Queen Victoria’s relationship with her children was complex and often strained. She demanded obedience and viewed herself as the ultimate authority in their lives. This dynamic led to tension, especially with some children who resisted her strict control or failed to meet her high expectations.

Victoria had nine children with Prince Albert. Though she bore many children, her motivation was driven largely by her sexual attraction to Albert, not by a maternal desire for babies. Victoria was known to be intolerant of infants but grew fond of her children as they developed distinct personalities. She required submission not only as a queen but within her family. Dissent or disagreement with her views often damaged her relationships.

Her firstborn, Albert Edward, later King Edward VII, had a famously difficult relationship with his mother. Victoria imposed very high standards on him from birth, expecting him to emulate his parents and not follow the example of her Hanoverian uncles, who were mocked for their indulgences. Despite his intelligence and charm, Bertie could not live up to these expectations.

Victoria’s strict upbringing of Edward included rigorous education and firm control. After Prince Albert’s death from typhoid, Victoria blamed Edward for his early indiscretions, which worsened their bond. When Edward contracted typhoid later, their relationship briefly improved, but old tensions eventually resurfaced.

Victoria’s daughter, Victoria, the Princess Royal, had a better relationship with her parents. She conformed to family rules and fulfilled expectations as the dutiful eldest daughter. Her obedient nature contrasted with the rebelliousness of some of her siblings.

Alice, another daughter, was strong-willed like her father. After her 1862 marriage, she sometimes argued with Victoria, showing the occasional clash between mother and child.

Alfred, once favored as the “good” son, saw his relationship with Victoria decline during his adult years. His naval career took him abroad for long periods, and his reportedly brusque manner displeased the queen.

Helena, sometimes considered dull, stayed close to her mother after marriage to oversee household matters and carry out Victoria’s directives. She was not rejected but lived under her mother’s watchful eye.

Louise, the artistic child, experienced conflicts with Victoria later in life. Her sharp and bitter demeanor contributed to tensions, reflecting more on Louise’s character than on Victoria’s.

Arthur managed to maintain a good relationship by accepting Victoria’s need for control. His compliance allowed smoother interaction with the queen.

Leopold, the sickly and unattractive baby, displeased Victoria early on. His health forced him into the background, which generated resentment. His life was marked by enforced control until his premature death.

The youngest, Beatrice, was initially spoiled. After Prince Albert’s death, Victoria clung to Beatrice more tightly, controlling her personal life, particularly by opposing Beatrice’s desire to marry. Victoria depended on Beatrice to care for her in widowhood, which caused further friction.

The underlining issue in Victoria’s relationships was her role as queen, not merely as a mother. She ruled from age 18 and grew up in a culture demanding lifelong deference from children. While most families might allow some flexibility in parent-child roles, Victoria could not. To her, as the reigning monarch and Empress of India, obedience was mandatory.

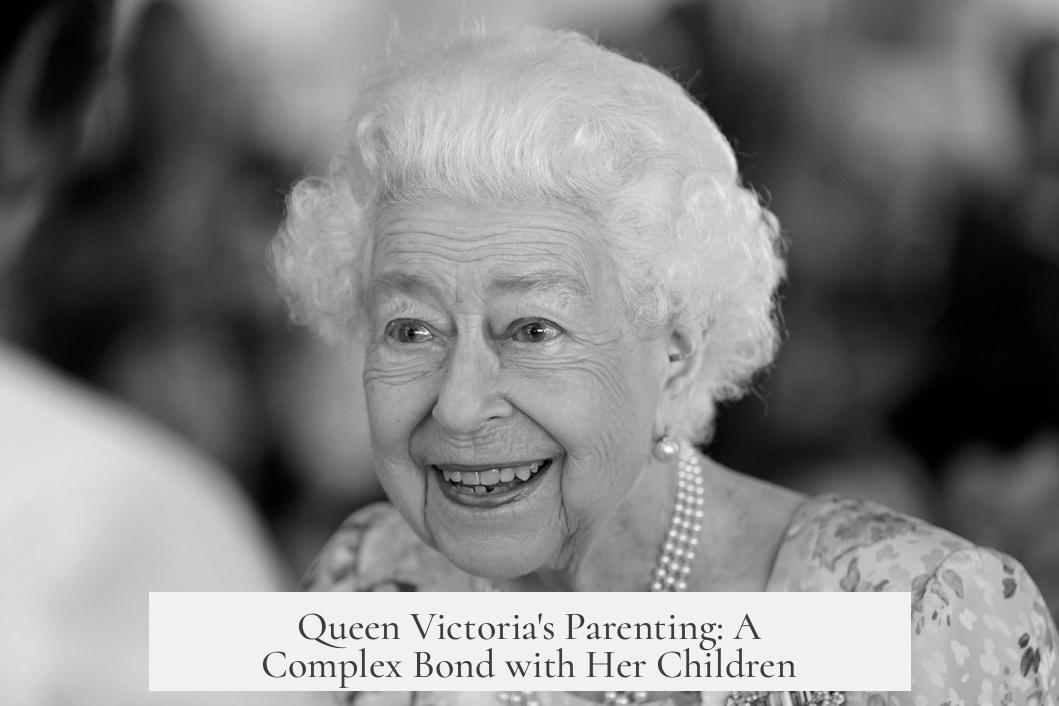

| Child | Relationship with Victoria |

|---|---|

| Albert Edward (Bertie) | Difficult; high expectations, blamed for Prince Albert’s death, brief reconciliation |

| Victoria, Princess Royal | Good; obedient and conforming |

| Alice | Occasional arguments; strong-willed |

| Alfred | Favored early; distant and brusque in adulthood |

| Helena | Kept close to mother; perceived as dull |

| Louise | Artistic; conflicted with mother later |

| Arthur | Compliant; accepted Victoria’s control |

| Leopold | Resented control; sickly and distant |

| Beatrice | Spoiled young; tightly controlled in adulthood |

- Victoria’s relationships with her children were shaped by her role as monarch who demanded submission.

- Her eldest son, Bertie, struggled under impossible standards and their bond remained strained.

- Some children conformed, some rebelled, but few had entirely smooth relations with her.

- Her late husband’s death intensified control, especially over youngest daughter Beatrice.

What Was Queen Victoria’s Relationship with Her Children Like?

Queen Victoria’s relationship with her children was, frankly, complicated and often strained. As the sovereign ruler and a mother, she juggled her royal duties with family life in a way that frequently caused friction. For Victoria, motherhood wasn’t about cuddly family moments but about control, obedience, and meeting her very high standards.

Let’s dive into the dynamics that made this relationship so famously intense—and a touch dysfunctional.

Why So Many Children? Hint: It Wasn’t Pure Maternal Instinct

Victoria is known for having nine children, a fact that might make you picture a warm, bustling family life full of laughter and play. Not quite. In reality, her many offspring were largely the byproduct of a fiery marital attraction to her beloved Prince Albert. Oddly enough, she didn’t adore babies all that much. It was only when her children grew older, developing distinct personalities, that she started to tolerate and appreciate them.

Victoria’s attitude toward her children was firmly rooted in discipline and authority. Submission to her viewpoint wasn’t just asked for—it was demanded. Exception? Her husband Albert, who had a unique place as her trusted partner.

Bertie: The Eldest Son Who Just Couldn’t Measure Up

Albert Edward (aka Bertie, later King Edward VII) had one of the rockiest relationships with his mom. From the moment of his birth, Victoria placed enormous expectations on him. He was supposed to be the perfect heir, embodying everything his mother and father stood for. Spoiler alert: he wasn’t.

Young Bertie faced a grueling, strict education meant to keep him on the royal straight and narrow, a jab at his hoity-toity Hanoverian uncles who had scandals aplenty. Yet, as history shows, Bertie’s later lifestyle wasn’t exactly a crown jewel of virtue.

After Prince Albert died of typhoid, the downward spiral worsen for Bertie and his mother. She blamed him for Albert’s passing—because Albert had traveled to reprimand Bertie over an affair with an actress. Imagine the awkward family hangout after that.

There was a glimmer of hope for a thaw in 1871, after Bertie faced his own health scare with typhoid. For a moment, he seemed to grow up. But—spoiler again—he reverted to his old ways. The tug-of-war with Victoria carried on.

The Other Siblings: A Mixed Bag of Temperaments and Tiffs

- Princess Vicky, the Princess Royal: The good girl who followed the rules and got along better with her parents. Think of her as the reliable older sister in the family.

- Alice: Strong-willed and self-demanding like her dad. She didn’t shy away from arguing with Victoria, especially after her 1862 marriage.

- Alfred: Once Victoria’s favorite, his naval career turns brought a gruff demeanor she found grating. Doting mom turned frown.

- Helena: Not exactly the star, seen as dull and “kept” around to help Victoria manage household affairs, especially after marriage.

- Louise: The artistic rebel who clashed with Victoria because of her “sharp and bitter” manner—more about Louise’s personality than Victoria’s.

- Arthur: The dutiful son who simply accepted Victoria’s need for control. Compliance was his survival strategy.

- Leopold: The sickly baby who never escaped Victoria’s disapproval. Forced into the shadows for health and family image, he resented this until his early death.

- Beatrice: The baby of the family, spoiled at first, she became the focus of Victoria’s intense need for a caretaker after Albert’s death. Victoria’s grip tightened when Beatrice wished to marry. Spoiler: mom’s not thrilled.

What Drove Victoria’s Strict Parenting Style?

Here’s a question worth pondering: how do you balance being queen of the United Kingdom and a mother? Victoria didn’t. At least not by today’s standards. She ruled with an iron fist, expecting the same from her children.

She believed everyone owed her obedience because she was the monarch. In her mind, family was an extension of the kingdom. Children weren’t equals. They were subjects who must comply endlessly with her wishes.

“For most families, the parent-child dynamic occasionally loosens. But not for Queen Victoria. Her crown meant that family compliance was a state affair.”

This made it tough for her kids to develop independent selves without bumping heads. The queen’s imperious style clashed with their natural desires to find their own paths—resulting in lifelong tensions.

Takeaways and Reflections

Looking back, Victoria’s relationships with her children reveal how absolute power seeps into personal life. She expected the same unquestioned obedience at home as she did across the empire.

The mix of high expectations, personal grief (notably around Albert’s death), and Victorian-era values created an environment where love looked more like duty and discipline than warmth and openness.

It begs the question: If you were raised by a queen who demanded submission as a form of respect, how would you fare? Would you conform or push back? Victoria’s kids tried both—with varying success.

One thing is undeniable: Victoria’s story is a perfect reminder that being a great ruler didn’t guarantee being an easy parent. Her children inherited not only titles but the heavy weight of their mother’s towering presence, often defined more by command than cuddles.

And maybe, in that mix of duty and disappointment, lies the human story behind one of history’s most iconic monarchs.