The potato originates from the Andean region of South America, where indigenous peoples began cultivating it over 4,000 years ago. Initially domesticated by 2,000 BCE, the crop played a crucial role in Andean agriculture and culture. Its journey from the remote Andes to global staple status unfolded over centuries, shaped by exploration, adaptation, and promotion.

The earliest evidence of potatoes dates back to around 10,000 BCE in southern Chile. Over time, ancient South American farmers domesticated different wild varieties, focusing mainly on potatoes grown from seeds rather than tubers. This seed-based cultivation encouraged enormous genetic diversity, leading to the vast array of potato types known in the region—over 4,000 varieties thrived throughout Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, and Chile.

The domestication process distinguishes early Andean potatoes from the ones familiar worldwide today. Early farmers planted from true seeds, harvested from pollinated potato flowers rather than cutting and planting tubers. This practice maintained genetic variation, making them more resilient and adapted to different mountain microclimates. In contrast, the later European potato predominantly propagated by planting tuber segments, reducing genetic diversity.

The introduction of potatoes to Europe occurred during the Columbian Exchange following Christopher Columbus’s voyages. In 1532, Spanish conquistadors, led by Francisco Pizarro, encountered native populations consuming small round potatoes. They carried a variant called Solanum tuberosum back to Spain. From there, potatoes spread throughout Europe, reaching the Canary Islands, France, and the Netherlands by the late 16th century. However, only a limited subset of Andean varieties made it overseas, mainly the cloned strain favored by Europeans.

Potatoes remained a minor staple in Europe until the late 1700s. They faced skepticism due to unfamiliarity and cultural resistance. However, crop failures, particularly in Eastern France around 1770, spotlighted the potato as a valuable food during scarcity. A farming competition focusing on alternative crops drew attention to its potential. Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, a French chemist and advocate, aggressively promoted potatoes through public demonstrations and tastings. As grain prices soared, Parmentier’s efforts swiftly popularized potatoes across France and eventually Europe.

The widespread adoption of potatoes significantly influenced European populations and economies. Historian William H. McNeill credited the crop with supporting rapid population growth between the 17th and 20th centuries. For instance, Ireland’s population surged from 1.5 million in the 1600s to over 8.5 million after two centuries relying heavily on potatoes. Nutrition from potatoes helped sustain growing urban and rural populations, facilitating Europe’s colonial expansion and industrialization.

Despite their benefits, the reliance on a narrow range of potato varieties introduced vulnerabilities. The European potato monoculture, established from the single S. tuberosum strain cloned from Andean ancestors, increased susceptibility to pests and diseases. The infamous potato blight in the 19th century devastated crops across Europe, especially in Ireland, contributing to famine and mass migration. Similarly, the potato beetle became a major pest in the United States, feeding on vast monoculture fields without resistance.

These challenges provoked advances in agricultural science, prompting genetic improvements and the rise of pesticide and fertilizer industries. Modern farming continues to address the risks of monoculture by developing genetically modified cultivars and integrated pest management strategies. The potato remains a central food crop worldwide, deeply intertwined with history, population dynamics, and agricultural innovation.

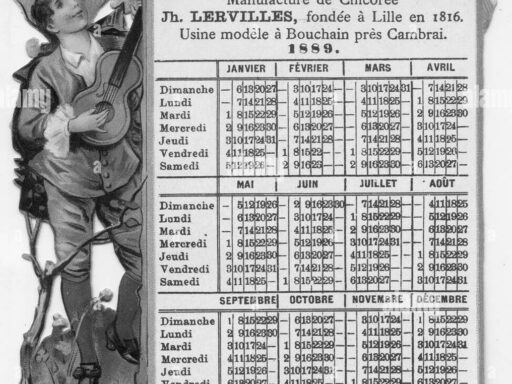

| Timeline | Event | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| ~10,000 BCE | Earliest potato strains in southern Chile | Origin of wild potato types |

| 2,000 BCE | Domestication by Andean peoples | Foundation of cultivated potato varieties |

| 1532 | Spanish contact and introduction to Europe | Start of global spread |

| 1770s | Parmentier’s promotion in Europe | Widespread European acceptance |

| 19th-Century | Potato blight and monoculture crisis | Spawned agricultural innovations |

- Potatoes originated in the Andes of South America over 4,000 years ago.

- Andean farmers used seed-based cultivation, creating vast genetic diversity.

- Europeans encountered the potato in the 16th century with Spanish explorers.

- Potatoes gained prominence in Europe only in the late 1700s, helped by advocates like Parmentier.

- The crop supported population growth but monoculture increased disease risks.

- Modern agriculture continues to innovate to sustain potato production worldwide.

The History of Potatoes: From Andean Roots to Global Tables

The potato, beloved by millions today, started its journey somewhere quite unexpected—in the high Andes of South America. This humble tuber, which now spruces up dinners worldwide, has a rich story that stretches back thousands of years. So, where did potatoes first grow, and how did they spread their charm globally? Let’s dig in.

First, a quick fact to tuck away: over 4,000 varieties of potatoes have been historically cultivated in Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, and Chile. Imagine the flavor and shape diversity hidden in those mountains!

Andean Beginnings: The Birthplace of Potatoes

Potatoes originated in the Andes, where ancient peoples discovered their potential long before Europe ever set eyes on them. Archaeologists have found evidence of potato strains dating back as far as 10,000 BCE in southern Chile. That’s not just old—it’s prehistoric!

By around 2,000 BCE, the Andean peoples had completely domesticated potatoes. This means they weren’t just wild snacks anymore; humans began cultivating them systematically. A neat trick the early farmers used was planting potatoes from seeds derived from flowers, not just potato slices—quite the genetic experiment! This created massive variety, allowing potatoes to adapt to different micro-climates throughout the Andes.

The Potato’s Great Voyage: From Americas to Europe

How did this Andean favorite end up on European tables? Enter the Columbian Exchange, a huge, transformative swap of plants, animals, and ideas triggered by Christopher Columbus’s voyage across the Atlantic.

Francisco Pizarro and his crew, exploring Peru in the 1530s, noticed local people consuming small round tubers. Curious and possibly hungry, they sampled these early potatoes. Back in Europe, the Spanish eventually introduced the Solanum tuberosum strain to the continent through their holdings like the Canary Islands. Early on, potatoes were just an oddity, tucked away in kitchen gardens.

Why Did Europe Take So Long to Love Potatoes?

It might surprise you, but potatoes weren’t an immediate hit. For centuries, Europeans favored grains over tubers. Potatoes stayed a relatively minor food until the late 1700s when a crop failure in Eastern France set the stage for their rise.

This crisis inspired a farming competition called “Plants that Could in Times of Scarcity be Substituted for Regular Food to Nourish Man.” Unsurprisingly, most participants pitched potatoes. Antoine-Agustin Parmentier, a French chemist and fierce potato advocate, emerged victorious. He campaigned tirelessly, organizing clever potato publicity stunts. For example, he had royal guards stand watch over potatoes grown in Parisian fields, making the tuber seem valuable and exclusive, tricking people into trying it.

Simultaneously, price hikes in wheat made the potato an attractive alternative. Parmentier’s efforts helped the humble spud journey from suspicion to staple in households across Europe.

Potato’s Impact: Feeding Nations, Fueling Growth

Potato cultivation coincided with significant population growth in Europe. Historian William H. McNeill credits the tuber for “feeding rapidly growing populations, permit[ting] a handful of European nations to assert dominion over most of the world between 1750 and 1950.” For example, Ireland’s population soared from about 1.5 million in the 1600s to 8.5 million during two centuries dominated by potato-eating. That’s a remarkable jump fueled by starch!

When Monoculture Goes Wrong: The Potato Blight and Beyond

However, the spread of a single cloned potato strain across Europe had a hidden cost. This monoculture set the stage for disaster. The potato blight that struck in the 19th century spread rapidly because it didn’t have to adapt to different potato breeds. It found a banquet in monotonous potato fields, leading to the Great Irish Famine.

Similarly, the potato beetle in the United States thrived on the widespread planting of one tasty potato strain, causing massive pest problems. These agricultural challenges pushed scientists and farmers to develop genetic modifications and led to a boom in pesticide and fertilizer industries.

Potato Trivia and Practical Tips

- Potatoes can be grown from seeds (true seeds) or from potato pieces. Andean farmers mostly used seeds, resulting in great variety. Modern farmers prefer potato pieces for uniform crops.

- Potatoes require relatively cool climates and certain soil types, which historically limited their spread before modern farming techniques.

- Beyond food, potatoes have impacted culture, wars, and economies—an unsung hero in many senses.

Wrapping Up: More Than Just a Side Dish

The potato’s journey from wild Andean tuber to global superfood is a fascinating tale of innovation, adaptation, and survival. From its genetic variety thanks to ancient seed farming practices to scientific efforts that rescued it from monoculture threats, the potato is far more than comfort food. It’s a symbol of how a single crop can shape societies, economies, and even history itself.

Next time you chow down on fries or mashed potatoes, remember: you’re biting into 10,000 years of human ingenuity and adventure. Now, isn’t that a tasty history lesson worth savoring?

Where did potatoes originally start growing?

Potatoes originated in the Andes region of South America. Ancient peoples in Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, and Chile cultivated them thousands of years ago. Archaeological evidence dates some strains back to 10,000 BCE in southern Chile.

How did potatoes spread from the Andes to the rest of the world?

Potatoes were first encountered by Europeans during expeditions like those of Francisco Pizarro in the 1530s. The Spanish brought one strain, S. tuberosum, to Europe. From there, cultivation spread to other countries including France and the Netherlands.

Why did the potato become popular in Europe only in the late 1700s?

Although introduced earlier, potatoes remained a minor food until crop failures like the one in Eastern France in 1770. This led to competitions promoting alternative foods. Antoine-Agustin Parmentier also campaigned for potatoes, increasing their acceptance during rising grain prices.

What impact did potato cultivation have on European populations?

Potatoes supported rapid population growth between the 17th and 20th centuries. For example, Ireland’s population grew substantially during about 200 years of heavy potato eating. The crop helped sustain expanding populations and economic development.

What were the agricultural risks of introducing a single potato strain to Europe?

The reliance on one cloned potato strain created large monocultures vulnerable to pests and diseases. Potato blight and beetles spread rapidly because they faced no genetic resistance. This contributed to major crop failures and drove advances in genetic modification and pesticide use.