A “peasant” is specifically defined as a member of the lowest social classes in a medieval rural society, primarily engaged in subsistence farming under a feudal system. They cultivated land they typically did not own, worked in exchange for protection, and contributed taxes or labor obligations to their lord.

Medieval peasants existed within a strict social hierarchy and were not all equal. Some peasants had higher status based on family history or the productivity of their allotted land. Their role amounted to more than simple farming. They operated within a communal land system controlled by feudal lords. Peasants received land to cultivate enough food for survival, paying the remainder as tax.

Below peasants were cotters, who lived in small dwellings and farmed minimal plots mainly for subsistence. Peasants belonged to a status above cotters but were subject to obligations like labor services or rents payable to their lord.

Historian Chris Wickham describes peasants as settled cultivators performing agricultural labor personally and maintaining control over their work efforts. This distinguishes peasants from slaves or wage laborers who had no autonomy in their labor. Some peasants owned small plots (“small peasants”) while others were tenants farming leased land. Wealthier peasants might employ laborers or tenants, blurring lines between peasantry and landowning classes.

The category ends when a peasant accumulates enough land to stop direct farming and becomes a medium landowner. Thus, the term “peasant” has precise socio-economic boundaries linked to agrarian labor, tenancy, and social obligations within the feudal order.

We no longer use “peasant” because modern economic systems have abandoned feudal structures and rigid class distinctions. Capitalism enables widespread land ownership, allowing individuals or corporations to buy and sell land freely. This mobility contrasts with the medieval system where land tenure determined social status and obligations.

In today’s context, there is no direct social class matching medieval peasants. Some compare the working or middle class to peasants due to their economic position, dependent largely on wages and subject to taxation. However, modern living standards and economic freedoms far surpass those of the medieval peasantry.

Usage of the word “peasant” diminished gradually. Historically, it was not always the preferred term even in medieval times. For example, English sources on the Peasant Revolt referenced revolters as “commoners” or “vile,” not using “peasant” contemporaneously. The word “peasant” is somewhat anachronistic, applied retroactively by later historians to describe certain agrarian classes.

Official abandonment of the term occurred at different times and regions. In Finland, legal reforms in 1906 ended recognizing peasants as a distinct estate after many people no longer belonged to traditional estates. Western Europe dropped the term centuries earlier. Yet in Eastern Europe, political parties named after peasants existed well into the 20th century, reflecting a more persistent social identity.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | Lowest rural class in medieval society, subsistence farmers under feudal obligation |

| Land Ownership | Generally did not own land; farmed communal or lord-owned lands |

| Labor | Engaged in personal agricultural work; controlled own labor unlike slaves |

| Social Hierarchy | Above cotters, below landowners; some variation within peasant class |

| Why Term Faded | Disappearance of feudal system; rise of capitalism and land ownership freedom |

| When Term Stopped | Varied by region: 1906 in Finland; much earlier in Western Europe; persisted longer in Eastern Europe |

- Peasants were medieval rural workers tied to land they did not own, living under feudal obligations.

- They personally labored on land to produce subsistence crops, paying taxes or rents in return.

- Modern economy’s land ownership and wage labor systems have replaced the medieval peasantry class.

- The word “peasant” is largely historical and context-dependent, not used officially today.

- The term’s usage faded regionally at different times, largely with the end of feudal estates and modern legal reforms.

What Exactly Defines a “Peasant”? Why Don’t We Call People That Anymore? When Did We Stop?

The short answer? A “peasant” was a very specific social and economic role tied deeply to medieval village life and the feudal system. Today, the word feels outdated, even a bit rude. But why? And when did we stop calling folks peasants? Let’s dive in.

First off, what exactly defines a peasant? It’s not just someone toiling on the land; it’s a unique social class that fit into the medieval, rigid hierarchy. Imagine a medieval village: peasants sit near the bottom of the social pyramid, ranked just above cotters—those folks who lived in tiny cottages with barely a garden’s worth of food to scrape by. Peasants typically farmed land, but—and here’s the twist—they usually didn’t own it personally.

Ownership was a tricky issue. Land officially belonged to the village lord or the crown. The peasants worked the fields communally, meaning that while they cultivated the soil, they had to hand over a share of their crop as taxes or rent. In exchange, the lord offered protection from marauders or rival lords. So, peasants were workers embedded in a system of mutual obligation.

According to historian Chris Wickham, a peasant was basically “a settled cultivator who grows food mainly for subsistence and controls their own labor.” This definition introduces nuance: unlike slaves or wage workers, peasants had some say over their work, but not full freedom or property rights. Some peasants owned small parcels of land (“small peasants”), others rented land, and some even had laborers working parts of their land. If a peasant acquired enough land to stop laboring personally, they essentially graduated into the rank of a “medium landowner”—no longer a peasant.

So, peasants were complex. They weren’t just poor farmers but part of a complicated social order balancing ownership, labor, and survival.

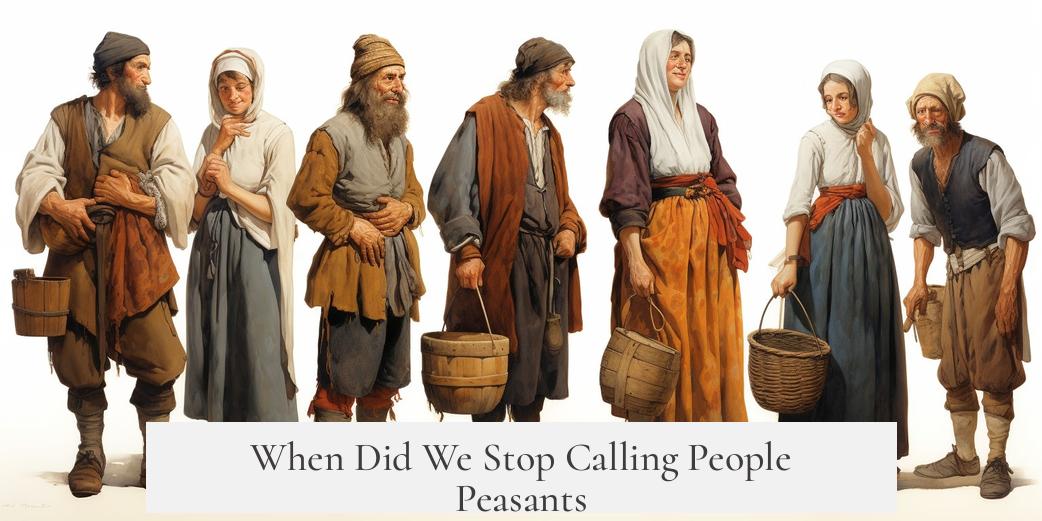

Why Don’t We Call People Peasants Anymore?

Here’s a no-nonsense fact: our modern economic system doesn’t have peasants. The feudal order that pigeonholed peasants into fixed roles evaporated centuries ago. Today, land ownership is accessible in capitalist societies—you can buy, sell, or rent land regardless of your family background.

Does that mean peasants disappeared completely? Sort of. In a playful comparison, some argue that America’s middle class now plays the role peasants once did: they work hard, pay taxes, bills, and loans, and keep the economic engine running. But—and this is a big but—their standard of living is significantly higher than that of medieval peasants.

Calling a contemporary farmer or rural laborer a “peasant” would miss both the historical and social nuances involved. It also carries a tone of condescension that no modern society wants to endorse.

When Did We Stop Calling People Peasants?

Here is where history gets a bit fuzzy. The term “peasant” itself is somewhat of a retroactive label, imposed by modern historians looking back at the past. Medieval records rarely used the word in the way we do now. Take England’s famous Peasant Revolt of 1381. The rebels weren’t called peasants at the time. They were labeled “vile,” “rude,” and “common”—words loaded with disdain but no direct “peasant” marker.

Interestingly, countries phased out the official use of the term at very different times. Finland, for example, legally stopped using “peasant” in 1906 when it reformed its political system to include more of the population outside traditional estates. In Western Europe, the term stopped being common centuries ago, but in Eastern Europe, political parties named after peasants existed well into the 20th century. That stuck because rural traditions and class systems lingered longer in some regions.

A Unique Perspective on the Peasant Identity

So what makes the label “peasant” more than just a dusty medieval title? It’s the fact that it ties labor, land, and power into one neat but restrictive social package. Peasants had some control over their work but little over their land or futures. The system kept them tethered to their lords and limited their social mobility.

Imagine you are a medieval peasant. You wake at dawn, work through the sun-baked fields, and split your harvest between your family’s survival and the lord’s demands. Your life is precariously balanced on the land’s yield, village politics, and sheer luck against invasion or famine. Your feet are planted firmly in a world where your labor is your legacy, but your freedom is constrained.

Now imagine the modern middle class. You still work hard, pay your share, but you own your home, drive a car, and have options your medieval counterpart couldn’t dream of. That’s why calling anyone a “peasant” now feels almost an insult—because the concept implies limits and hardships that modern society refuses.

What Can We Learn From This?

Understanding peasants and why the term fell out of favor helps us appreciate how economic systems shape identity. Labels reflect more than work—they reveal power dynamics, opportunities, and social mobility. The shift away from “peasant” shows progress in ownership, rights, and living standards.

Next time you hear “peasant,” remember: it’s a snapshot of a world where most people were tethered to the land, controlled by forces beyond themselves, and struggling to survive day to day. It’s a sharp contrast to today’s fluid economy and evolving social classes.

Would we be as comfortable calling someone a peasant today if they faced such constraints?

Probably not. Because our language—and society—have moved on.

What defined a “peasant” in medieval times?

Peasants were mostly farmers who did not own land outright. They worked communal farmland under a lord and paid taxes with their crops. They had some control over their labor but were part of a strict social hierarchy.

Why don’t we use the term “peasant” to describe people today?

Modern economies allow land ownership across classes, unlike medieval times. The old peasant role vanished as society moved away from feudalism. Today’s lower and middle classes have better living conditions and different social roles.

When did people stop being called peasants?

The term “peasant” wasn’t common during medieval times. It was applied retroactively. In places like Finland, it officially fell out of use by 1906. Western Europe stopped using it centuries earlier, though it persisted in some Eastern European politics.

Were all peasants equal in status?

No, peasants varied in prestige depending on family and land yield. Some owned small plots or had tenants, while others worked only as laborers. Large landholders among peasants could rise above their class.

How did peasants differ from slaves or wage laborers?

Peasants usually controlled their own labor on the land they cultivated. Unlike slaves, they were not owned outright, and unlike wage laborers, they were tied to land and subsistence farming rather than paid employment.