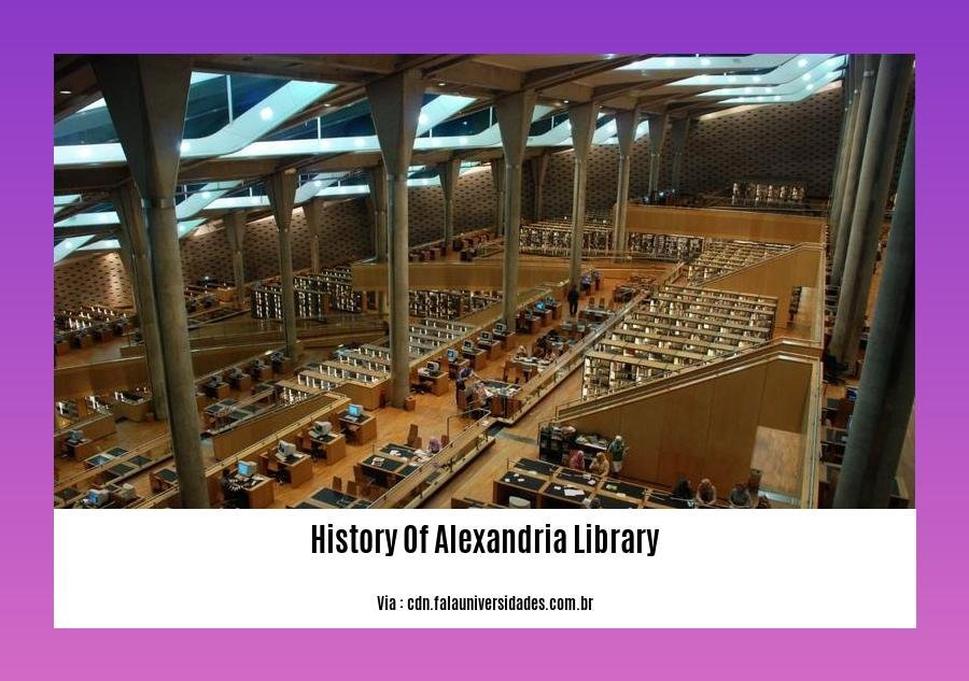

The Library of Alexandria was special largely because of the myths and symbolism that developed around it, rather than its actual uniqueness or historical significance in antiquity. While it remains famous today, the library was one among many ancient libraries, and its importance in practice was limited. The legend of the library stems from modern interpretations rather than verified historical evidence.

Ancient Mediterranean society hosted hundreds of libraries during the Roman and Hellenistic periods. Examples include the Palatine Library and Portico of Octavia in Rome, and smaller private collections scattered even in modest towns like Como and Timgad. The Library of Alexandria was not alone in housing extensive collections of texts. Many other repositories contributed to preserving knowledge and were integral in the culture of the time.

In Egypt itself, the Alexandrian library’s importance was not paramount. A surviving manuscript of Aristotle’s Constitution of the Athenians originated from Hermopolis rather than Alexandria. Numerous Greek texts have come from Oxyrhynchus, another Egyptian city. This suggests that knowledge and book trade thrived across multiple centers, not concentrated exclusively in Alexandria. The existence and operation of many libraries meant that the loss of one large library did not significantly disrupt the preservation of knowledge.

The survival of ancient texts depended more on governmental support and continuous copying than the fate of any single library building. None of the hundreds of libraries from antiquity survive intact today. For example, the Palatine library endured several devastating fires but continued to exist for some time thanks to official support. The transition between writing formats and scripts—such as the change from scroll to codex between the second and fourth centuries and the shift from uncial to minuscule script around the ninth and tenth centuries—caused the greatest loss of ancient texts. These systemic changes had far more impact than any single catastrophic event like a library fire.

The modern myth of the Alexandrian Library as a unique, irreplaceable treasure trove of all ancient knowledge is a recent phenomenon. Until the late twentieth century, many scholars and thinkers regarded the library more as a symbol of excess or vanity than of learning. Seneca, a first-century writer, described it as “studious luxury” collected more for spectacle than for genuine study. Later intellectuals, from seventeenth-century writer Thomas Browne to eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon, often viewed the library’s destruction skeptically or as a cautionary tale about misplaced values.

The popular myth gained significant momentum after Carl Sagan’s 1980 television series Cosmos. Sagan’s portrayal connected the library with the philosopher Hypatia and depicted its destruction as a catastrophic loss of knowledge caused by religious conflict. This narrative, though widely embraced, is not supported by historical evidence. The so-called “Great Library of Alexandria” and its dramatic destruction are inventions popularized through modern media, overshadowing the historical reality.

In fact, the use of the term “Library of Alexandria” with a capital “L” and phrases like “Great Library” ballooned post-1980, highlighting how mythmaking shaped public perception. The library’s famed status today parallels how stories amplify its symbolism of lost wisdom rather than an accurately documented unique institution.

| Aspect | Reality | Myth |

|---|---|---|

| Uniqueness | One among many libraries in antiquity | The sole or unparalleled repository of ancient knowledge |

| Impact of Destruction | Loss typical of any library fire, with texts preserved elsewhere | Massive, irreplaceable loss leading to a knowledge dark age |

| Cultural Role | Part of a network of scholarly centers | Symbol of ultimate scholarship and enlightenment |

| Association with Hypatia | No historical evidence linking her directly to the library | Hypatia as a librarian victimized in the library’s fall |

Key takeaways:

- The Library of Alexandria was not unique; many libraries existed throughout antiquity.

- Its reputation as a massive, irreplaceable collection primarily results from modern mythmaking.

- The loss of texts depended more on material transitions and continual copying than on a single catastrophic event.

- The library symbolizes lost knowledge but historically was one node in a broader scholarly network.

- Popular culture, especially post-1980, has amplified myths, overshadowing actual historical evidence.

What Made the Library of Alexandria So Special?

The Library of Alexandria was not as unique or irreplaceable in antiquity as many believe; its fame is mostly a modern myth shaped by symbolism and storytelling rather than historical facts. This might come as a surprise if you thought it was the all-mighty mother of all ancient libraries. So, what made it so special? Let’s unpack this fascinating mix of fact, fiction, and human tendency to magnify losses.

First off, let’s clear the air: Alexandria’s library wasn’t the only library around. Far from it.

Not the Lone Bearer of Knowledge

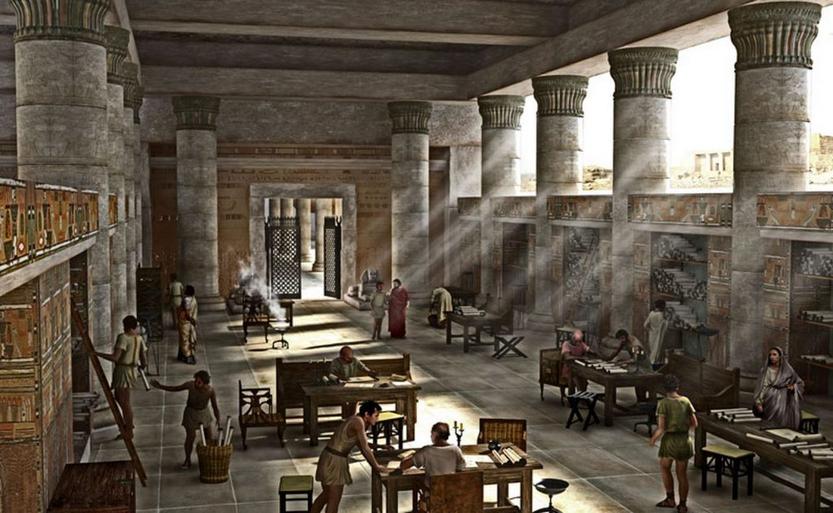

Imagine the ancient Mediterranean as a vibrant literary marketplace filled with hundreds of libraries. Rome alone boasted a dozen notable libraries — names like the Palatine Library, Portico of Octavia, and libraries in the Baths of Caracalla come to mind. And this wasn’t just a Roman thing. Libraries popped up in cities you might not expect — from *Timgad* in Algeria to *Prusa* in Turkey.

Even within Egypt, Alexandria’s library wasn’t the ultimate source for ancient Greek texts. Texts like Aristotle’s Constitution of the Athenians were copied far from Alexandria, in places like Hermopolis, showing that knowledge had many homes.

Many ancient Greek manuscripts we have today actually come from *Oxyrhynchus*, not Alexandria. It turns out, Alexandria was just a large fish in a pond full of other fish—not the vast ocean itself.

The Myth of Catastrophic Loss

You might have heard that when Alexandria’s library burned, humanity lost a treasure trove of knowledge forever. Not exactly. While fires did happen, the survival of ancient texts had much to do with continuous copying and the support of governments rather than a single catastrophic event.

For instance, Rome’s Palatine Library suffered multiple fires but survived longer due to governmental backing. Without that support, no library lasts long, no matter how grand.

Think of ancient books like a game of “telephone”: texts survived only when scribes or scholars made fresh copies. If copying stopped, the text vanished.

Transitions between formats caused far more loss than fires ever did. When scrolls gave way to codices (like ancient e-books upgrading to real books), many works didn’t make the leap. Later, shifting from uncial to minuscule script in the 9th to 10th centuries also led to devastating losses.

Changing Perceptions: From Vanity to Symbol

For centuries, the Alexandrian library was viewed less as a beacon of knowledge and more as an extravagant symbol of vanity and royal excess.

“Forty thousand books burned at Alexandria: let someone else praise it as a beautiful monument of royal opulence… it was studious luxury — no, not even studious, since they didn’t collect books for study, but for a spectacle.”

Seneca’s skepticism in the 1st century CE sets the tone. In later centuries, writers like Rousseau took this further, suggesting that destroying the library might even have been a *fine* act in a twisted moral fable.

So how did it become the beloved victim of cultural loss—in other words, *the* great tragedy—in modern times?

Modern Mythmaking and the Rise of the “Great Library”

Enter Carl Sagan and his 1980 TV series Cosmos. Sagan didn’t just popularize the Library of Alexandria; he gave it a mythic aura. He linked the demise of renowned scholar Hypatia to the library’s destruction (historically false). The library was recast as a unique, irreplaceable hub of ancient wisdom obliterated by religious fanaticism—another twist of fiction layered on reality.

This reshaping had a massive impact: the phrase “Great Library of Alexandria” gained capitalization and cultural weight it never had historically. The loss of the library became symbolic of humanity’s lost potential.

Google Ngram data shows this surge in popular awareness coinciding with Sagan’s portrayal, proving how media shapes our understanding of history.

So, What Really Made the Library Special?

- It wasn’t unique or unrivaled in the ancient world.

- The real tragedy wasn’t just its loss but the widespread loss of cultural knowledge due to changing practices and formats over centuries.

- Its fame grew mainly through myth and symbolism, especially in the last few hundred years.

- Libraries across the ancient world, combined with repeated copying and preserving texts, ensured that knowledge didn’t hinge on one single collection.

- The narrative of a burning library blocking knowledge feeds modern fears about the fragility of intellectual heritage.

Think about it: no ancient library exists intact today. The preservation of culture always depends on human effort over time, not on physical buildings alone.

Lessons and Reflections

What can we learn here? Don’t put all your books in one basket—literally or figuratively. Books, ideas, and knowledge thrive in networks, not in isolated vaults.

The myth of the Alexandrian library teaches us a valuable lesson about history—sometimes, what’s remembered reveals more about our hopes and fears than about past realities.

Modern libraries, digital archives, and even your local library face similar challenges. How can we ensure knowledge survives? By copying (digitizing), sharing, and supporting preservation efforts, much like ancient scribes did, but on a massive, global scale.

And if you ever feel bad about losing a book, remember: it’s not the end of the world unless *all* copies vanish — in which case, maybe the Alexandrian library has a lesson or two for us.

Curious for More?

Want to dive deeper? Check out this thorough answer about the library’s symbolic history or explore how ancient books were transmitted. Scholars like R. S. Bagnall and L. Casson write extensively on the broader ancient library landscape.

In the end, what made the Library of Alexandria special was not its uniqueness but its power to inspire imagination and caution—reminding us that preserving knowledge requires constant care, effort, and perhaps a little bit of modern myth-making to keep the story alive.