Chariot racing, once a grand spectacle of the ancient Roman world, faded gradually due to economic, political, and military changes across the Roman Empire. The sport declined in the West by the 5th century, persisted longer in the East, but ultimately ceased after the 13th century in Constantinople.

The decline begins with the Western Roman Empire. Chariot races required vast expense to organize and maintain, including the upkeep of large arenas known as circuses or hippodromes. As the Empire’s revenues dropped, wealthy patrons could no longer support the sport. The 5th century accelerated the decline: political instability weakened central authority, and major landowners faced financial losses. These factors made maintaining the expensive venues less viable across the Western provinces.

Italy experienced an exception during this decline. The Circus Maximus in Rome remained operational through the rule of Odoacer and the Ostrogoths. Consuls still sponsored games, and notable figures like Theoderic the Great hosted chariot races during visits. This continuation reflects Rome’s lingering political importance and cultural resilience, but it was temporary.

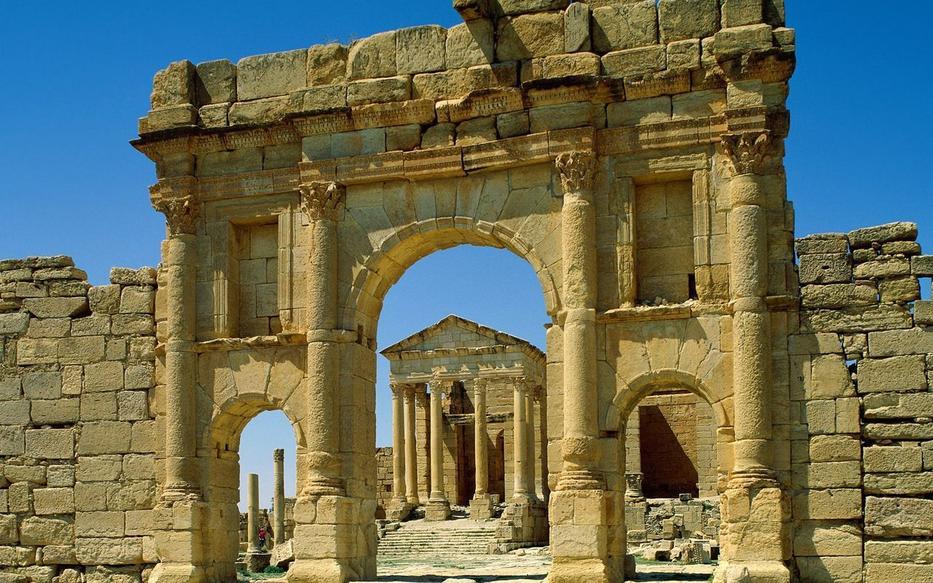

The Gothic Wars (535–554 CE) financially and demographically devastated Italy. This destruction rendered chariot racing impractical even in Rome. The final recorded race occurred in 549 CE under Totila, following his siege of the city. After these conflicts, circuses lost their purpose as secular authorities collapsed and the wealth that sustained games disappeared. Consequently, circuses fell into ruin. Their stones were scavenged and repurposed as spolia for other construction projects.

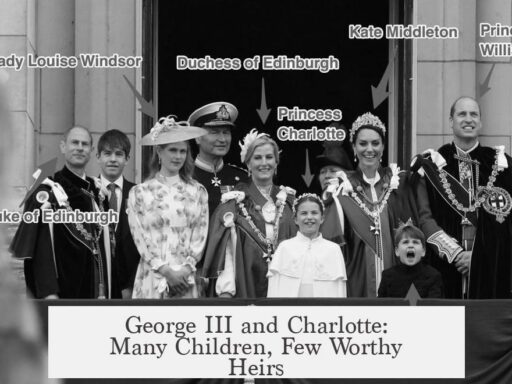

| Region | Chariot Racing Status | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Western Roman Empire | Declined by 5th century, ended mid-6th century | Economic decline, weakened political control, Gothic Wars |

| Italy (Rome) | Continued until mid-6th century | Persistence of aristocratic sponsorship, later destruction by war |

| Eastern Roman Empire | Thrived until 7th century, survived longest in Constantinople | Stable governance, wealth, later Arab conquests reduced resources |

| Constantinople | Survived until 13th century | Imperial patronage, sacking in 1204, decline post 4th Crusade |

The Eastern Roman Empire, later known as the Byzantine Empire, initially maintained chariot racing well beyond the West’s decline. The 5th and 6th centuries found Constantinople and other Eastern cities maintaining wealthy landowners, senators, and emperors who could fund these grand events. A central government provided stability and funds, keeping hippodromes operating.

However, the 7th century introduced transformative challenges. Arab conquests seized Egypt, Syria, and North Africa, regions crucial for revenue. These military losses drastically reduced Imperial income. Many cities beyond Constantinople suffered decline or disappeared. Wealth and population shrinkage meant many formerly vibrant venues ceased operation.

Constantinople remained an outlier. Its defensible location and status as the imperial seat allowed continued chariot celebrations, financed increasingly by the imperial family rather than wealthy private sponsors. Teams such as the Blues and Greens stayed active but under tighter imperial control. The games became intertwined with imperial ceremonies and propaganda, sometimes manipulated to glorify the reigning emperor.

This arrangement persisted until the city suffered a severe blow in 1204 during the 4th Crusade. Crusaders diverted from their mission sacked Constantinople, looting and destroying many of its treasures. The Latin Empire replaced the Byzantine administration, introducing inefficient feudal governance. The new regime failed to maintain the infrastructure and cultural institutions properly, including the Hippodrome.

The Hippodrome, the last major ancient circus, fell into ruin during this period. When the Byzantine Empire regained the city in 1261, economic decline prevented restoration efforts. After this point, chariot racing ceased altogether.

Chariot racing’s end marks the broader transition from classical antiquity to the medieval world. Its decline reflects shifting economic conditions, political structures, military upheavals, and evolving cultural priorities.

- The Western Roman Empire’s chariot racing faded by the mid-6th century due to economic and political crises.

- Italy’s Circus Maximus operated during Ostrogothic rule but ended after the destructive Gothic Wars.

- The Byzantine Empire maintained racing longer, particularly in Constantinople, adapting the sport under Imperial patronage.

- Arab conquests in the 7th century diminished Eastern revenues, reducing chariot racing outside Constantinople.

- The 4th Crusade’s sack of Constantinople in 1204 and subsequent decline ended the last surviving chariot races.

What happened to chariot racing? A deep dive into the fall of ancient motorsport

Chariot racing, once the pulsating heart of Roman and Byzantine public life, slowly vanished from the tracks due to economic troubles, political upheaval, and wars. It didn’t crash overnight; instead, it drifted off as centuries passed and empires waned.

Why did something so wildly popular in antiquity just… stop? Let’s pull back the curtains on this ancient spectacle.

The decline in the Western Roman Empire: When the thrill lost its fuel

Chariot races were grand events but also incredibly costly. They demanded maintenance of vast hippodromes, expensive teams of horses, and skilled drivers. In the Western Roman Empire during the 5th Century, the money started drying up. Revenues were tight, and wealthy landowners—the traditional sponsors—grew less wealthy.

Imagine trying to keep a deluxe, ancient sports stadium open without fans buying tickets or sponsors showing up with fat purses. The Circus Maximus and other venues gradually became financial burdens.

- Central authority weakened, making organizing large games harder.

- Landowners reduced their patronage as wealth shrank.

- Hippodromes across the west became impractical to maintain.

Still, Italy clung to chariot racing a bit longer. Rome’s Circus Maximus, for example, saw races sponsored by consuls even under Ostrogothic rule. Theoderic the Great himself sponsored a race—proof that chariot racing still had some juice left.

But all good things bow to war. The devastating Gothic Wars sapped Italy’s finances and population. In 549 AD, Totila is recorded holding the last known chariot race in the Circus Maximus after seizing Rome. After this, the games simply didn’t make sense anymore.

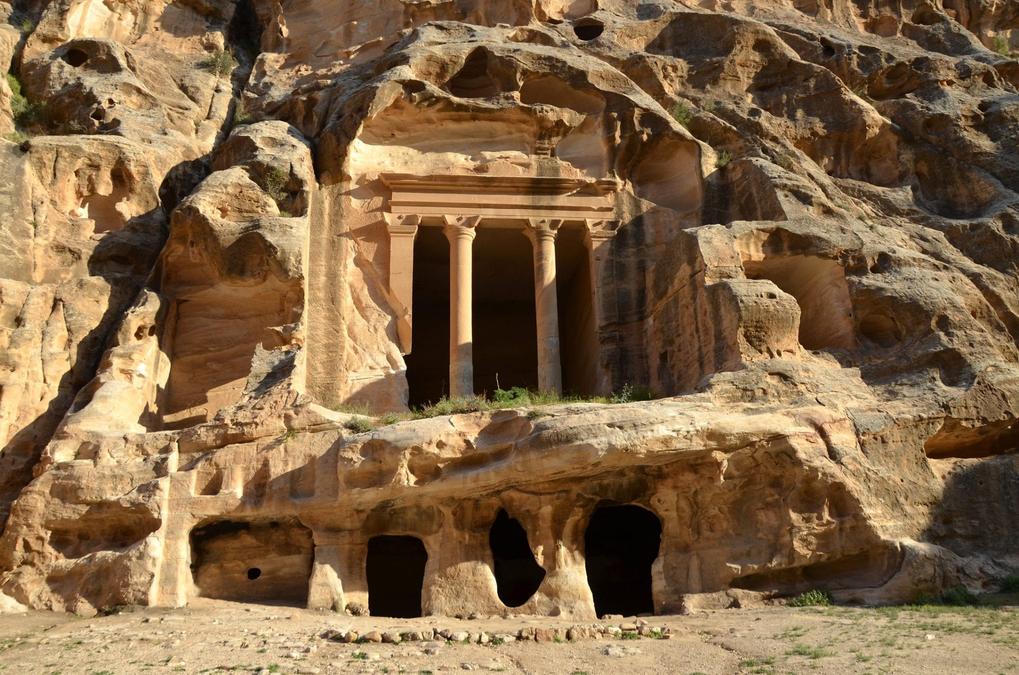

With no use for the vast circuses and no funds to maintain them, the structures fell into ruin. Stones from these venues went on to have new life as building materials—spolia recycled for survival, making chariot racing an archaeological memory.

The Eastern Roman Empire: Chariot racing’s final lap

While the West struggled, the Eastern Roman Empire—better known to history buffs as the Byzantine Empire—kept the chariot wheels spinning a little longer. The East avoided many 5th Century crises that hit the West hard. There were still rich patrons, a functioning administration, and a still-thriving capital: Constantinople.

For a time, chariot racing prospered there, with teams like the Blues and Greens fiercely competing in the Hippodrome, still a monumental stadium. Races went beyond mere sport; leaders used them for political capital and public influence.

That all shifted in the 7th Century, when the Muslim Arab conquests struck. The Byzantine Empire lost key provinces—Egypt, Syria, and North Africa—causing revenue losses and city populations to shrink or vanish. Many Eastern provincial cities stopped hosting races as their hippodromes fell silent.

But Constantinople held fast, thanks to its prime location and fortifications. Chariot racing didn’t die — it transformed. Imperial families took over funding races. The once-independent teams became closely tied to the emperor. Imagine it as the ultimate brand sponsorship: the emperor’s image riding shotgun.

Given these circumstances, some scholars compare late Byzantine chariot racing to an ornate imperial ceremony—a state spectacle used to boost the regime and manipulate public opinion. The races even may have been rigged. Sports, ancient-style political theater!

The crushing blow: Fourth Crusade’s siege and the end of the races

All this endurance came to a stumbling halt in 1204. The Fourth Crusade didn’t reach the Holy Land as intended. Instead, Crusaders sacked Constantinople. They pillaged the city like a Black Friday sale and set fires that raged uncontrolled.

The Latin Empire that replaced Byzantine rule was a shadow of the old empire. Its feudal governance lacked the centralized bureaucracy needed to maintain city institutions. Revenues collapsed, and with them went the ability to sponsor chariot games.

The Hippodrome—the last great circus standing from ancient times—fell into disrepair. When the Byzantines finally recaptured Constantinople in 1261, their resources were stretched thin. Restoring the Hippodrome wasn’t a priority, sealing the fate of chariot racing.

Why hasn’t chariot racing survived?

Many sports fade when popularity ebbs, but chariot racing’s extinction was tied tightly to economics and politics. Holding extravagant races requires money, power, and social stability.

As both Roman empires fragmented and funds vanished, chariot racing went from popular entertainment to an expensive relic. War and upheaval finished what slow decline began.

Also, changing tastes played a role. As Christianity became dominant, the bloody, dangerous spectacle of chariot racing clashed with new moral attitudes. The Church sometimes opposed such pagan-associated games.

No rebirth in a new form ever happened either. Unlike, say, gladiatorial combat evolving into more regulated contests, chariot racing simply lost its place.

Lessons from chariot racing’s fall

This ancient sport teaches us that no matter how grand an entertainment is, sustainability depends on stable economic and political foundations.

Host cities need strong leadership and wealth to keep such spectacles alive. Without that, even the most thrilling races sputter out like a broken chariot.

It also reminds us how closely sports and politics often intertwine. Emperors used chariot races as propaganda tools centuries before politicians mastered social media.

So next time you watch a race—even NASCAR or Formula 1—think about ancient Rome’s charioteers, who raced for glory, empire, and survival. Their sport didn’t vanish suddenly but ran a long, winding course that ended as the world changed around them.

Chariot racing: the first motorsport, gone from the track but never from history.