The doctrine for the windlass arbalest in the 12th century centered on its use as a powerful but slow-firing crossbow, predominantly in siege and battlefield settings. This weapon, commonly termed ballista ad turnum, employed a windlass mechanism to span its large draw weight, enabling it to launch heavier bolts for maximum impact. Its usage required tactical adaptations, such as paired crossbowmen to offset slow reload times, and it utilized specialist heavier bolts, though records often denote generic ammunition. Logistics involved limited personal bolt carriage with dedicated resupply personnel. Archaeological data is scarce, but later medieval evidence informs our understanding of its characteristics and employment.

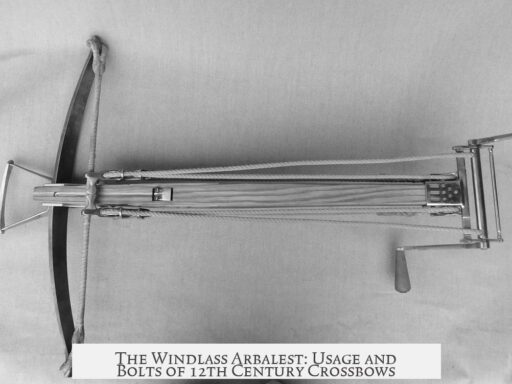

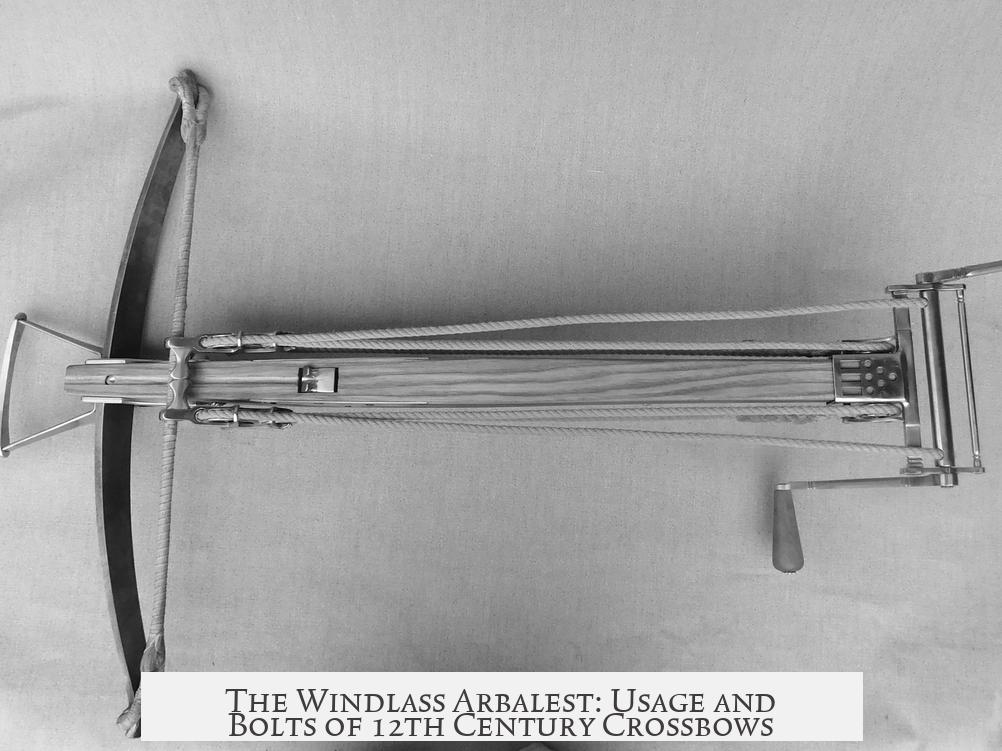

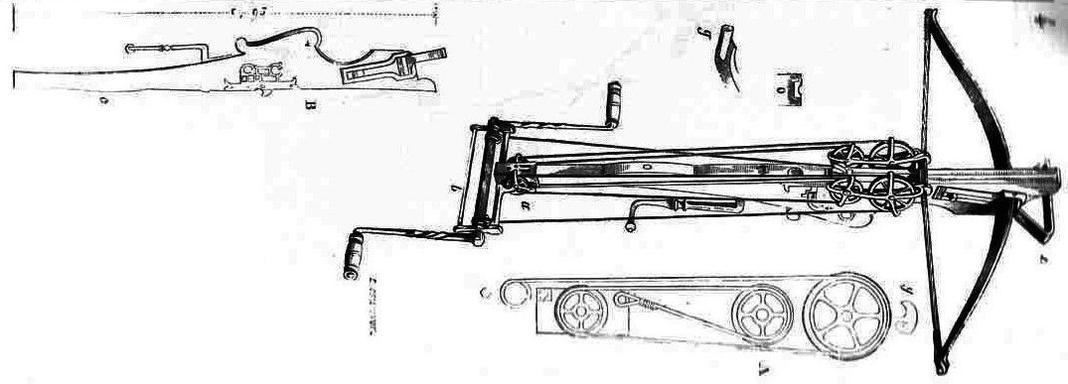

The windlass arbalest, known in Latin as ballista ad turnum, was widely recognized in the 12th and 13th centuries. It differed from lighter hand-spanned crossbows by incorporating a windlass—a mechanical crank—that enabled the user to draw heavier bowstrings that ordinary manpower could not manage efficiently. This system increased the power behind the shot, allowing the crossbow to propel larger, heavier bolts with greater penetrating force, especially useful against armored targets and fortifications.

Primarily deployed during sieges and open battles, the windlass crossbow held a significant role in medieval warfare. Notable historical events such as the Siege of Acre during the Third Crusade and the Battle of Jaffa in 1192 provide concrete examples of its application. At Jaffa, King Richard I’s crossbowmen operated in pairs: one firing while the other reloaded, a tactical adaptation to the windlass arbalest’s slow rate of fire due to the heavy draw weight and mechanical spanning process.

- Siege warfare: The windlass arbalest’s power made it ideal for breaking through fortifications or eliminating enemy defenders at a distance.

- Pitched battles: Its use in open combat involved careful coordination owing to slow reload times.

- Pair tactics: One crossbowman fired while the other rewound the string, enhancing sustained fire during engagements.

Although later medieval warfare saw evolving spanning mechanisms—like cranequins—windlasses coexisted alongside older tools like belt hooks. This coexistence suggests a gradual adaptation rather than an abrupt replacement of arbalest technologies within military units during the late medieval period.

The ammunition for the windlass arbalest was a critical factor in its effectiveness. Bolts used were likely heavier than those fired by lighter crossbows to capitalize on the weapon’s greater power. The physics of the crossbow’s mechanics supports this: while bolt velocity remained similar across different crossbow types, heavier bolts delivered more force on impact due to increased mass.

Evidence from 12th-century records is limited and often non-specific, commonly listing bolts generically. However, documents sometimes specify quantities of bolts allocated to weapons like the ballista ad turnum, implying some form of specialized ammunition existed. G.M. Wilson theorized that while a general type of bolt was used broadly, specialized heavier bolts were also employed for powerful windlass crossbows to maximize performance.

| Period | Typical Bolt Weight Range | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Late Medieval (13th–15th c.) | 60–66 grams | Military bolts likely similar to heavier types used with windlass crossbows |

| Early Modern (15th–16th c.) | 84–100 grams | Heavier bolts suited for high-powered crossbows; provide comparative insight |

| Lighter Bolts | ~40 grams | Used for lighter crossbows with faster firing rates |

Medieval quivers held only 6 to 12 bolts, limiting how many projectiles a crossbowman could carry. To maintain effective rates of fire, armies likely assigned personnel to supply bolts during battles. Crossbowmen probably had to carry a modest initial stock but relied on bulk resupply organized by commanders. This structure emphasized the logistical complexity behind fielding windlass arbalest units.

The limited archaeological evidence for 12th-century bolts is supplemented by later periods where bolt weights have been more systematically recorded. These later samples support the idea that windlass arbalests required heavier projectiles than lighter, hand-spanned crossbows, and that the heavier bolts contributed to their lethality.

Scholarly work from experts like G.M. Wilson and W.F. Paterson provides critical insights into the operational and physical characteristics of the windlass crossbow system. Wilson’s analyses, including his article What’s in a name? One foot and two foot crossbows, clarify terminological and typological distinctions. Paterson emphasizes the physical principle that heavier bolts, rather than faster bolts, defined the augmented power of these weapons. Studies of surviving bolts by Sven Luken and Jens Sensfelder reinforce these conclusions.

- Windlass arbalests were powerful due to large draw weights enabled by windlass mechanisms.

- Heavier bolts, typically over 60 grams, were standard ammunition to maximize impact.

- Slow reloading necessitated paired crossbowmen tactics.

- Ammunition supply required dedicated personnel; individual crossbowmen carried limited bolts.

- Terminological clarity exists around ballista ad turnum as the windlass crossbow.

- Archaeological evidence is limited; understanding draws from later medieval contexts and expert research.

The Doctrine and Typical Usage of the Windlass Arbalest and Its Bolts in the ~12th Century

The windlass arbalest, known in Latin as ballista ad turnum, was a potent and deliberate weapon in the 12th century, used primarily in siege warfare and pitched battles, firing heavier bolts designed to maximize impact despite a slow reload time. It wasn’t a weapon for the impatient or the lone wolf; rather, it demanded teamwork, preparation, and logistics to function effectively on medieval battlefields. Let’s unfold this fascinating story of power, ponderous reloads, and the specialized bolts that marched alongside.

First off, what exactly is this “windlass arbalest”?

Known in contemporary terms as the ballista ad turnum, the windlass crossbow was a mechanically sophisticated beast. Instead of relying on sheer muscle power for spanning—that’s drawing back the string—it used a windlass: a crank or winch system that made drawing the bowstring much easier with its large draw weight. This innovation meant it could launch much heavier bolts farther and with greater force than lighter crossbows, but the trade-off was painfully slow reloading.

How was the Windlass Arbalest Used?

It’s crucial to understand that usage of the windlass arbalest was very much dictated by its design strengths and limits. It was not a quick-firing, snap-shot kind of tool. Instead, it was a deliberate, powerful “punisher” for siege lines and defensive strongholds. Historical evidence points to its involvement in major conflicts such as the Siege of Acre during the Third Crusade (late 12th century) and the Battle of Jaffa in 1192.

At Jaffa, King Richard I’s crossbowmen famously operated in pairs—one shooting and the other reloading the windlass crossbow. This teamwork cleverly compensated for the slow reload time. Such pairing shows us the doctrine around this weapon: it served best in coordinated units rather than isolated marksmen. Imagine a symphony of timing and patience on a smoky battlefield.

Despite technological advances that introduced devices like cranequins (another spanning aid), the windlass didn’t vanish overnight. Historians observe that windlashes, belt hooks, and other spanning methods coexisted well into late medieval warfare periods, which hints at a pragmatic approach to weaponry. Armies used what worked best for each situation.

The Arrows You Don’t Hear About: Bolts for the Windlass Arbalest

The windlass arbalest was an exercise in brute force, but what about the actual ammunition? We know from surviving records that armies ordered hundreds of bolts specifically for ballista ad turnum. Still, these orders often just lumped them under generic ‘bolts,’ implying a mix of specialist and general use ammunition existed.

Why heavier bolts? The revelation here is simple physics: a crossbow’s power is not just about how fast it shoots but how heavy the projectile is. W.F. Paterson, the historian, points out that a more powerful crossbow, like the windlass arbalest, doesn’t increase bolt velocity much but boosts its effectiveness by firing a heavier bolt at similar speeds. That heavier mass translates into greater impact—ideal for piercing armor or climbing walls.

Although direct archaeological finds of 12th-century bolts are sparse, comparisons come from later periods. Bolts in the late medieval era (13th–15th centuries) weighed roughly 60 to 66 grams, early modern bolts (15th–16th centuries) could weigh around 84 grams and some even 100 grams. Light ones tip the scales at about 40 grams. So, bolts for the 12th-century windlass arbalest likely leaned toward the heavier end to match the weapon’s power.

Logistics: More Than Just a Bolt to Load

Imagine a crossbowman lugging a quiver with no more than 6–12 bolts. Hardcore ammo addicts they were not, at least not by medieval standards. Instead, armies had dedicated support personnel whose sole job was to resupply crossbowmen during engagements. This system alleviated the weight burden on the shooter and ensured a consistent flow of ammunition.

Documents from medieval Florence confirm that crossbowmen needed to show up with their primary gear but not necessarily hundreds of bolts. This practical approach hints at a well-organized supply chain, crucial when using slow-reloading windlass arbalests, so that firepower didn’t stall due to lack of ammo.

What’s in a Name? The Windlass, the One-Foot, and the Two-Foot Crossbows

The terminology surrounding windlass crossbows is worth unpacking briefly. The phrase ballista ad turnum generally translates as “windlass crossbow.” Alongside, you find terms like “One-Foot” and “Two-Foot” crossbows, which describe sizes but also hint at variety in design and function across the 12th and 13th centuries.

G.M. Wilson, a former head curator at the Royal Armouries in Leeds, dives deep into these distinctions. He argues that all three (windlass, one-foot, two-foot) could fire generic bolts but sometimes specialized ammunition was crafted to suit particular weapons’ power and size. So, the medieval arsenal was a carefully curated mix of quality and quantity.

Lessons from History: Why the Windlass Arbalest Still Captures Our Imagination

Reflect on the slow but deadly punch of this crossbow type in 12th-century warfare. It demanded patience, strength, teamwork, and logistics. But in the right hands—and battles—it was devastating. The Siege of Acre and the Battle of Jaffa show us these weren’t quaint medieval toys; they were essential tools of war that shaped outcomes.

Modern readers might wonder, wouldn’t firing slower bolts be a drawback? Perhaps, but the heavier bolts could pierce armor and fortifications more effectively than fast, lighter arrows. This trade-off between speed and impact was a tactical choice, reinforcing the principle that medieval warfare was as much about strategy and supply as individual weapon performance.

Practical Tips for Historical Reenactors and Enthusiasts

- Teamwork is key: If you’re reenacting a 12th-century battle using a windlass arbalest, expect crews to work together. One shooter, one loader is historically accurate and practical.

- Heavy bolts for heavy bows: Use heavier bolts to reflect the logistics and performance of these powerful weapons. Expect slower rates of fire but higher impact.

- Supply matters: Have support personnel ready to supply bolts. Quivers won’t hold enough to sustain continuous battle.

- Terminology shapes understanding: Use historical terms like ballista ad turnum to immerse fully and appreciate the weapon’s cultural context.

Concluding Thoughts

The 12th-century windlass arbalest stands as a testament to medieval military ingenuity. Ballista ad turnum wasn’t just a name but a doctrine: powerful, deliberate, and demanding respect. Its heavy bolts packed a punch that compensated for slower firing speeds, fitting seamlessly into siege and battlefield tactics of the time. Teamwork, specialist ammunition, and logistics framed its usage, revealing a layered and sophisticated approach to warfare.

Despite limitations in surviving artifacts and records, careful scholarship, and comparisons from later medieval periods shed light on this formidable weapon. It remains an excellent case study of how medieval armies balanced technology, manpower, and strategy to turn the tide in their favor.

So next time you hear “crossbow,” remember that not all bolts zip through the air with the same breathless speed. Some took their time, hitting like thunder while making you wait. The windlass arbalest? It was exactly that kind of storm.