The Anglo-Saxons before the spread of Christianity held a complex, varied spiritual belief system rooted in paganism, focused on local deities, natural features, and a spirited world rather than a fixed pantheon. Their beliefs were intertwined with their social structure and warrior culture, involving ritual sacrifices, totemic animals, and reverence for sacred landscapes.

Before Christianity gained prominence in England, the spiritual life of the Anglo-Saxons was characterized by localized pagan practices and worldviews. These beliefs are difficult to reconstruct fully due to scarce sources and biased Christian records, which often only mention paganism in critical terms or fragmentary descriptions. Scholars agree that Anglo-Saxon paganism was not uniform but varied by region, tribe, and circumstance.

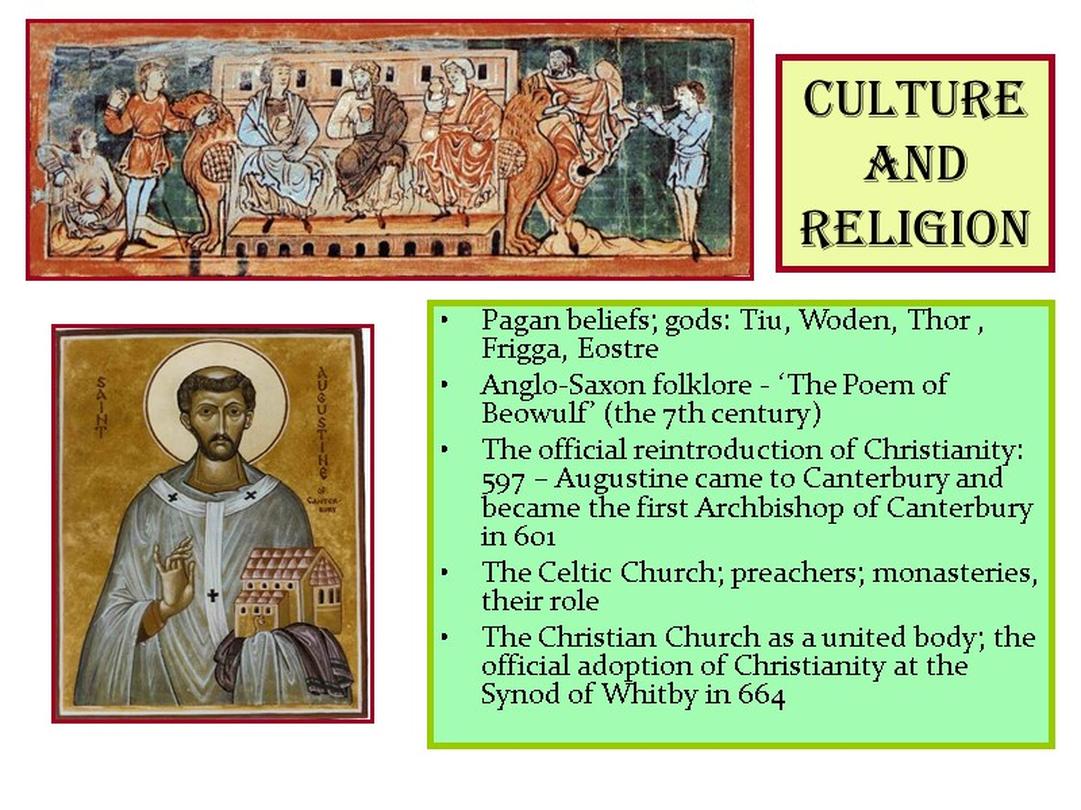

Christianization did not completely replace earlier beliefs but gradually integrated with them. For example, early Christian missions such as Augustine of Canterbury’s arrival in 595-7 faced established Celtic Christian communities and lingering pagan practices, indicating that Christianity already existed in Britain alongside native beliefs. Thus, Anglo-Saxon paganism was resilient, especially among the ruling classes, where religion was closely tied to political authority and social order.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Nature of Beliefs | Non-centralized, diverse practices; more focused on spirits and sacred places than a formal pantheon |

| Totemic Elements | Worship or reverence of animals like horses, wolves, ravens, boars, and bears |

| Spirits and Supernatural Beings | Belief in beings located in natural landscapes such as bogs or burial mounds (e.g., “Grendel” type figures) |

| Rituals and Practices | Cremation burials, boat burials, animal sacrifices, lavish grave goods |

| Religious Authority | Priesthood of tribal or aristocratic priests, but no centralized religious system like Christianity’s |

The spiritual system emphasized a close relationship with the natural world. Sacred natural features — streams, wells, bogs, and ancient burial mounds — played a vital role in religious observance. These places might also connect with legendary beings called Jotun or giants. Pagan burial sites and artifacts such as those found at Sutton Hoo reveal a mix of symbolic weaponry and sometimes Christian-influenced items, reflecting this cultural fusion during conversion.

Animal symbolism was prominent. Horses were especially significant, mirroring continental Saxon beliefs. Other animals like bears, boars, ravens, and falcons appeared in myth and ritual. These animals may have symbolized tribal identities or protective spirits. The spiritual world contained more than gods; it also included spirits or monsters known from folklore and epic tradition. These creatures were not gods but occupied the natural and mystical environment in a way that shaped the Anglo-Saxon worldview.

The religious leaders were most likely tribal priests or aristocrats exercising both spiritual and political power. This connection linked royal authority to divine sanction. Unlike Christianity’s hierarchical church organization, Anglo-Saxon paganism allowed pluralistic beliefs and practices. This flexibility aided the gradual integration of Christianity over time, as local traditions adapted to new religious ideas.

Christian writers like Bede often criticized pagan practices, highlighting aspects such as idol worship and divination. However, in literary works like The Dream of the Rood, pre-Christian heroic values blend with Christian theology. This poem portrays Christ as a heroic warrior lord, a figure understandable to Anglo-Saxon audiences familiar with warrior culture. It symbolizes the cultural negotiation between old beliefs and new Christian faith.

- Anglo-Saxon paganism was diverse and localized rather than centralized or uniform.

- Beliefs involved spirits, sacred natural sites, and totemic animals rather than a fixed pantheon.

- Material culture, such as boat burials and animal sacrifices, illustrates persistent pagan ritual practices.

- Priests held important political and religious roles but lacked a centralized authority.

- Christianity gradually merged with pagan traditions rather than fully replacing them immediately.

What Were the Spiritual Beliefs of the Anglo-Saxons Before the Spread of Christianity?

Simply put, the Anglo-Saxons before widespread Christianity practiced a form of Germanic paganism that was rich, varied, and deeply integrated into their daily lives and social structure. They revered natural features, performed ritual sacrifices, and believed in a spirited world filled with supernatural beings—none of which comfortably fit into a neat, formalized religion like Christianity. But to truly understand their spiritual beliefs, we need to dive deeper into the tangled tapestry of their culture, myth, and artifacts.

Think of Anglo-Saxon spiritual beliefs as an old, sprawling forest—dense, intricate, with many paths leading in different directions. There’s no single “pantheon” roadmap, no universal creed. Instead, it’s a mosaic, sometimes contradictory, often blended with hints of early Christian thought that had already trickled in before the official mission of Augustine of Canterbury landed in 597 AD.

Christian Roots Before Augustine: A Surprising Starter

Contrary to popular shortcuts in textbooks, Christianity hadn’t dropped straight from the sky with Augustine. The reality is more interesting. Britain and its people were already partly Christianized before Augustine showed up. Kings had married Christian princesses, and Celtic Christian communities were well established. Augustine was less a miraculous bringer of Christianity, more an agent extending Roman Catholic influence, negotiating his way with existing Christian authorities.

This early Christian presence adds an important backdrop—Anglo-Saxon paganism didn’t vanish overnight but coexisted and eventually intertwined with Christian ideas. Augustine had some political battles with Celtic bishops who had different beliefs and practices, showing how spiritual beliefs were diverse and contested already.

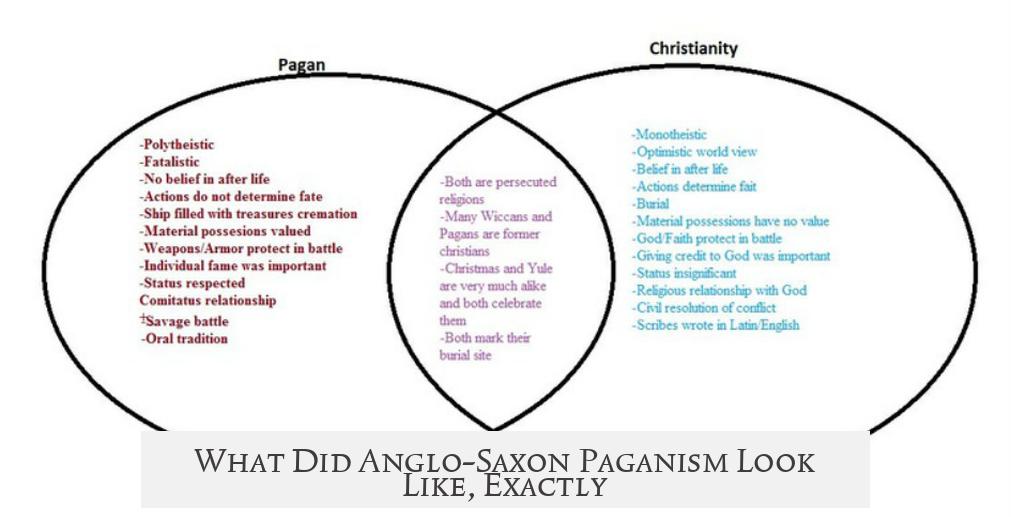

What Did Anglo-Saxon Paganism Look Like, Exactly?

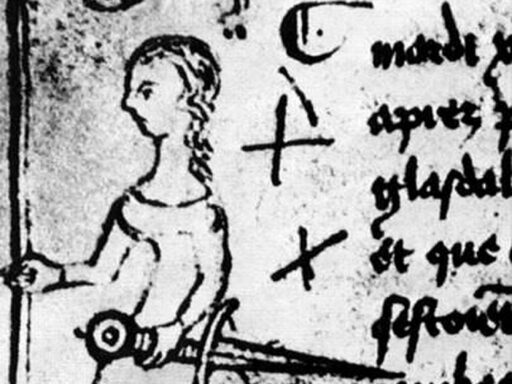

We haven’t found a definitive “Anglo-Saxon Pagan Bible,” which means historians rely on fragments of written records (mostly by Christian monks, who weren’t exactly neutral reporters) and on archaeological finds, which can be as ambiguous as a cryptic riddle. The sources often highlight only those beliefs compatible with or tolerable to the Christian agenda, making them partial at best.

So, what were they actually believing? It’s less useful to think of a fixed set of gods like in Greek or Norse mythology. Anglo-Saxon pagan belief was more flexible. Many historians agree it varied widely—by region, by tribe, even by individual preference. It was a “loose term” covering a wide range of spiritual ideas and rituals.

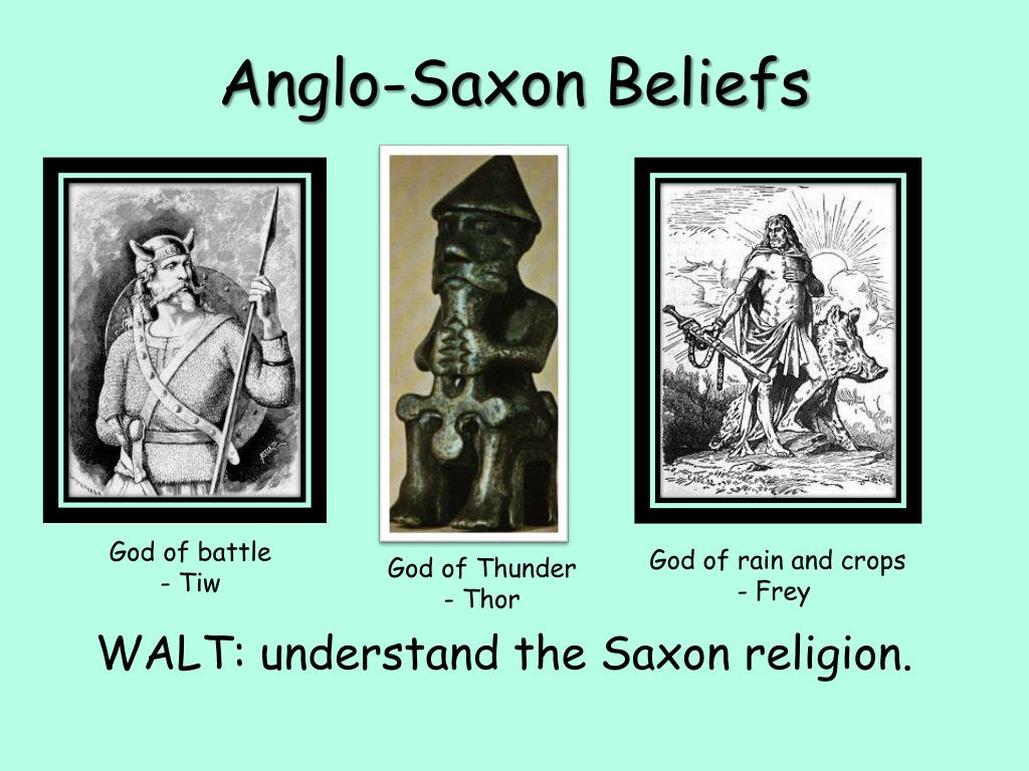

The Spirit World and Totemic Symbols

Imagine the world filled not only with gods but also with mysterious creatures and spirits living around you—in the bogs, mountains, rivers, and ancient burial mounds. Objects like ravens, falcons, wolves, boars, bears, and especially horses held special importance. These animals weren’t just pets or food; they symbolized strength, loyalty, or connection to the spirit world.

Take the raven, for example—seen as a messenger between worlds. Horses had almost sacred significance, often tied to continental Saxon customs. Traces of this reverence for animals and places hint that what we call “worship” might be closer to respect and spiritual connection with natural and supernatural forces.

Worship of Nature and Sacred Sites

Natural features ranked high on their spiritual radar. Streams, wells, bogs, and ponds weren’t just landscapes; they were sacred spots frequented by spirits and possibly worshipped. Some place and river names still preserve echoes of this ancient reverence. Think of them as early “nature shrines.” This kind of spiritual focus contrasts with formal temples or churches common in Christianity.

Material Expressions of Faith

Archaeology offers some of the clearest windows into Anglo-Saxon beliefs. Elaborate cremation burials, boat burials, animal sacrifices, and grave goods buried with the deceased suggest a belief system where death was not an end but a passage. The lavish goods and sometimes weapons included in graves signal the high status of the dead and their hoped-for journey and protection beyond life.

Consider Sutton Hoo, the famed ship burial site. Its contents hint at a blend—items representing warrior honor and perhaps pagan kingship coexist with symbols that might be Christian or hybrid. For instance, a large axe could symbolize a warrior’s power or a role in animal sacrifice. Such finds underline the spiritual complexity before full Christian dominance.

Ritual Sacrifices and Sacred Spaces

The royal site of Yeavering in Northumbria suggests spots dedicated to ritual acts. Archaeologists found numerous ox skulls which hint at possible animal sacrifices—rituals meant to honor gods or supernatural forces. These sacrifices weren’t random; they were serious communal events tied to the wellbeing of people and their leaders.

The Role of Priests and Leadership in Pagan Religion

Unlike the highly organized Christian Church, Anglo-Saxon paganism didn’t have a singular sacred authority. However, this doesn’t mean utter chaos. Some tribal groups likely had their own priests or holy men, probably connected to aristocracy. It’s plausible that a kind of priest-king hybrid existed.

Religious authority could be tied to political power. Gods and totemic animals may have been associated with specific tribes or rulers. This tribal spirituality offered space for pluralism—different beliefs held side by side, allowing for later easy incorporation of Christian elements.

How Did Christian Writers Describe Pagan Beliefs?

Most surviving descriptions of Anglo-Saxon paganism come from Christian writers who were often critical. Bede, the famous 8th-century historian, painted pagan practices as idol worship and magic. For example, he criticized King Edwin for his pagan shrines and highlighted incidents of divination and wizardry as signs of spiritual error.

These accounts deserve caution—they serve as polemical tools more than neutral anthropology. But they confirm that beliefs in magic and supernatural powers were real parts of pagan spirituality, influencing leaders’ decisions and everyday life.

And What About The Dream of the Rood?

This iconic poem beautifully captures the tension and blending between pagan heroic ideals and Christian salvation narratives. Christ appears not just as a divine figure but as a heroic warrior—something deeply resonant to an Anglo-Saxon audience familiar with tales of battlefield glory.

Christ’s crucifixion is portrayed as a battle, with the Cross as a loyal retainer sharing in suffering. This reflects the merging of Germanic heroic values, where loyalty and heroic sacrifice mattered greatly, with Christian theology about redemption and forgiveness.

What does this mean? It means the Anglo-Saxon conversion to Christianity was not a stark break but a creative fusion. They understood Christ through the lens of their warrior culture. The poem itself is a bridge between two spiritual worlds—a reflection of the complex spiritual identity of the time.

Practical Insights for Modern Readers

- Embrace Complexity: Don’t expect uniform beliefs or clear-cut spiritual doctrines in early Anglo-Saxon paganism. Their spirituality was pragmatic and adaptive.

- Look for Syncretism: Early Christianity merged with existing beliefs, not wiped them out. This can inspire reflections on how modern belief systems interact with traditions.

- Respect Nature: The ancient reverence for natural features invites us to appreciate our environment as more than physical space—perhaps as spiritual landscapes as well.

- Consider the Living Spirit World: Anglo-Saxon paganism saw spirits in the landscape—and maybe it’s worth considering what “spirits” mean in today’s context, metaphorically or otherwise.

Final Thought

Anglo-Saxon spiritual beliefs before Christianity were multidimensional, entwined with their social order, natural environment, and worldview—defying simple classification. They did not just worship gods; they engaged with a living tapestry of spirits, symbols, and rituals. The arrival of Christianity brought tension, but also a fascinating synthesis, forming a rich cultural legacy that still captivates us.

Would you find it comforting—or confusing—to live in such a world, where every forest, river, and animal carried divine mystery? Maybe the ancient Anglo-Saxons had it right in seeing the world as alive and sacred, long before churches dotted the landscape.