After World War II, the average German soldier experienced diverse fates ranging from imprisonment, joining foreign military forces, to reintegration challenges within a shattered Germany. The outcomes varied greatly depending on which Allied power captured them and their military background.

Most enlisted German soldiers in the Wehrmacht became prisoners of war (POWs). They were held in camps established across Germany and Allied countries. Conditions in these camps varied significantly. The Western Allies—particularly the Americans and British—typically detained soldiers only for a few months. Their goal was to identify who were hardcore Nazis and who were merely followers (Mitläufer). Due to pressure from the U.S., Britain and France began releasing POWs relatively quickly after Germany’s surrender. Many former soldiers were thus able to return home within weeks or months. An example includes soldiers retreating from the Eastern Front who surrendered to Western forces and were soon freed.

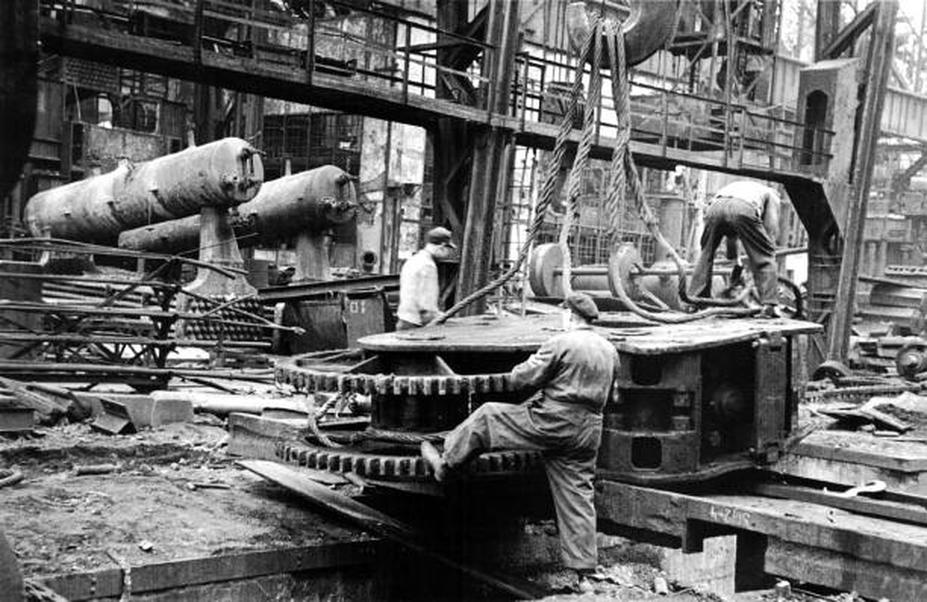

In contrast, the Soviet Union detained German POWs for much longer periods. Many were transported east into camps similar to the GULAG system, called GUPVI. There, prisoners often endured harsh conditions for up to a decade, facing forced labor and slow repatriation. In 1955, the USSR notably released about 10,000 remaining prisoners. This difference in captivity length underscored the tension between East and West during the early Cold War.

A considerable number of German soldiers, especially combat veterans, did not return to Germany immediately. Instead, many joined the French Foreign Legion. The Legion sought experienced troops to fight colonial insurgencies, notably in French Indochina. Despite official bans on former Waffen SS members, the French frequently overlooked these restrictions to recruit skilled Germans willing to continue fighting communism. Veterans often concealed their identities, enlisting under fake nationalities such as Polish, Dutch, or Czech. At one point, as many as 60% of the Legion’s soldiers were German.

Joining the Foreign Legion offered displaced German soldiers a way out of a devastated homeland and a chance to avoid prosecution for wartime acts. Their military skills were highly valued during brutal colonial conflicts, and the Legion sustained heavy casualties without similar concern for non-French troops.

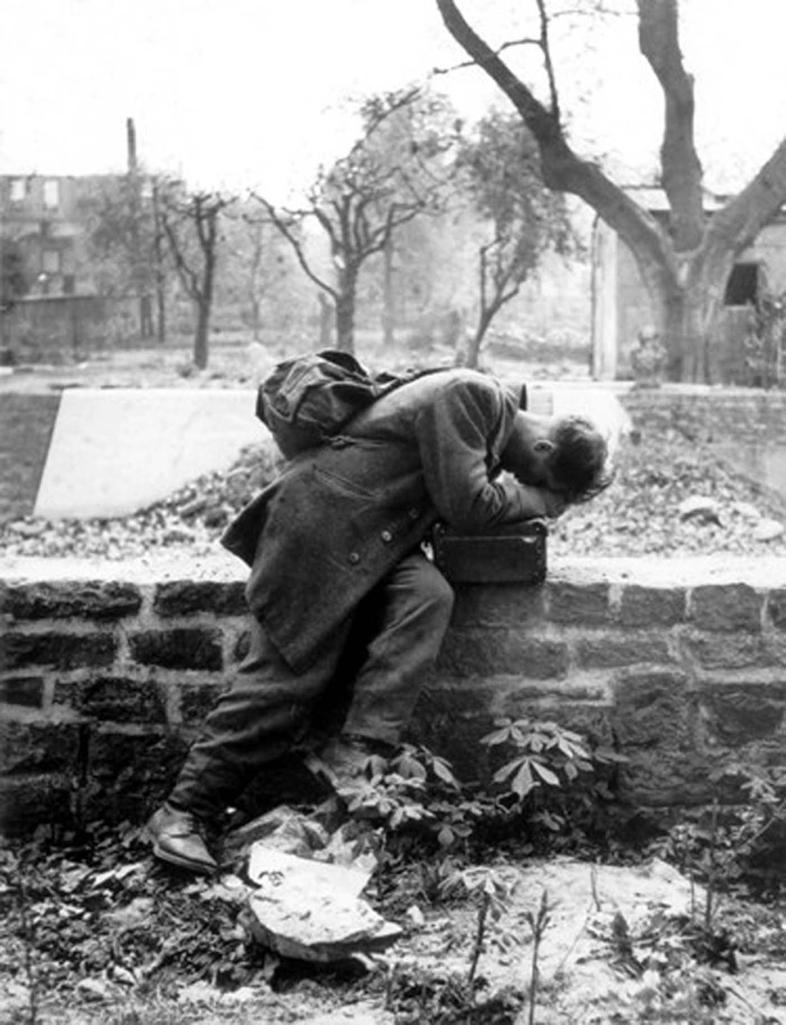

The majority of soldiers who returned to Germany faced difficult reintegration. The country was politically unstable and physically ruined. Many lived under suspicion, often accused of war crimes or Nazi collaboration. The process of resuming civilian life was slow. Some spent years coping with accusations before being cleared. The broader society grappled with the legacy of the war while trying to rebuild their lives. Former soldiers endured social and economic hardship during this transition.

The experience of German soldiers after 1945 is complex and multi-faceted. Some returned quickly from Allied captivity. Others suffered prolonged imprisonment, especially in the East. A significant minority fought with foreign military units like the French Foreign Legion. Across these paths, many lived with the long shadow of suspicion and upheaval.

| Postwar Fate | Description |

|---|---|

| Western POW Camps | Detained briefly, months-long, followed by release after Nazi allegiance assessment |

| Soviet GUPVI Camps | Harsh conditions, forced labor, imprisonment lasting up to 10 years or more |

| French Foreign Legion | Many enlisted despite restrictions, fought in colonial conflicts, concealed identities |

| Reintegration in Germany | Political instability, social suspicion, delayed return to normal life, accusations of war crimes |

For those seeking deeper insight, academic works provide detailed analyses. Recommended resources include From Incarceration to Repatriation by Susan Grunewald, Homecomings by Frank Biess, and War Stories by Robert Moeller. These studies explore incarceration, repatriation, and societal reintegration of German soldiers. Historians like Ian Kershaw and Richard Bessel have also produced extensive works on Germany’s immediate postwar period.

- Most enlisted German soldiers became POWs held by Allies, with Western forces releasing many within months.

- Soviet captivity was often long and harsh, sometimes lasting a decade in forced labor camps.

- Thousands joined the French Foreign Legion, fighting in colonial wars and avoiding legal repercussions.

- Reintegration was difficult amid political chaos, with suspicion and accusations common.

- Scholarly books provide detailed accounts of these diverse soldier experiences after WWII.

What Happened to the Average German Soldier Following the Conclusion of WW2?

After World War II, the fate of the average German soldier was a complicated mix of imprisonment, escape, suspicion, and surprising second acts—most notably, their frequent enlistment in the French Foreign Legion. The war’s end didn’t simply mean going home. For many Wehrmacht members, it meant captivity, exile, or a new kind of soldiering under foreign banners.

Let’s unravel what life looked like for these men, who were suddenly left without a country, an army, or a clear role in a dramatically transformed world.

A Surplus of Soldiers, a Ruined Homeland, and the Call of the French Foreign Legion

Imagine you’re a German soldier in 1945: your country is shattered, divided between four occupying powers, and your military no longer exists. For many such men, one of the most unexpected chapters began when they signed up for the French Foreign Legion.

Why the Legion? Well, the French desperately needed soldiers to fight their colonial wars, particularly in French Indochina. Meanwhile, German veterans, many of them hardened fighters, sought to escape not just their destroyed homeland but also potential trials for war crimes or simply the trauma of defeat.

Officially, the Legion barred Waffen-SS veterans, but in practice, this rule was largely ignored. The French were pragmatic, almost desperate for manpower, and at times encouraged these men to assume new identities — claiming Polish, Dutch, or Danish nationality to slip past any hurdles.

In fact, at one point, up to 60% of the French Foreign Legion was German. Their combat experience, brutal as it was, proved invaluable in colonial conflicts where the French paid little heed to casualty numbers among non-French troops.

The Legion lost 300 officers and 11,000 men in these attritional wars, but French attitudes were largely indifferent since these were mostly ‘expendable’ foreign soldiers.

This blend of necessity and opportunity created an almost hidden postwar narrative: German veterans continuing their martial careers far from home, often to fight against communists — a cause many still held dear.

From Wehrmacht to POW Camps: The Varied Paths of Captivity

Of course, not every soldier charged off to a new battle. For the majority — typically enlisted Wehrmacht men, not SS members — capture by Allied forces was the immediate reality.

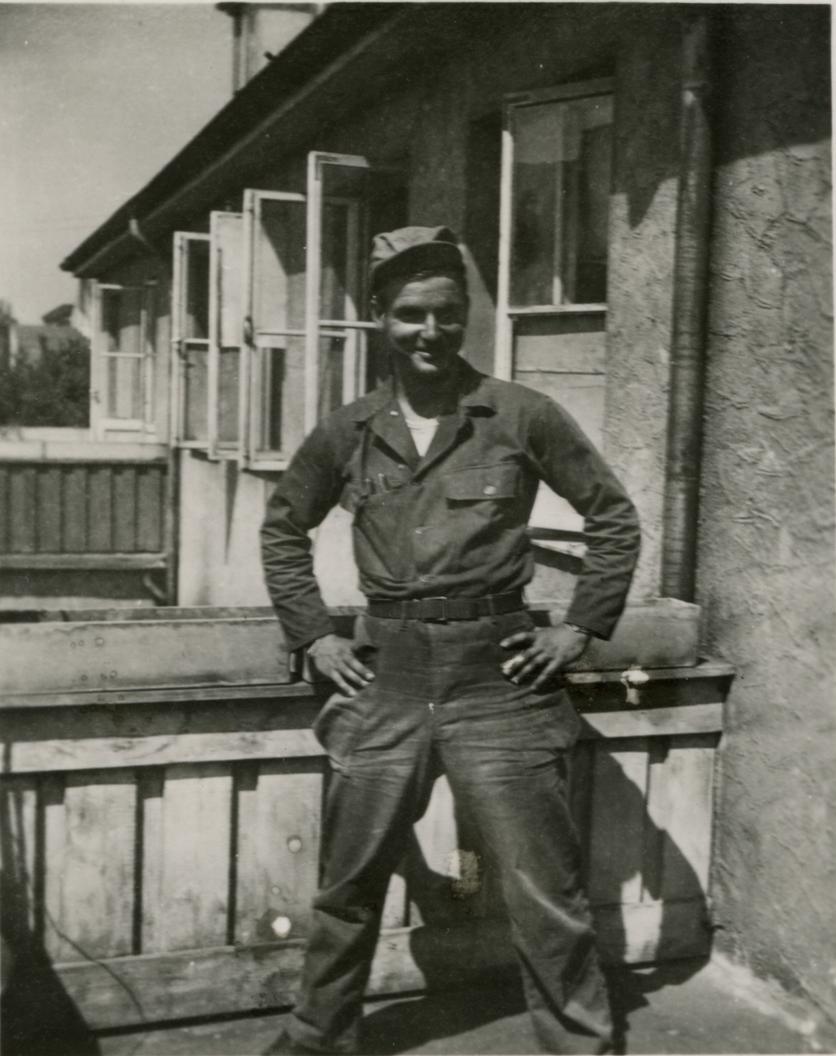

The POW experience varied dramatically depending on which side held them. Western Allies (Britain, U.S., France) generally interned soldiers for only a few months after the surrender. They differentiated between hardline Nazis and ‘Mitläufer’ — those who were followers, not ideologues — and began releases swiftly. Some German prisoners, like the blog author’s grandfather, were released mere weeks after capitulation and made their own way home on foot.

The Soviet Union operated a very different system. They transported millions eastward to labor camps known as GUPVI, camps akin to the infamous GULAG but specifically for POWs. Release there could be delayed a decade or more, with some prisoners only freed as late as 1955.

The longest detentions created generations of lost time, delayed family reunions, and prolonged the soldiers’ limbo beyond the war’s official end.

So you had two starkly different postwar realities for the average soldier based on their captor, adding layers of uncertainty and hardship, especially under Soviet captivity.

Reintegration Into a Fractured German Society

When they finally returned — if they survived captivity — German soldiers faced a country in turmoil. The immense political and social upheaval meant reintegration was rarely smooth.

Many former soldiers found themselves subject to suspicion, accused unfairly or not of war crimes. The postwar years in Germany were marked by a haze of accusations, legal proceedings, and social unrest.

A striking example comes from the book Fatherland, about a German-American who researched his Nazi grandfather’s story. It took that man about ten years to rebuild his life postwar, partly because of local political chaos and victimization by opportunists amid the power vacuum left by the conflict.

Most average soldiers did manage to reintegrate eventually, but it often took several years or even a decade, especially if they endured extended captivity in the Soviet Union. Years of suspicion and political instability hung over their return, coloring their civilian lives.

Academic Insights: A Closer Look at the Postwar Soldier’s Journey

If you’re itching to dig deeper into what happened to these men, several academic sources provide rich details and analysis. Notable titles include:

- Susan Grunewald’s From Incarceration to Repatriation, which examines the process of release and homecoming for POWs.

- Frank Biess’ Homecomings, offering a profound look at the psychological and social challenges veterans faced returning to civilian life.

- Robert Moeller’s War Stories, discussing personal narratives and the memory culture of German soldiers after 1945.

Big-name historians like Ian Kershaw and Richard Bessel have also synthesized broad postwar experiences, painting a picture of defeat, suspicion, and eventual recovery that mirrors the fate of countless soldiers.

So What Does This Mean, Really?

The story of the average German WWII soldier after the war is not a tidy one. It’s charged with irony, hardship, and unexpected new beginnings.

- Many soldiers chose to keep fighting—not for Germany, but under the Legion’s flag in colonial wars, often to avoid prosecution or start anew.

- Most endured captivity, with conditions and durations depending heavily on who controlled their fate.

- The homecoming was fraught — suspicion lingered, political turmoil roiled, and trust was often hard-won.

- For some, decades passed between fighting in the war and building a peaceful civilian life.

Imagine the emotional weight carried by a man who fought for years, was captured, perhaps imprisoned for a decade, and returns to a homeland no longer his own. In many ways, their postwar journey was just as challenging—and transformative—as the war itself.

Reflective Questions

- How would you cope with a decade of imprisonment far from home, and then return to a society suspicious of you?

- What does it say about the nature of loyalty and identity that so many former German soldiers fought on under foreign banners?

- What lessons about reintegration and reconciliation can modern societies learn from postwar Germany?

Ultimately, the fate of these soldiers teaches us about resilience and complex identities shaped by the pressures of history, politics, and survival.

Final Thoughts

The aftershocks of World War II rippled deeply into the lives of millions of soldiers who suddenly found themselves out of place, out of favor, and often out of hope. The story of the average German soldier after 1945 is layered with loss and reinvention—whether through captivity, exile, fresh enlistment, or painstaking return to civilian existence.

While many settled quietly back into civilian roles, others carved unexpected paths on foreign battlefields. This split fate is a powerful reminder that war’s end is rarely neat and often marks the beginning of equally complex journeys.

So next time you think of a WWII soldier, remember: for many, the war officially ended in 1945—but their personal battles continued for years, sometimes decades, in far-flung places and uncertain homes.