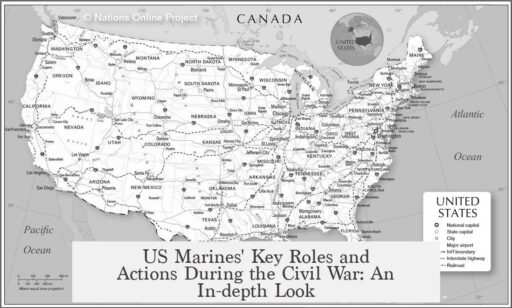

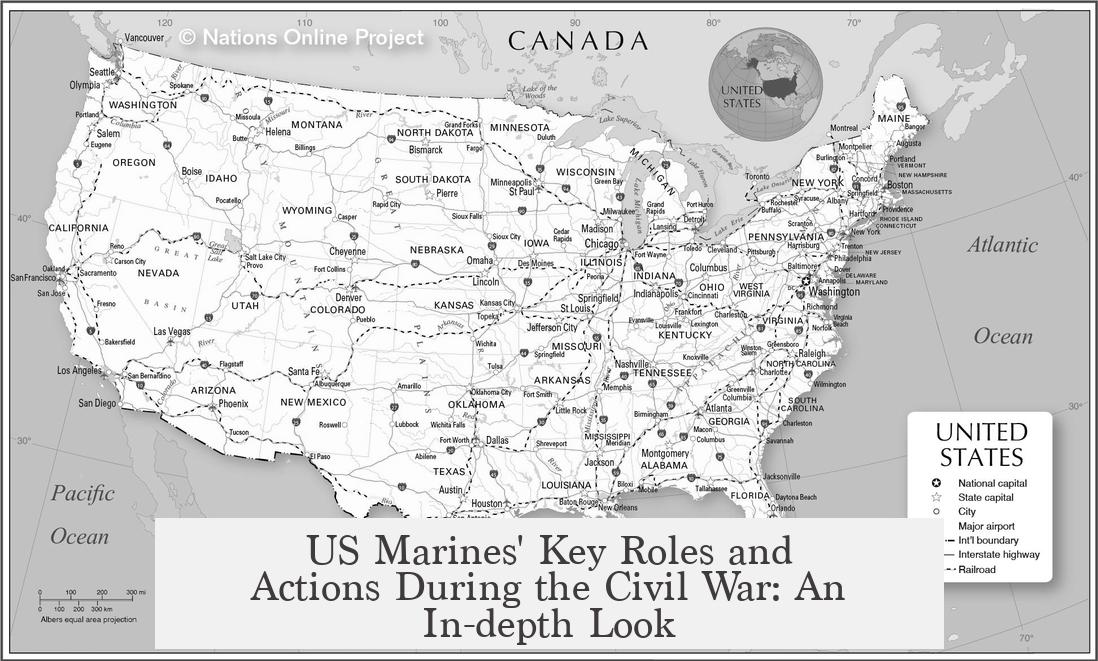

During the American Civil War, the U.S. Marines mainly served aboard naval vessels and at naval installations, with limited involvement in land battles. Their small size and naval focus restricted their roles to shipboard service, boarding parties, shore assaults, and amphibious operations. Although they participated in some key engagements, large-scale land combat was rare.

The Marine Corps began the war very small, with only 1,758 men and 63 officers. It struggled to maintain even that modest size due to officer resignations and lack of enlistment incentives. Many officers left, and enlistments were long-term without bounties, which made recruitment difficult. By the war’s end, the Corps had grown to just 3,882 men, a tiny force compared to the Army.

The Marines’ primary duty was guarding naval yards and serving aboard ships. Most of their combat experience came from naval activities, such as boarding enemy vessels and conducting shore assaults from the sea. Land combat was limited, and the Corps rarely acted independently on terrestrial battlefields.

- Pre-war action: Marines played a role in suppressing John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859. A detachment of 87 Marines arrived with artillery to help militia and soldiers. They led an assault on the arsenal, suffering casualties during the fight.

- First major battle: At the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run), about 350 Marines from the Navy Yard garrison marched alongside the Army. Most were new recruits with little training. They showed bravery but did not excel in combat. During the chaotic Union retreat, many fled, and some were arrested by provost marshals. The battalion suffered eight killed, sixteen wounded, and sixteen missing.

Following Manassas, Marines returned mainly to ship and shore roles. One of their significant naval missions involved the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, designed to disrupt Confederate supply lines around Charleston and Savannah. Approximately 157 Marines and 350 sailors participated in riverine attacks on railroads supporting Confederate logistics. However, the operation had limited success and ended after Sherman’s capture of Savannah.

Some of the Marines’ most notable naval actions occurred aboard warships. In September 1861, Marines on the USS Colorado boarded and destroyed the Confederate privateer Judah under cover of night, also disabling shore artillery. At the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff in May 1862, Marines manned the USS Galena’s guns after the naval gun crew was incapacitated. Corporal Mackie earned the first Marine Medal of Honor for his leadership during this fight.

The Marines also took part in amphibious assaults. The largest was the January 1865 attack on Fort Fisher, a Confederate coastal stronghold guarding Wilmington, North Carolina. Four hundred Marines and 1,600 sailors landed to assault from the sea alongside 180 Army Marines attacking by land. Despite opening a breach in the fort’s walls, the naval landing stalled due to Army delays, forcing Marines and sailors to hold their position and act as a diversion. The Army’s land assault eventually secured the fort, ending major Marine combat operations in the war.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Strength at War Start | 1,758 men, 63 officers |

| Strength at War End | 3,882 men |

| Primary Roles | Naval installation security, shipboard service, boarding parties |

| Major Land Engagements | John Brown’s Raid, First Battle of Manassas, limited shore assaults |

| Notable Naval Actions | Judah raid, Battle of Drewry’s Bluff |

| Largest Amphibious Assault | Fort Fisher (January 1865) |

Overall, the Marines contributed to the Union war effort mostly through naval engagements and specialized amphibious operations. Their small size and emphasis on shipboard duties limited their independent land combat role after the initial battle of Bull Run. The Corps helped suppress insurrections and supported blockades but remained a modest force within the larger military framework.

Key takeaways:

- The U.S. Marines stayed small and mostly served at sea and naval bases during the Civil War.

- They fought in few land battles, notably John Brown’s raid and First Bull Run, but had limited success on land afterward.

- Significant naval actions included raids on Confederate ships and artillery, such as at Drewry’s Bluff.

- The Marines participated in amphibious assaults, with Fort Fisher being the largest and last major one.

- Challenges included officer resignations, recruitment limits, and their naval service focus.

What Were the US Marines Doing During the Civil War? The Untold Naval Infantry Story

During the American Civil War, the US Marines played a small but unique role, primarily serving aboard naval vessels and at naval installations, with occasional amphibious assaults and limited land battles. They were not the large ground force we often imagine but a naval infantry force operating in specialized roles. Let’s dive into what those roles were, their struggles, and their notable actions during this turbulent time.

First, it’s important to realize that the Marine Corps was tiny in size. At the war’s outbreak, they numbered just 1,758 men and 63 officers. Compared to the massive Union and Confederate armies, that’s… well, it’s a lot smaller than you might expect.

The Corps had a tough time keeping its ranks full. Even though enlisted Marines rarely deserted, 20 officers resigned early on. Unlike the Army, there were no enlistment bounties or short-term contracts to attract recruits. They stuck with small numbers, and even by war’s end, the Corps only grew to 3,882 men. That’s it. Tiny but determined.

Naval Roles: The Marines at Sea and Shore

The Marines primarily operated from ships or naval bases. Their core missions involved guarding navy yards, manning shipboard guns, and participating in boarding parties and shore assaults. Unlike with the Army, there wasn’t a big ground war front where Marines stormed trenches for months on end. Their fight was more targeted and naval-oriented.

So what did that look like in practice? Take the early raid on the steamship Judah in September 1861. Marines from the USS Colorado and some sailors slipped out under cover of darkness, boarded the enemy vessel, set it afire, and even destroyed a shore gun defending the naval yard. A classic hit-and-run tactic—more pirate-y than trench warfare.

Early Land Engagements: Not Exactly Chesty Puller, But Not Chicken Either

Before the war, the Marines had already flexed some muscle suppressing John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry in 1859. A force of 87 Marines, supported by two 12-pounder cannons, stormed the arsenal building held by Brown’s insurgents. They lost one Marine in the assault, showing early on that Marines put skin in the game beyond the sea.

Then, the First Battle of Manassas (or Bull Run), the first major land fight of the Civil War, saw around 350 Marines marched into Virginia alongside the Army as a garrison force. Most were new recruits, barely trained, yet they tried to hold the line. The results were mixed. Some acted as a rear guard during the chaotic Union retreat, but many fled, and around 70 were arrested by the Army’s provost guards. The casualty count was modest: 8 killed, 16 missing, and 16 wounded.

This limited and somewhat rocky ground engagement explains why, after Manassas, the Marines mostly stuck to naval roles—their strength was aboard ships, not sprawling land battles.

South Atlantic Blockading Squadron: River Raids and Rough Waters

In one notable operation, about 157 Marines and 350 sailors formed part of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. They ventured into riverine attacks aimed at disrupting the Charleston and Savannah railroads, supporting Sherman’s penetrating campaign. They mixed with Army units for about a month but largely failed to achieve major success. After General Sherman captured Savannah, the operation wound down.

Heroics Afloat: The Battle at Drewry’s Bluff

On May 15, 1862, Marines aboard the USS Galena stepped into the breach—literally. Under severe enemy fire, when the ship’s guncrew fell, Marine Corporal Mackie took over the Parrott rifle and helped fend off Confederate shore defenses. This earned him the first-ever Marine Medal of Honor. Yes, even with limited numbers and mostly naval duties, the Marines proved lethal and capable of extreme valor.

The Amphibious Assault on Fort Fisher

The largest Marine amphibious operation of the war occurred on January 15, 1865. About 400 Marines and 1,600 sailors landed to assault Fort Fisher, a Confederate stronghold guarding Wilmington, North Carolina. The Army attacked from land with an additional 180 Marines. However, the naval landing stalled due to delays on the Army’s side. Marines and sailors held their ground and served as a diversion, allowing the land assault to eventually succeed. This combined sea-land effort underlines the Marines’ unique expertise in amphibious warfare, a domain other ground forces lacked.

Why Didn’t US Marines Fight More on Land?

The answer lies in numbers, training, and mission focus. Compared to the tens of thousands in the Army, the Marine Corps was a speck on the map. Most Marines were trained for naval duties and not extended land campaigns. The Corps functioned mainly as naval infantry, and their value was in shipboard combat, boarding actions, and targeted amphibious operations.

Given these facts, it is clear that the Marines during the Civil War were a specialized force. They weren’t the bulky foot soldiers storming enemy trenches by the thousands. They were the sharp naval infantry, stormtroopers of the sea if you will—operating on rivers, forts, and ships, swinging the fight in critical moments with precision strikes and steadfast shipboard defense.

Wrapping Up

The US Marines in the Civil War were a small force with a big impact in naval and amphibious theaters. Their engagements ranged from suppressing pre-war insurrections, fighting alongside Army units at Bull Run, daring river raids, dramatic shipboard battles, to amphibious attacks like Fort Fisher’s seizure. Though outnumbered and limited by their naval-centric role, their legacy of courage and versatility remains vital to understanding Civil War combat dynamics.

So next time you picture Civil War combat, remember the Marines: the handful of sailors in blue who boarded enemy ships in the dead of night, manned guns under fire on the Galena, and stormed Fort Fisher’s defenses on the shore. They might not have been the headline act on the battlefield, but their role was crucial in carving Union naval supremacy.

Sources

Mostly sourced from American Civil War Marines 1861-65 by Ron Field