The difference between a peasant, a serf, a smallholder, and a tenant farmer lies chiefly in their legal status, land ownership, obligations, and degree of freedom within medieval agrarian society. Each represents a distinct social category linked to the ways land was worked and controlled in Europe, especially after the Norman Conquest and around the time of the Domesday Book in 1086.

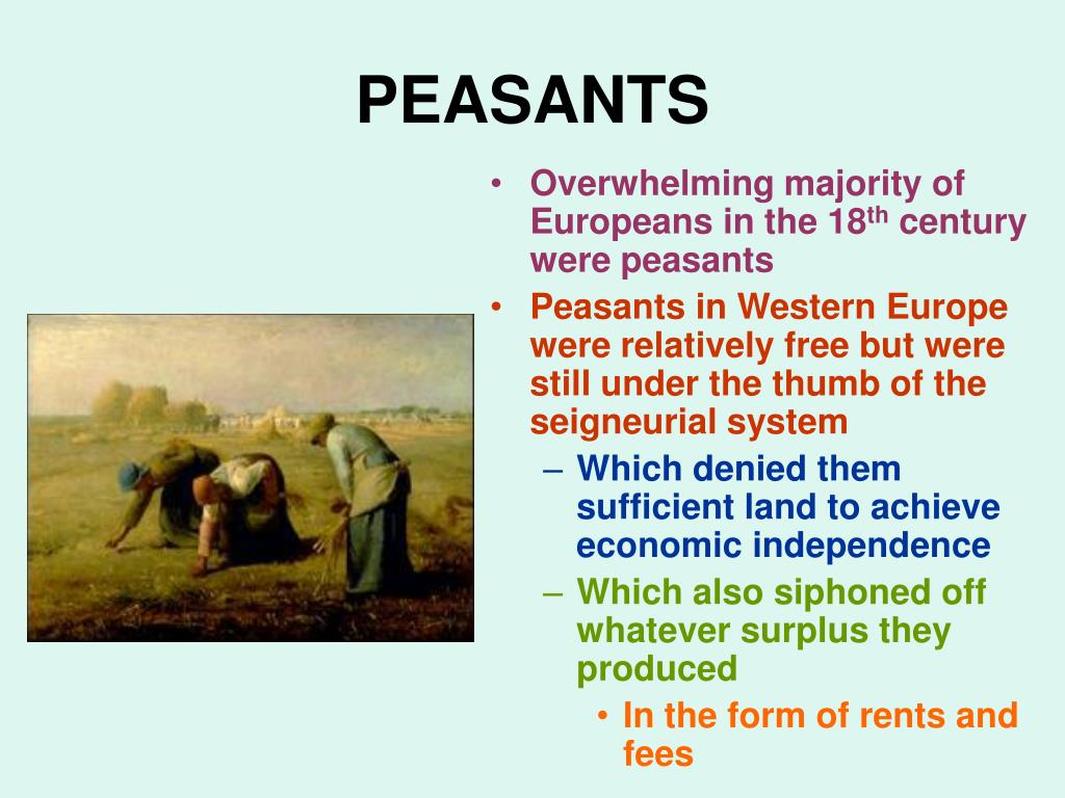

A peasant is a general term for anyone engaged in agriculture. This group encompasses a broad range of rural workers living in agrarian communities. The word originates from the Latin pagus, meaning countryside. Peasants work the land, but their exact status can vary widely. Some may own land, others may rent or be bound by various social rules. Essentially, the peasant class forms the base of the rural workforce.

A tenant farmer is a type of peasant who rents land rather than owning it. Tenant farmers cultivate land leased from landlords or nobility. They differ from free peasants who may own land outright or hold land directly from the king as tenants-in-chief. While tenant farmers must pay rent—often via labor service, such as working one or two days a week on their lord’s land—they retain certain freedoms compared to serfs. They are not permanently bound to the land but are obligated by contracts or rental agreements that define their tenure. Tenant farmers dominated the agrarian system at the Domesday survey, representing most of the rural population.

- Rents varied but typically involved labor.

- Tenure contracts ranged from long-term to flexible.

- Some tenant farmers worked as wage laborers or contracted multi-generational tenants.

A smallholder represents a lower tier within the tenant farming class. Smallholders usually cultivated smaller plots, about 5 to 15 acres, compared to villeins—typical larger tenant farmers—who held around 30 acres. Smallholders tended to own or lease a modest amount of land sufficient to sustain their households. Over time, smallholders and peasants became the most free rural farmers, capable of owning land independently or farming rented parcels with fewer restrictions. The size of holdings for smallholders and peasants fluctuated over centuries but often ranged from 10 to 20 hectares, increasing during the Early Modern Period.

Characteristics of smallholders:

- Smaller land plots than villeins.

- More freedom and often land ownership.

- Agrarian subsistence and modest surplus production.

The term serf is more complex. Derived from the Latin servus meaning slave, it originally referred to unfree laborers who were legally bound to the land after the Norman Conquest. Serfs formed a significant portion of the rural population, with about 10% of households post-1066 still comprising slaves or close to that status. Over time, “serf” broadened as a category for the least free agricultural workers. Serfs differed from tenant farmers and peasants due to their lack of freedom to leave the land, restricted rights, and obligations to lords.

Typical legal and social restrictions on serfs included:

- Inability to leave the land without lord’s consent.

- Prohibition from hunting or accessing forests.

- Restrictions on carrying weapons or hiring labor.

- Being subject to levies or dues imposed by lords.

- Their status could be inheritable or tied to specific manorial customs.

Although some serfs might have small plots they worked themselves, they were generally not freeholders. Their servitude was a legal condition tying them to the lord’s estate. This made them distinct from free peasants, tenant farmers, and smallholders, who retained various degrees of independence.

| Category | Land Status | Freedom Level | Typical Land Size | Obligations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peasant | Varied (own/rent/work) | Variable | Varied | Labor/Rent in some form |

| Tenant Farmer | Rents land | Moderate | Often 15-30 acres or more | Rent, service labor |

| Smallholder | Owns or rents small plots | Relatively free | 5-15 acres typical | Minimal to moderate obligations |

| Serf | Works lord’s land, limited ownership | Least free | Small plots if any | Bound labor, dues, restricted movement |

In short, peasants form the broad group of agricultural workers. Tenant farmers are peasants who rent land. Smallholders are tenant farmers working small plots, often with more freedom. Serfs are unfree peasants bound by law and custom, heavily restricted and tied to their lords’ land.

- “Peasant” is a broad category of rural agricultural workers.

- Tenant farmers rent land, often owing labor or rent to landlords.

- Smallholders cultivate small land parcels, frequently with more autonomy.

- Serfs are legally bound to land, with limited rights and mobility.

- These distinctions reflect varying social hierarchies and land tenure systems in medieval Europe.

What Exactly Was the Difference Between a Peasant, a Serf, a Smallholder, and a Tenant Farmer?

When you hear the words peasant, serf, smallholder, and tenant farmer, you might imagine a tangled mess of medieval jargon. But fear not! These terms are distinct, each with its own meaning, status, and nuances in the agricultural world. Let’s dig in and plow through their differences with some historical dirt and clarity.

Firstly, a peasant is the broadest category here. Think of them as the backbone of agrarian society. The word traces back to Latin pagus, meaning countryside or rural area. Practically, a peasant is anyone who works the land, whether they own it, rent it, or are tied to it in some way. It’s a catch-all term, kind of like calling someone an “office worker” without specifying their role.

Serf: The Least Free in the Medieval Village

The serf is the class that suffers the most from bad press—and medieval restrictions. Originating from the Latin servus, meaning slave, serfs were initially actual slaves before evolving into a kind of tenant farmer with almost no freedom.

Serfs typically worked the lord’s land and were legally bound to it. They could not leave without permission—a fact that drastically limited their freedom. Hunting was often forbidden. Sometimes they weren’t allowed to carry weapons or hire help. This position was often inherited, so if your ancestors were serfs, congratulations? Your family line was stuck to that patch of land like gum on a shoe.

Over time, the term “serf” blurred into a catch-all for medieval tenant farmers, but originally, it referred to the least free farmers.

Tenant Farmer: Renting Their Patch of Dirt

Unlike serfs, tenant farmers rented their land. This is critical: they didn’t own it but lived and worked on it under an agreement. This agreement wasn’t just about money; often, a tenant farmer had to work a couple of days a week on their lord’s land instead of paying rent in cash. This kind of rent—service rent—was standard at the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, when most early medieval farmers were tenant farmers.

Tenant farmers stood somewhere between serfs and free men. They were not bound to the land forever, as serfs were, but neither were they fully free. Their contracts could vary, sometimes lasting generations, sometimes subject to strict conditions. You might hear tenant farmers described as wage farmers—they’re paid in land and pay back with labor.

Smallholder: The Little Land Boss

Within the tier of tenant farmers, the smallholder was one of the smaller-scale types. While a villein, a larger tenant farmer, held about 30 acres, smallholders usually managed between 5 and 15 acres. These were the hardworking unsung heroes of the village who cultivated just enough land to sustain their families and a little extra.

Interestingly, smallholders and peasants overlap somewhat—the distinction often depends on nuances of land ownership and social status. Smallholders generally owned or held sustainable parcels of land. Unlike serfs or many tenant farmers, smallholders enjoyed a relatively higher degree of freedom, and their landholding could grow or shrink over time.

So, How Do These Categories Fit Together?

| Type | Land Ownership | Freedom Level | Typical Land Size | Rent or Obligation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peasant | Varies (owner, renter, bound) | General term, broad freedom range | Varies widely | Varies |

| Serf | Usually no ownership | Legally bound to land, low freedom | Small plots or labor on lord’s land | Labor obligation, restricted activities |

| Tenant Farmer | Rents land, does not own | Contracts define freedom, more free than serfs | Varies; includes villeins (~30 acres) | Rents often paid by work/service |

| Smallholder | Often owns or holds small plot | Relatively free | 5–15 acres typically | Usually none or minimal obligations |

To sum it up: a peasant is the umbrella term for all agrarian workers. A serf is the least free kind of peasant, legally tied to a lord and land. A tenant farmer rents land and pays rent with labor or money, having more personal freedom but not full ownership. Meanwhile, a smallholder generally owns a modest parcel and enjoys a decent degree of independence.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding these distinctions helps us see how medieval rural life really worked. It isn’t just romanticized images of peasants in rags or lordly oppression. Instead, it’s a complex web of social structures and land relations that shaped entire communities.

Curious about what type you’d be in medieval times? Would you be a serf stuck on your lord’s land, or a smallholder with your own modest farm? The nuances matter—they affected daily life, legal rights, and social status.

So next time you read about medieval farming, remember: not all peasants are created equal.