainly took root from the 1100s in Western Europe, so those rich stories often start around then.

Next time you hear a name like “Smith,” “Johnson,” or “de Roet,” think back to the medieval world where lords, peasants, and adventurous Normans alike began crafting these name traditions. It’s history living in your own name!

Final Thoughts

Surnames, as we use them, began in the 1100s in Western Europe but evolved from earlier nametag systems like bynames and patronymics. From useful descriptors that faded with the individual’s life to fixed names that shaped family legacies, surnames reflect much more than simple identity—they chart human social progress.

So next time someone asks when and where did people start having surnames? you now have the medieval timeline, rich examples, and clear reasons at your fingertips. And maybe you’ll smile thinking about John the Smith becoming John Smith, the forefather of family history and tax records alike.