The Byzantine Empire slowly lost its territories and influence during the Medieval Era due to a mix of internal weaknesses, external pressures, economic challenges, and religious divisions. Each factor contributed significantly, collectively weakening the empire over centuries.

Internal difficulties played a crucial role in territorial decline. The empire’s treasury suffered greatly after Justinian’s campaigns aimed at reconquering lost Western Roman lands. These campaigns drained resources while the Byzantine military faced constant demands on multiple fronts: Italy, the Balkans, and Mesopotamia. Further compounding the strain was the devastating impact of the Black Death in the 6th century, known as Justinian’s Plague. This epidemic severely reduced the urban population, weakening both economic and military capacities. The plague continued to afflict the empire intermittently for centuries, hindering recovery and growth.

Leadership issues compounded these troubles. Many Byzantine rulers lacked long-term vision and often prioritized personal power over state stability. This resulted in frequent civil wars, infighting, and rebellion among generals. The empire lacked clear succession laws, unlike its Muslim neighbors, leading to power struggles that fragmented authority. The Battle of Manzikert in 1071 stands out as a turning point where the empire lost the fertile Anatolian interior. This loss of crucial manpower and tax revenues left the empire vulnerable. Corruption and nepotism thrived within the military and government, eroding institutional effectiveness. Ironically, the military was deliberately downsized in the 11th and 12th centuries because it threatened the emperor, despite rising external threats.

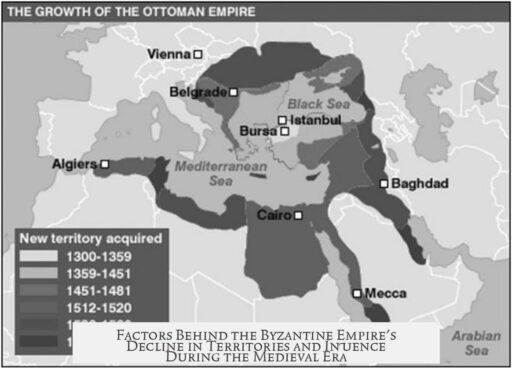

Externally, the empire faced relentless pressures. The prolonged wars with the Sassanian Persians exhausted resources and manpower. Soon after, the sudden rise and unification of Islamic Caliphates overwhelmed weakened Byzantine borders. Muslims conquered much of the Sassanian Empire and swiftly took Byzantine territories in the Levant, Egypt, and North Africa. These losses cut off critical trade routes and grain supplies, such as Egypt’s Nile wheat, which had sustained large cities and military strength.

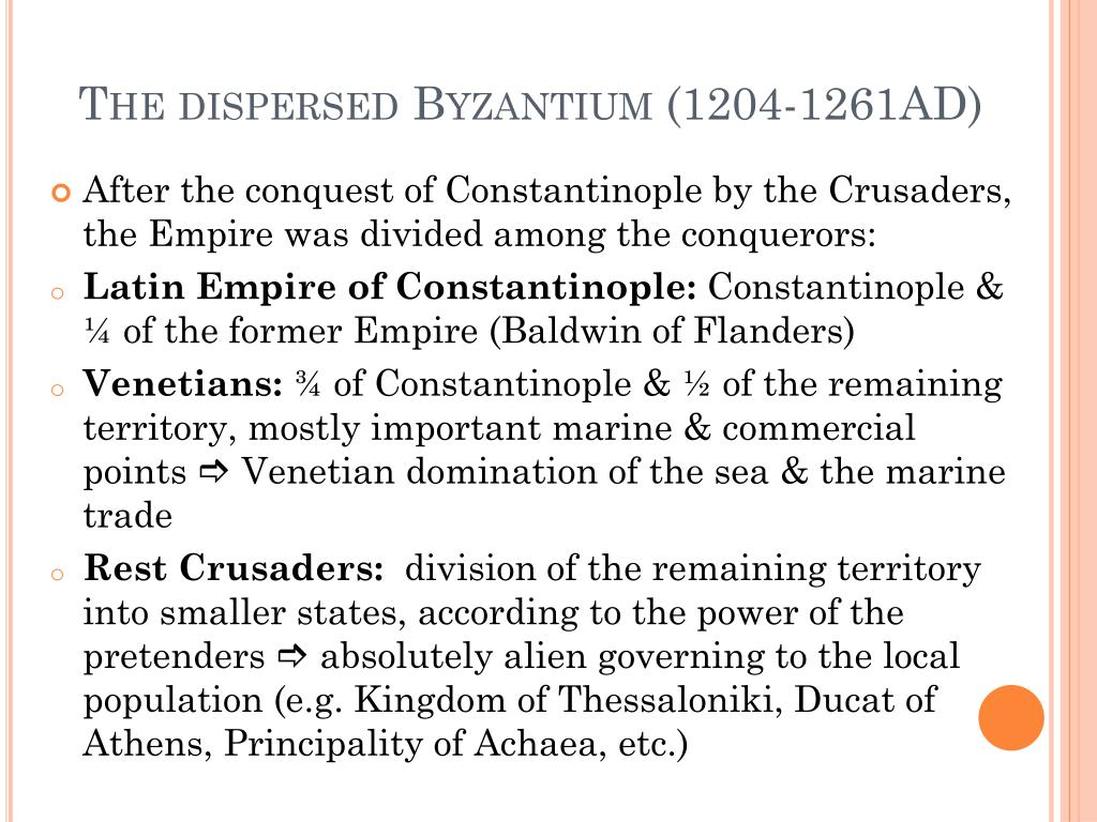

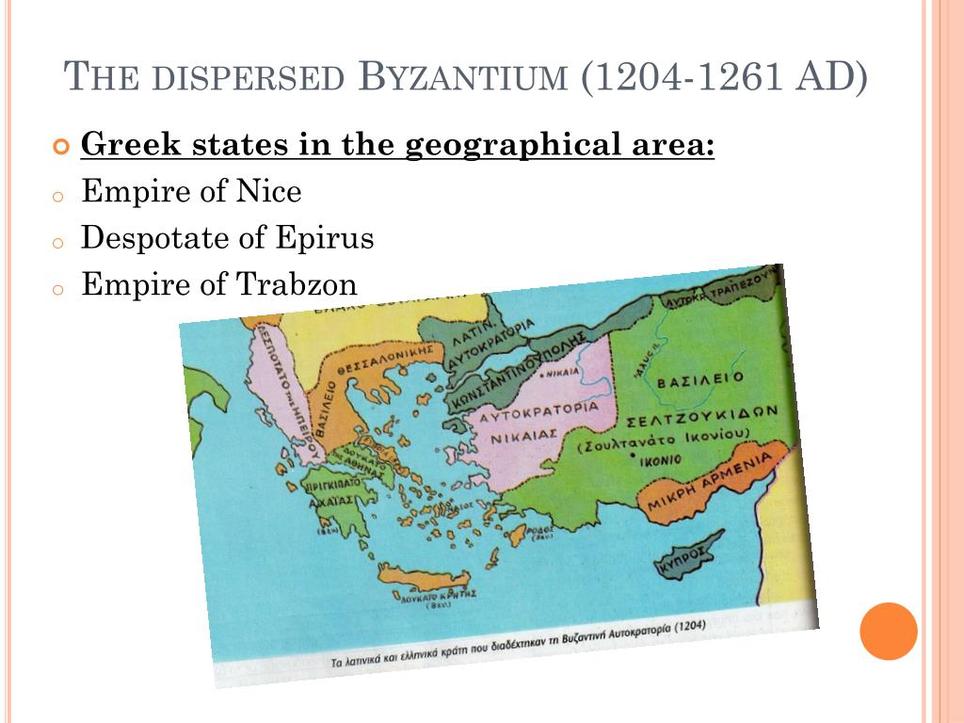

The empire also contended with barbarian raids, Turkish invasions, and the establishment of new powers like the Normans and Venetians, which chipped away at its holdings. The Crusades, particularly the Fourth Crusade, dealt a devastating blow when Crusaders sacked Constantinople in 1204. Instead of restoring Byzantine lands, the Crusades fragmented the empire politically and economically, creating Latin states within former Byzantine territory. This event worsened relations between Eastern and Western Christianity, deepening cultural rifts.

Economic decline was another key factor. The rise of Islamic states disrupted traditional East-West trade routes that Byzantium controlled for centuries. Starting in the 11th century, the empire increasingly relied on Italian maritime republics such as Venice, granting them advantageous trade privileges in exchange for naval support. This drained Byzantine naval power and allowed Italian merchants to dominate trade, weakening economic independence. The loss of Egypt further deprived Byzantium of vital agricultural exports necessary to feed and fund the military and urban populations.

Religious and cultural divisions added to stability challenges. Doctrinal disputes, especially the Monophysite controversy, alienated important eastern provinces like Egypt and Syria. The empire’s inability to unify diverse religious groups under Orthodox Christianity weakened local loyalty. Many of these regions were more accepting of Muslim rule after Byzantine authority waned. The schism between the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches fractured Christian unity, making Western aid unreliable and fueling mistrust that worsened with the Crusades.

| Key Factors | Impact on Byzantine Decline |

|---|---|

| Internal Weaknesses | Depleted treasury, plague, leadership failures, civil wars, corruption, military downsizing |

| External Pressures | Muslim conquests, wars with Persians, Turkish invasions, Crusader sacking |

| Economic Challenges | Loss of trade routes, dependence on Italian merchants, loss of Egypt’s resources |

| Religious Divisions | Doctrinal disputes, weakened control over eastern provinces, East-West church schism |

Consolidated, these elements created a cycle of decline. The Byzantine Empire’s ability to govern and defend its vast territories eroded over time. Internal discord sapped resources needed to fight external foes. Losses to emerging forces reduced economic base and manpower. Fragmentation of religious and cultural cohesion prevented unified resistance. Despite occasional recoveries, the empire never fully regained its earlier strength.

- Military and financial exhaustion from prolonged multi-front wars and plague weakened the empire.

- Incompetent rulers and civil wars destabilized governance and defense mechanisms.

- Emergence of unified Muslim forces led to rapid loss of vital eastern territories.

- Economic dependence on Italian states undermined naval power and trade control.

- Religious divisions alienated key provinces and fractured Christian unity.

- The Fourth Crusade’s sack of Constantinople irreparably damaged Byzantine political cohesion.

What Made the Byzantine Empire Slowly Lose Its Territories and Influence Throughout the Medieval Era?

The Byzantine Empire gradually lost its territories and influence due to a powerful mix of internal weaknesses, relentless external pressures, economic challenges, and deep religious divisions. This slow decline stretched across centuries, a perfect storm of factors that chipped away at a once-mighty empire. Let’s unpack this fascinating tale in more detail.

Imagine a grand chessboard where the Byzantine Empire sits, but its pieces are slowly being drained by its own internal fights and external enemies lurking around every corner. It’s a story of bluff, bravado, and gradual erosion rather than a sudden collapse.

Internal Weaknesses: The Empire’s Achilles’ Heel

The first domino to fall was the empire’s internal problems. Initially, after splitting from the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire (later called Byzantine) reconquered vast lands under Emperor Justinian. But those victories came at a steep price: the empire’s treasury was drained dry.

A series of brutal wars over multiple fronts – Italy, the Balkans, Mesopotamia – spread resources thin. The empire wasn’t strong enough to fight on all fronts simultaneously. Instead of sacrificing one front to save another, it stubbornly held all, weakening itself in the process.

To add insult to injury, the Black Death struck not once but repeatedly. Perhaps fewer people know about Justinian’s Plague, the 6th-century ancestor of its more famous cousin in the 14th century. For an urbanized society like Byzantium, this plague was brutal. It decimated the population, drained manpower, and undermined the economy. The empire’s neighbors, like nomadic Arab tribes, suffered less from the plague, giving them a demographic advantage.

Picture the empire trying to patch battle wounds while its citizens are dropping like flies. That sets a grim scene for survival.

On top of this was political chaos. Many emperors, distracted by personal ambitions, ignored the empire’s long-term needs. Instead of building lasting strategies, they played power games. Civil wars erupted, infamously exemplified after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. This battle, where the Turks routed the Byzantines, resulted in the loss of Anatolia’s fertile lands—a blow from which the empire never truly recovered. Anatolia was the empire’s breadbasket, providing both tax revenue and manpower.

Without stable succession laws, rivalry festered among heirs and generals. Literally, whoever had the biggest army won the throne. This turmoil weakened the state from inside more than any external enemy could.

Moreover, Byzantine corruption thrived in military and government ranks. The empire’s sophisticated military training system ironically bred nepotism and cronyism. Power blocs emerged within the army, creating distrust and inefficiency. Even as armies dwindled, emperors feared the military’s growing power more than the Turks. So they deliberately cut military strength, leaving the empire exposed as threats increased. That’s like firing your security guards because you think they’re going to steal from you—in the middle of a burglary spree.

External Pressures and Conflicts: The Empire’s Enemies Circle Closer

Playing defense on multiple fronts is exhausting, and the Byzantines faced some ruthless adversaries. The rise of Islam in the 7th century unified peoples who had previously been divided. The new Muslim armies quickly conquered Byzantine and Sassanid Persian territories with speed and cohesion the Byzantines weren’t prepared for.

The Byzantine-Sassanid wars preceding the rise of Islam had drained both empires of blood and resources. When Heraklius finally defeated Persia, both sides were left vulnerable. The freshly formed Caliphate capitalized on this weakness, seizing most of the Persian Empire’s lands and large swaths of Byzantine territory.

The empire then found itself constantly under attack—whether from Arabs, Turks, Pechenegs, or Cumans. Every border was a battlefield. It’s challenging to maintain control when your enemies gather like hungry wolves at every edge.

Perhaps the most striking blow was the 1071 Battle of Manzikert. The defeat meant the loss of central Asia Minor, Anatolia, which was rich farmland and a key recruitment zone for armies. Without this, the empire rapidly lost its capacity to sustain itself militarily and economically.

The Crusades, originally perceived as Western reinforcements, complicated matters further. Emperor Alexios I Komnenos called on the West for help to reconquer Anatolia but got more than he bargained for. Instead of just mercenaries, large Crusader armies had their own agendas.

The infamous Fourth Crusade (1204) resulted in Crusaders sacking Constantinople itself, carving out Byzantine lands for themselves. This not only reduced territory but deepened the distrust between East and West. The schism between Orthodox and Catholic churches grew wider, alienating potential allies. Byzantine citizens post-1204 reportedly preferred Turkish rule to Latin control—a stark testament to how bitter the wounds ran.

Economic Factors: When Wealth and Trade Flee

Trade was the lifeblood of the Byzantine economy. Constantinople sat at the crossroads of land routes to Asia and the Mediterranean, reaping riches. However, as Islam advanced, many eastern trade routes fell under Muslim control, cutting Byzantium off from lucrative markets.

In the 11th century, desperate for naval support, Byzantium granted Italian city-states like Venice exclusive trade privileges. Initially strategic, this became an economic Trojan horse. Italian merchants soon dominated Byzantine trade, and the empire’s own navy collapsed under their influence. Venetians grew powerful within the empire’s economic sphere, leading to tension and resentment, culminating in the violent massacre of Latins in Constantinople in 1182.

Another economic blow was the loss of Egypt in the 700s. The Nile was crucial as a wheat source, supporting large urban populations. Roman and Byzantine empires had thrived largely because of granaries supplied by Egypt’s fertile lands. Losing Egypt meant the empire could no longer easily feed or sustain large cities, weakening urban growth and economic stability.

Religious and Cultural Divisions: The Empire’s Internal Rift

Religious disunity played its part in fracturing the empire’s cohesion. Early on, divisions like the Monophysite controversy created deep splits within Christian communities, especially between the Orthodox Christians of Constantinople and Miaphysite Christians in eastern regions.

The empire tried to grant autonomy to some of these groups but never fully resolved the tensions. When the Muslim conquests swept into Egypt and the Levant—areas with discontented Miaphysite populations—there was minimal resistance. Religious divisions thus soft-pedaled the loss of these vital provinces.

These religious rifts also influenced diplomacy and military alliances. The Great Schism of 1054 formally divided the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. This created suspicion and hostility between Byzantium and the Latin West, hampering cooperation at critical times, especially during encounters with the Crusaders.

Lessons and Reflections

The Byzantine Empire’s decline is a compelling story of how a once-great power can be undone not by a single cataclysm but by a slow and steady erosion of strengths paired with mounting pressures from within and without.

- Internal instability sapped its ability to respond effectively to threats.

- Exhausting wars depleted its resources long before new enemies arrived.

- Economic domination by Italians slowly strangled its fiscal independence.

- Religious and cultural splits fractured society and weakened unity.

- Relentless enemy pressures tightened the noose, making recovery difficult.

Thinking about this, one wonders: Could better succession laws have changed history? Would a stronger navy earlier on have kept Western mercenaries in check? Perhaps a bit of humility toward rivals and an eye for unity over factionalism might have slowed the decline.

Regardless, the Byzantine Empire’s resilience for over a millennium—especially after the fall of its Western counterpart—is remarkable. It was the last bastion of Roman governance, law, and culture in medieval Europe and the Near East. Even as it lost land, it shaped medieval society with its art, learning, and diplomatic savvy.

In conclusion, the Byzantine Empire’s slow loss of territory and influence was not the work of a single factor. It was an intricate web of internal missteps and external challenges, economic setbacks, and religious strife. This layered decline offers vital insights into the complexities nations face when balancing power, culture, and survival.

And as history teaches us, empires often fall not just due to enemies outside their walls but also because of struggles within.