The fall of Sparta results from a long, gradual decline marked by military defeats, demographic troubles, financial struggles, and failed policies. Its loss of empire, manpower shortages, and foreign pressure eroded Spartan dominance over centuries until Rome’s control in the 2nd century BC.

Following the Peloponnesian War, Sparta rose as a dominant force in Greece, controlling Athens and parts of the Aegean, Asia Minor, and Western Greece. However, the Persian-backed Corinthian War from 395 to 386 BC dealt a severe blow to Spartan naval power and overseas territories. The peace treaty forced Sparta to cede Asian Minor states to Persia, leaving it as the strongest power only on the Greek mainland.

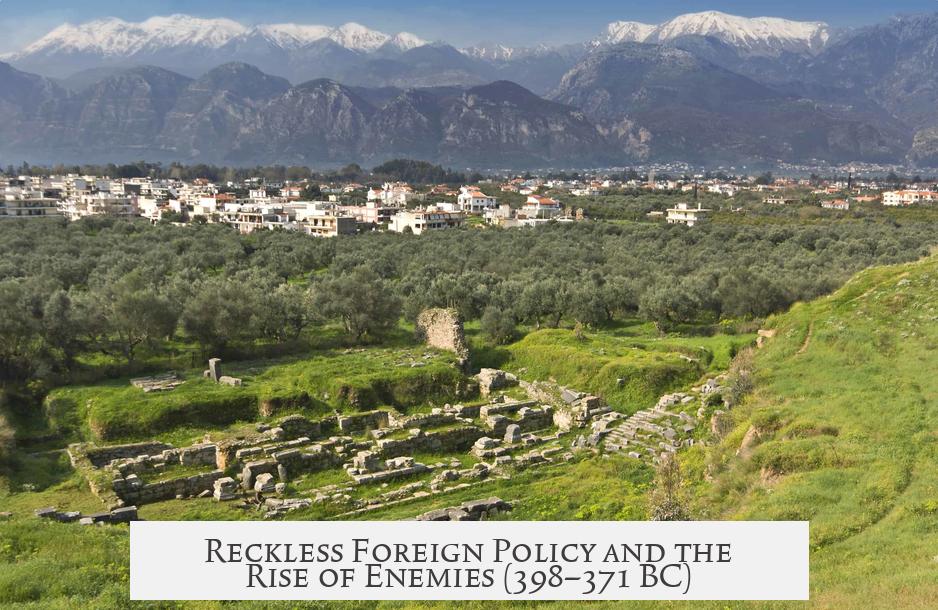

Sparta’s foreign policy under King Agesilaos proved reckless. His focus on Thebes and aggressive campaigns alienated many Greek states. This behavior united former rivals against Sparta. Athens defeated Sparta’s final naval attempt in 375 BC. This defeat triggered the formation of a large 75-state anti-Spartan alliance. The most damaging event was Sparta’s occupation of Thebes in 381 BC. When Thebans expelled the garrison, the resulting war culminated in Sparta’s devastating loss at the Battle of Leuktra in 371 BC.

Leuktra was a turning point. Thebes invaded Spartan lands, plundering Lakonia. They liberated Messenia, a critical Spartan territory for centuries, cutting Spartan land by half.

Another key factor was demographic decline, referred to by Aristotle as oliganthropia, the shrinking number of full Spartan citizens. The population of adult male Spartans plunged from roughly 8,000 in the 6th century BC to around 1,200 by 371 BC. About 400 died at Leuktra. The reduction crippled Sparta’s ability to field armies and maintain control over their land. By the 3rd century BC, only about 100 full citizen households remained. Despite this crisis, Sparta resisted reforms that might have increased manpower.

Financial strain compounded Spartan problems. Lacking strong trade or industry, Sparta struggled to fund its military and social system. Kings Agesilaos and Archidamos even worked as mercenaries abroad to raise funds. Attempts to reconquer Messenia to restore land and citizen numbers failed. Sparta’s refusal to accept Messenian independence trapped them in a costly, unwinnable conflict.

After Leuktra, military setbacks continued. Sparta narrowly avoided conquest by Demetrios the Besieger in 294 BC and fought off Pyrrhos of Epiros in 272 BC. In the mid-3rd century BC, reforms under Agis IV and Kleomenes III temporarily revived Sparta by redistributing land and reforming the army. However, their efforts collapsed at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC, where Macedonian forces under Antigonos III Doson defeated the Spartans. Antigonos was the first enemy to enter Sparta victorious, marking the definitive end of Spartan independence as a major power.

Nabis seized power in 207 BC, ending the traditional dual kingship and trying to restore Spartan strength. Despite this, Sparta could not match its rising neighbors or Rome. In 195 BC, Rome stripped Sparta of its powers. Nabis remained until 192 BC when assassins murdered him, and Sparta soon fell under control of the Achaian League. From this point, Sparta ceased to be an independent power.

In essence, Sparta’s fall was not sudden. It was a drawn-out decline caused by a mixture of military defeats, poor diplomacy, internal population decline, financial weakness, and political inflexibility. Single city-states like Sparta could not compete against larger Hellenistic kingdoms or Rome by the 2nd century BC.

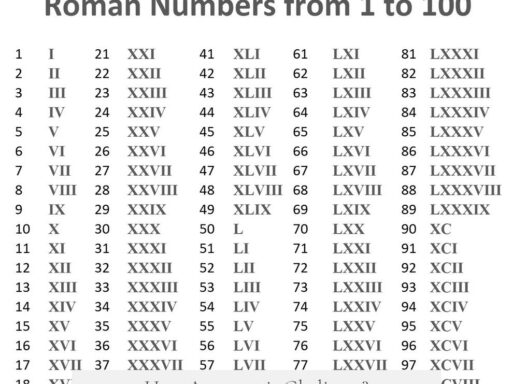

| Cause | Details |

|---|---|

| Loss of naval/overseas power | Corinthian War (395-386 BC); loss of Asian Minor territories to Persia |

| Reckless foreign policy | Aggressive campaigns, occupation of Thebes, formation of anti-Spartan alliances |

| Demographic decline | Drop from ~8,000 to ~1,200 male citizens; inability to field armies |

| Financial struggles | Lack of trade, costly military efforts, mercenary kings abroad |

| Military defeats | Leuktra (371 BC), Sellasia (222 BC), pressure from Macedonians and Romans |

| Loss of independence | Stripped of power by Rome (195 BC), fall under Achaian League (192 BC) |

- Sparta’s decline was gradual, stretching from the late 5th century BC to the Roman era.

- Military losses and diplomatic errors weakened Spartan dominance.

- Population decline critically reduced its military and political power.

- Financial inability stifled efforts to recover lost status and territory.

- Final conquest by Rome ended Sparta’s sovereignty.

What Caused the Fall of Sparta? A Slow Fade Rather Than a Dramatic Collapse

The fall of Sparta wasn’t a single lightning strike but more like a slow burn. Instead of collapsing overnight, it trailed off over centuries, eroded by battles lost, dwindling citizens, bad choices, and shifting power dynamics until the Romans stepped in and sealed the deal in the 2nd century BC.

Imagine trying to pinpoint the exact moment a giant oak tree falls in a storm. It creaks and groans for hours before toppling. That’s Sparta’s story: a gradual fading rather than a sudden crash.

Loss of Naval Power and the Overseas Empire (399–386 BC)

After spanking Athens in the Peloponnesian War, Sparta looked like the boss of Greece. It held the Aegean, Asia Minor’s Greek cities, and western Greece under its thumb. Sweet, right?

But here’s the catch: Sparta’s empire rested partly on naval power, and it sucked at sea battles. The Persian-backed Corinthian War was like Sparta’s kryptonite. It smashed their naval fleet and forced Sparta to hand over all Greek cities in Asia Minor back to Persia during the peace deal.

Sure, Sparta stayed the biggest fish on the Greek mainland pond, but the loss of overseas territories was the first major chink in its armor.

Reckless Foreign Policy and the Rise of Enemies (398–371 BC)

Sparta’s King Agesilaos was obsessed with Thebes. He basically chased Thebes everywhere, throwing temper tantrums in the form of wars abroad. This aggressive policy united all the Greeks against Sparta like nobody’s business.

Sparta’s dramatic overreach backfired. When they tried to reclaim sea power in 375 BC, a resurgent Athens crushed them again. In response, roughly 75 states formed an anti-Spartan alliance. Talk about making a lot of enemies quickly!

Perhaps the most infamous blunder? Stationing an occupation force in Thebes around 381 BC. The Thebans booted out these unwanted guests, sparking a war that ended disastrously for Sparta at the Battle of Leuktra in 371 BC.

Ouch. The Thebans not only won but plundered Laconia, liberated Messenia, and chopped Spartan territory in half. That was a chapter no Spartan wanted to reread.

Demographic Decline: Less Spartans, More Problems

Aristotle coined the term oliganthropia to describe the scary drop in Spartan citizen numbers. From around 8,000 adult males in the late 6th century BC, they shrank to about 1,200 by Leuktra—and lost 400 of those in battle.

By the mid-3rd century BC, only 100 full citizen households remained. Yes, 100—talk about a manpower crisis!

Instead of adapting or reforming, Spartans stubbornly clung to their rigid laws, which made reviving their citizen army exceptionally tough.

Financial Woes and Overextension

Sparta was surprisingly broke. Unlike its rivals with bustling trade and local industries, Sparta’s economy was strained.

Spartan kings, like Agesilaos and his son Archidamos, moonlighted as mercenaries abroad just to bring in some cash. It’s like a retired general picking up a side hustle to pay bills.

The attempt to reconquer Messenia—a vital land for boosting wealth and citizen numbers—failed miserably. Sparta couldn’t accept Messenian independence, locking itself in a never-ending war that drained resources.

Military Defeats and Lost Autonomy After Leuktra

The defeat at Leuktra was Sparta’s turning point. Afterwards, their grip on the Peloponnese slipped dramatically.

Sparta dodged survival by the skin of its teeth against Demetrios the Besieger in 294 BC and later resisted Pyrrhos of Epiros in 272 BC.

There was a brief flash of hope under reformers Agis IV and Kleomenes III around 240 BC, who tried fixing the mess with land redistribution and army reform. Unfortunately, their newly rebuilt army was smashed by Macedonians at Sellasia in 222 BC, when Antigonos III Doson marched victorious into Sparta itself.

That was something brand new: a foreign army storming Sparta’s home turf victorious.

Final Attempts and Total Loss of Independence (207–192 BC)

Nabis grabbed power in 207 BC, ended the royal family line, and attempted a comeback. He wasn’t exactly your average ruler: clever, ruthless, yet utterly outmatched by Greek neighbors and rising Rome.

Rome stripped Sparta of its power in 195 BC. Nabis stuck around until his assassination in 192 BC. Then, Sparta was absorbed by the Achaian League. When Rome showed up, Sparta’s fate as an independent city-state was effectively sealed.

Wrapping It Up: Why Did Sparta Fall?

“The decline of Sparta was due to a combination of powerful rivals, overambition and bad foreign policy, military defeats, demographic decline, a shortage of money, internal rivalries, and the general fact that single city-states no longer formed a large enough power base to compete with the major powers of the Hellenistic period.”

Sparta’s fall wasn’t the result of one catastrophic event, but a cocktail of factors mixed over centuries. They lost their empire, alienated neighbors, ran out of soldiers, drained their coffers, and finally could not withstand newer, bigger powers.

If Sparta had adapted—relaxed its rigid social system, reformed its finances, or been less trigger-happy in foreign affairs—history might have written a different story. But stubbornness, combined with relentless foes, led to a slow fade from being Greece’s legendary warrior-state to just another part of the Roman world.

What Can Modern Leaders Learn From Sparta’s Slow Decline?

- Don’t alienate potential allies with reckless actions.

- Keep an eye on your base: manpower/people and wealth matter just as much as military might.

- Adapt or die: rigidity in systems often leads to stagnation and collapse.

- Know when to cut losses or negotiate peace instead of endless conflict.

After all, even the toughest warriors can’t fight forever without reinforcements and strategy.

So, next time you think the Spartans just fell flat in one battle, remember: they slowly stumbled, like a marathon runner who forgot to pace themselves.