A Jacobite supports the restoration of James II and his Stuart heirs to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland, advocating monarchist and absolutist principles. In contrast, a Jacobin is a member of a radical political club during the French Revolution that championed republicanism, universal male suffrage, and the separation of church and state. These two groups emerge from different historical contexts and represent opposing political ideologies despite some similarities in their underground and populist nature.

Jacobitism began after James II of England and VII of Scotland was deposed in 1689. The movement aimed to restore him and his descendants to power. The name derives from the Latin “Jacobus,” meaning James. Jacobitism was a transnational cause with strong support across the three kingdoms: England, Scotland, and notably Ireland. It often operated as a secret or underground movement. Members engaged in smuggling, clandestine communications, and plotting military uprisings to reinstate the Stuart monarchy.

In Ireland, Jacobitism strongly intertwined with nationalist sentiment. The cause symbolized resistance to English political dominance and became a unifying force for Irish nationalism. This movement went beyond mere loyalty to James II and embodied broader goals of Irish self-determination. Despite its strong cultural and political impact, Jacobitism gradually declined, effectively ending by about 1745 after the failure of the last major Jacobite Rebellion.

Jacobinism emerged during the French Revolution in the late 18th century. The Jacobins formed a political club initially aimed at limiting the powers of the French monarchy. However, radical members such as Maximilien Robespierre pushed the club towards a republican and revolutionary agenda. They advocated for the abolition of monarchy, instituting democratic reforms like universal male suffrage and enforcing secular governance.

The Jacobins also operated through secretive networks, especially in Paris, where political expression was restricted. Like the Jacobites, they maintained underground channels and a strong internal culture to survive repression. Support for Jacobin ideas spread beyond France, significantly influencing political thought in Ireland.

Irish support for the French Revolution was enthusiastic, with Jacobin radicalism inspiring the Irish republican cause. Jacobinism provided a new ideological framework for those who desired Irish independence and republic governance. The republic status of Ireland today can trace ideological roots back to this Jacobin influence.

| Aspect | Jacobites | Jacobins |

|---|---|---|

| Time Period | Late 17th to mid-18th century | Late 18th century |

| Geography | British Isles (England, Scotland, Ireland) | Primarily France, with influence in Ireland |

| Political Goal | Restore James II and Stuart monarchy | Establish a republic |

| Political Ideology | Monarchist, absolutist | Republican, democratic, secular |

| Movement Nature | Underground, clandestine, secret networks | Underground, secretive, popular faction |

| Role in Irish Nationalism | Symbol of resistance to English control, tied to nationalism | Inspired Irish republicanism and independence movements |

While Jacobitism favored hereditary monarchy and traditional hierarchies, Jacobinism sought revolutionary change toward democratic principles. They stand at opposite ends of the political spectrum in their respective eras. Both movements, however, shared a grassroots character and operated partly through secretive, underground means within states hostile to their aims. This made political activism risky but contributed to a sense of shared cause and identity.

The political landscape in the British Isles did not witness a revolution akin to France’s in 1789. Some historians argue the Glorious Revolution of 1688 served as a British counterpart. Nevertheless, sympathy for the French revolutionary cause existed, especially in Ireland and Scotland. After the decline of Jacobitism, many Irish nationalists faced an ideological gap.

This gap was often filled by Jacobinism, which offered a new vision of political opposition that was more aligned with republican ideals rather than the absolutism of the Stuarts. The transition from Jacobitism to Jacobinism in Ireland represented a shift in strategy and ideology but remained rooted in resistance to British rule. Despite their stark ideological differences, the evolution from Jacobitism to Jacobinism reflects a continuous thread of political dissent in British and Irish history.

- Jacobites supported restoring James II and his Stuart lineage; Jacobins supported establishing a republic during the French Revolution.

- Jacobitism was monarchist and absolutist; Jacobinism embraced democratic and secular reforms.

- Both operated through secretive networks but differed in political goals and historical contexts.

- Jacobitism strongly influenced Irish nationalism, symbolizing resistance to English rule.

- Jacobinism inspired later Irish republicanism, contributing to Ireland’s republican status.

What Is the Difference Between a Jacobite and a Jacobin?

If you’ve ever stumbled upon references to Jacobites and Jacobins and scratched your head wondering, “Wait—are they just fancy names for the same thing?”—you’re not alone. The names sound alike, yet they represent utterly different historical movements. So, what’s the difference between a Jacobite and a Jacobin? Simply put, Jacobites supported the return of the Stuart king James II and his descendants to the British throne, while Jacobins were radical revolutionaries in France championing a republican revolution.

Let’s dive deeper. These two groups emerged in distinct eras and contexts. They both stirred political upheaval, but their aims, methods, and ideologies could not be further apart.

The Jacobites: Royalists in the Shadows

The word “Jacobite” traces back to Jacobus, the Latin form of James. It sprang up after the 1688 Glorious Revolution ousted King James II from the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Jacobitism was essentially a royalist cause seeking to restore James II and his heirs to power.

Your mental image of Jacobites might be a secretive band of loyalists plotting in smoke-filled rooms. They functioned largely as an underground political movement. Smuggling, clandestine communications, and covert rebellion attempts were a big part of their strategy. It’s like an 18th-century spy thriller but with less glassware breaking and more intrigue.

Interestingly, Jacobitism grabbed a tight hold in Ireland. The cause merged with Irish nationalism, symbolizing more than a king’s return—it became a rally against English domination. Irish Jacobitism gave nationalism sharper goals and a united front. In Scotland, too, Jacobitism resonated deeply, fostering a sense of political distinctiveness and opposition to the British crown’s control.

But even the steadiest fires burn down eventually. After the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, hopes for restoration fizzled. The movement quickly declined, marking the Jacobite cause as a romantic but doomed chapter of British–Irish history.

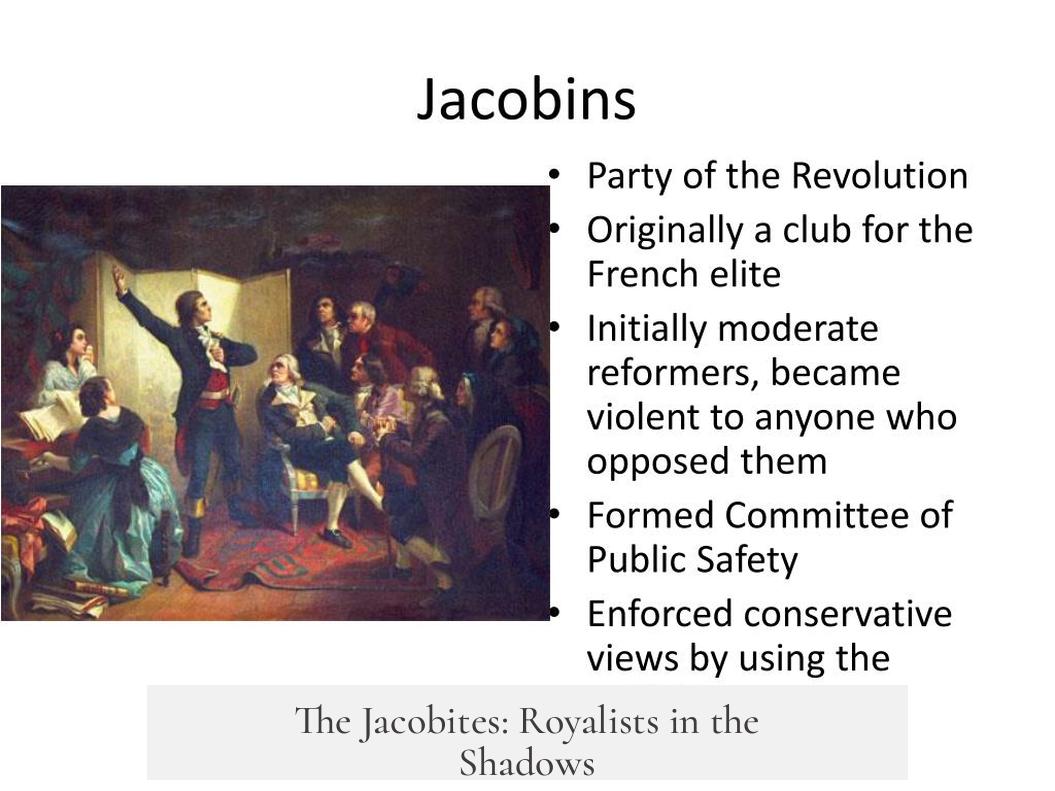

The Jacobins: Revolutionaries Shaking Paris

Flip over to France about a century later, and the Jacobin Club dominates the political stage during the French Revolution. Unlike Jacobites who aimed to restore monarchy, Jacobins initially called for *reform*, then quickly ramped up to radical Republicanism under the leadership of the infamous Robespierre.

Their agenda was bold: universal male suffrage, abolition of the monarchy, and a sharp division of church and state. Talk about a political rollercoaster—Jacobins went from moderates to some of the revolution’s most feared radicals.

Much like Jacobites, Jacobins carved out secretive networks, especially in Paris. Their meetings and internal culture resembled a shadowy political club focused on overthrowing the old order. These underground setups grew popular because the existing system resisted widespread citizen participation.

The French Revolution’s fervor spilled over into Ireland, where radical ideas inspired a republican mindset. Jacobinism fueled Irish republicanism’s dream, eventually shaping Ireland into the republic it is today—a legacy far removed from the royalist hopes of the Jacobites.

Political Opposites on Many Levels

So, Jacobites and Jacobins—are they two peas in a pod or oil and water? Well, they share some traits as secretive movements but differ wildly in goals and ideologies.

| Aspect | Jacobites | Jacobins |

|---|---|---|

| Time & Place | Late 17th to mid-18th century Britain & Ireland | Late 18th century Revolutionary France |

| Main Goal | Restore James II and Stuart monarchy | Establish Republic; abolish monarchy |

| Political Ideology | Absolutist monarchy | Republicanism, universal male suffrage, secularism |

| Movement Nature | Underground, secretive; royalist | Radical, populist, secret clubs |

| Irish Connection | Attached to Irish nationalism; anti-English rule | Inspired Irish republicanism and independence |

The Jacobites cling to the past with their absolutist monarchy dreams, while Jacobins sprint ahead to ideas of democracy and individual rights. It’s like comparing a vintage car to a turbocharged electric car—both moving politics but at very different speeds and directions.

From Jacobitism to Jacobinism: Irish Political Evolution

One fascinating twist is the Irish political transition from Jacobitism to Jacobinism. After the Jacobite movement collapsed post-1745, Irish nationalism faced a void in its oppositional energy. Jacobinism, with its revolutionary zeal and republican ideals, stepped in to fill the gap quite naturally.

You might think switching from supporting an absolutist king to radical republicans would cause whiplash, but many Irish activists found the move seamless. Both movements symbolized resistance against British domination. Radical republicanism wasn’t just politically attractive; it represented a new pathway for Irish identity and freedom.

Think about it: the same underground style of political activity fit both movements—secret meetings, coded letters, and networks of support. The tactics stayed familiar; only the flags changed.

So, Is It Just All a Name Game?

Not quite. The connection is mostly linguistic and tactical rather than ideological. Jacobites wanted a king back on the throne, Jacobins wanted to tear down monarchies altogether. Their shadows overlap more in Ireland’s political landscape than in their actual beliefs.

Why Should You Care?

Understanding the difference between Jacobites and Jacobins isn’t just academic trivia. Their stories illuminate the complex evolution of political ideas, resistance, and identity in Britain and Ireland. From secret loyalties to revolutionary fervor, these historical threads weave the tapestry of modern democracy and nationalism.

Next time you hear someone casually drop “Jacobite” or “Jacobin” at a party or in a history book, you’ll wow them with your grasp of two very different revolts. Oh, and if you want to impress even further, mention how Ireland’s nationalist journey bridges these moments—from royalist rebellion to republican revolution.

History isn’t just names and dates. It’s ideas clashing, funding smuggled, flags raised, and ordinary people changing entire nations.

What key political goals distinguished Jacobites from Jacobins?

Jacobites sought the restoration of James II and his absolutist Stuart line. Jacobins pushed for Republicanism, universal male suffrage, and separation of church and state. Their aims placed them at opposite ends of the political spectrum.

How were Jacobitism and Jacobinism similar in their methods?

Both operated as underground movements with secret communication and networks. They involved clandestine activities and gained popular support in Ireland, maintaining covert political cultures under restrictive regimes.

Why did Irish nationalism shift from Jacobitism to Jacobinism?

The fall of Jacobitism weakened Irish political nationalism. Many Irish supporters then embraced Jacobinism, which offered a new oppositional cause aligned with Republican ideals opposing British rule.

Did the British Isles experience a revolution like France, influencing Jacobinism there?

No true revolution occurred in the British Isles as in France, though the 1688 events were seen as similar. Nonetheless, Jacobin ideals found sympathy, especially in Ireland and Scotland, influencing local political movements.

How did Jacobitism relate to Irish nationalism?

Jacobitism closely linked to Irish nationalism, symbolizing resistance to English domination. It unified political groups and shaped nationalist goals before its decline around 1745.