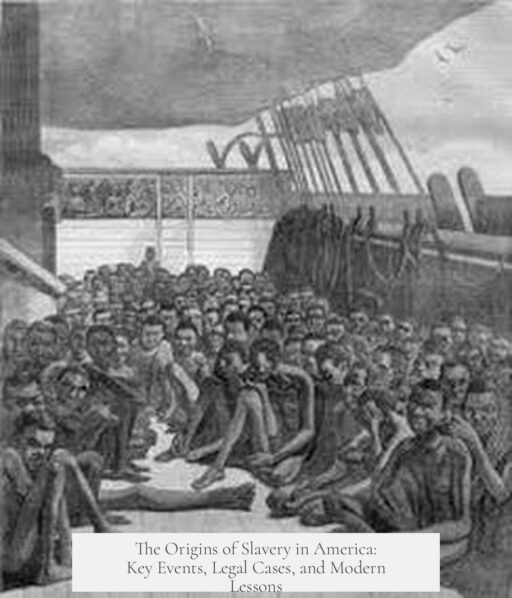

Slavery in America originates in 1619, when the first African slaves arrive in Jamestown, Virginia. Initially, these Africans were treated similarly to white indentured servants, bound to work for a fixed period, usually seven years, after which they gained freedom. This early system did not reflect permanent enslavement but a form of temporary labor. Over the next decades, this model shifted drastically toward racialized, lifelong slavery.

Early 17th-century Virginia primarily relied on indentured servitude. Poor Europeans came under contracts granting freedom after service, typically related to land or economic opportunity. Africans brought during this period were often under similar contracts, sharing comparable legal and social standings with European servants. Tobacco plantations fueled Virginia’s economy, and both groups worked in agriculture.

By mid-century, the transition from indentured servants to perpetual slaves laid the foundation of the American slavery system. Laws began to entrench lifelong servitude for Africans. The 1640 case of John Punch is notable; he was an African indentured servant sentenced to servitude for life after attempting to escape, while two European servants who fled with him received only extended terms. This case marks an early legal distinction setting African laborers apart.

Similarly, in 1655, John Casor’s case further codified slavery. After his indenture ended, his master sued to keep him enslaved for life—the court ruled in favor of permanent servitude. These cases illustrate a growing legal framework transforming Africans into de jure property, unlike European indentured servants.

Several factors explain the racialization of slavery. Early colonists divided people based on religion and culture rather than race. Indentured servitude applied to poor Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans alike. However, conflict and power dynamics shaped changes.

The 1676 Bacon’s Rebellion highlights this shift. Nathaniel Bacon, an English settler, led a revolt involving white indentured servants against the colony’s government and Native Americans. Fear among the colonial elite grew over empowered freed servants potentially challenging the social order. African slaves, unfamiliar with local language and geography, were viewed as less likely to rebel, making them preferable laborers. This fueled a transition to racial slavery, where Africans and their descendants were enslaved for life, a status inherited by their children.

By the establishment of the United States, slavery was largely confined to Africans and their descendants. The institution was a life sentence, extending to subsequent generations, shaping profound social and economic structures.

The 18th century brought political tension around slavery. Some legislators pushed to end importation and practice of slavery during the Constitutional Convention and early republic years. The 1807 ban on importing African slaves reflects efforts to curtail the growth of slavery, although it did not immediately end the practice. The abolitionist movement began with escaped slaves and white allies inspired by religious revivalism, gaining traction especially in the North. Conflicts over slavery fueled sectional tensions that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

| Period | Key Developments |

|---|---|

| 1619 | First African slaves arrive in Jamestown; treated as indentured servants |

| 1640 | John Punch case establishes life servitude distinction for Africans |

| 1655 | John Casor declared slave for life, defining racialized slavery |

| 1676 | Bacon’s Rebellion prompts shift toward racial enslavement for control |

| 1807 | Importation of African slaves outlawed; abolition movement gains strength |

The development of slavery in America unfolds in stages. It begins with temporary labor contracts crossing racial lines. External pressures and fears shift this into a rigid, racial system of perpetual enslavement, legal and socially enforced.

- 1619 marks the origin with African slaves brought to Virginia under indenture.

- Mid 17th century laws create life-long slavery, distinguishing Africans legally from Europeans.

- Bacon’s Rebellion intensifies racial distinctions to maintain elite control.

- Legal cases such as John Punch and John Casor are milestones in codifying racial slavery.

- Abolition efforts start in late 18th century but slavery remains entrenched until the Civil War.

When and How Did Slavery Originate in America?

Slavery in America officially begins in 1619, but not quite how many imagine it. The first Africans arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, introduced not as slaves outright but more like indentured servants. These original Africans were contracted laborers expected to work for a set number of years—typically seven—before gaining their freedom.

This story is quite different from the perpetual, hereditary slavery that many associate with American history. So, how did this shift happen? It’s a wild journey from a labor system that resembled European indentured servitude to one built on permanent, racialized enslavement.

From Indentured Servants to Lifelong Slaves

In the early 1600s, the labor market in Virginia was fluid. Not only Africans but poor whites worked as indentured servants. These workers traded a fixed number of years of servitude for eventual freedom and sometimes land. The tobacco economy was booming, and cheap labor was essential.

By the mid-17th century, laws in Virginia created a sharp divide. The system changed drastically when slavery became codified for Africans, ushering in a new era of permanent enslavement. Tobacco plantations now favored slaves over indentured servants because slaves worked for life, creating a cost-effective labor force planted deeply into the colony’s economy.

Interestingly, early African workers in the 1620s were still often on contracts similar to whites’. They weren’t automatically enslaved for life. Their transition into lifelong slavery was gradual, driven by legal and economic pressures.

How Race Became the Defining Factor

Here’s where things get especially tricky and revealing: In the beginning, race didn’t dictate status as strictly as it later did. Colonists viewed people mostly through religious and cultural lenses. Poor Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans could all be indentured servants.

A major turning point involves Nathaniel Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Bacon, a newcomer to Virginia, led a revolt with indentured servants against the governor. This made the ruling class uneasy. Serve people who might rise up posed a big risk.

To prevent future insurrections, the system increasingly divided laborers by race. Africans were seen as less threatening because they often lacked local knowledge and language skills, making them less likely to rebel like the white indentured servants and Native Americans. Thus, slavery morphed into a racial institution. Slavery became a way to ensure a permanent labor force that posed minimal threat.

Key Legal Cases—John Punch and John Casor

Legal records help trace slavery’s hardening in America. John Punch, an African indentured servant, ran away in 1640 alongside two whites. His punishment? He was sentenced to serve for life. The two white escapees received only a few extra years. This landmark case shows the shift toward racialized, lifelong slavery.

Another case, John Casor in 1655, pushed the system further. Casor’s indenture ended, but his master sued to keep him as a slave for life. The courts agreed.

Some historians argue John Punch was the first documented lifelong slave, others credit John Casor. What’s clear is that these cases represent a system evolving from contractual labor into an institution where Africans were property for life.

Attempts to End Slavery—A Rocky Road

Despite the growing institution of slavery, there were persistent efforts to stop it. During the Constitutional Convention and later, some legislators pushed for abolition. In 1807, the importation of new African slaves was banned by law—yet illegal buying and trading still occurred.

The abolitionist movement gained steam, fueled by escaped slaves and sympathizing whites, often inspired by religious awakenings. This created a North-South divide full of legislative compromises, laying groundwork for the Civil War.

What Can We Learn Today?

This complex history reveals slavery’s origins in America as a gradual, evolving system rather than an abrupt institution. Starting as temporary labor, it slowly became an immutable racial caste linked to economic interests and fear of uprisings.

So next time you hear “slavery began in 1619,” remember: the story has layers. It took decades of legal battles, economic shifts, and social fears to transform those first Africans’ lives from indentured servants into lifelong slaves — a transition tied deeply to race and power dynamics that still echo today.

Wondering how history shapes current social issues? Reflect on how economic necessity, fear, race, and law intertwined to form a system that endured centuries. It’s not just the date 1619; it’s the complicated journey from servitude to slavery that defines America’s origins.