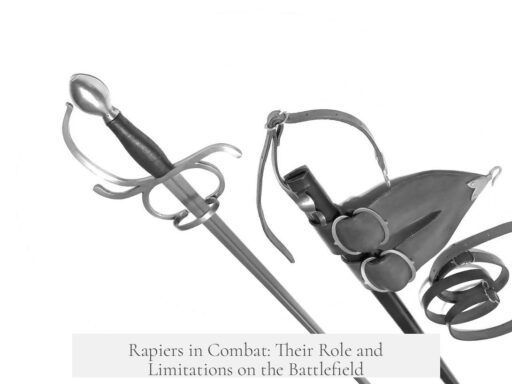

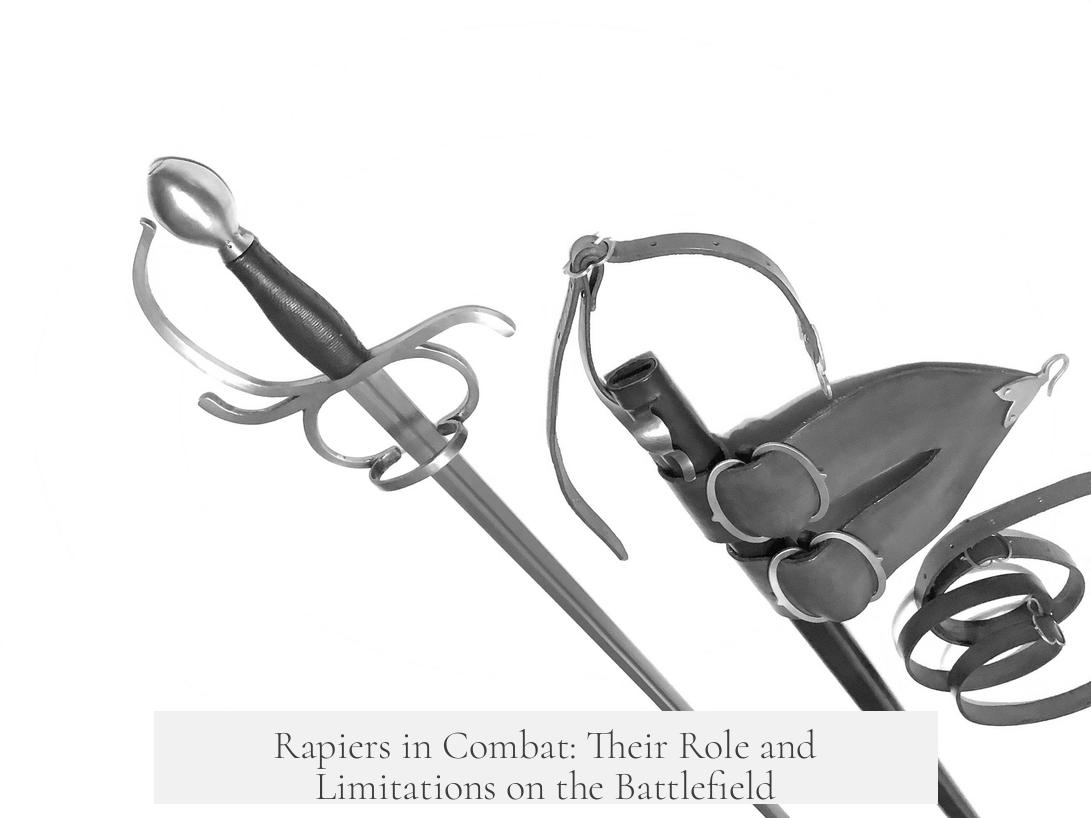

Rapiers were generally not used on the battlefield as primary weapons. They emerged around the 1500s as civilian weapons designed for self-defense and dueling rather than warfare. Their design prioritized agility and precision over battlefield durability and mass combat effectiveness.

The rapier developed as the Spanish espada ropera, or “dress sword,” combining elegance with practical use for civilian self-defense. Unlike medieval swords, rapiers featured slender, sharply pointed blades ideal for thrusting, enabling skilled users to exploit weak points in armor or avoid heavy wounds entirely. However, this specialization made the rapier unsuitable for heavy combat situations.

One major limitation was the rapier’s fragility under battlefield conditions. Its thin blade, intended for quick, precise attacks, risks snapping against heavier swords or polearms. This fragility renders the rapier impractical for formation fighting, where soldiers must defend themselves and comrades from sustained blows. Battlefield swords needed durability for cutting and hacking as much as thrusting.

The rapier’s elaborate crossguard offered some hand protection and negated the need for gauntlets or shields. This feature aligned well with civilian combat, where mobility and style mattered. In contrast, soldiers typically relied on gauntlets and shields during battle. Rapiers also lacked the broad cutting edge to cleave through armor or deliver powerful blows required for battlefield effectiveness.

Historical exceptions exist. Spanish Conquistadors in the Americas frequently carried rapiers during small-scale skirmishes against lightly armored foes. Their enemies’ limited armor made the rapier’s thrusting attacks more practical. During the English Civil War, cavalry and officers occasionally wore rapiers alongside heavier weapons. Museums hold examples of pattern swords indicating limited battlefield use, but these were not the primary weapons for mass combat.

The battlefield sword of the 1600s was the side sword or basket-hilted sword. These designs were heavier, sturdier, and capable of both cutting and thrusting. Side swords retained some narrow-point features but prioritized durability for combat in close formations. In contrast, the rapier was more delicate and longer, emphasizing finesse over brute strength.

Smallswords, which appeared later, were even more delicate than rapiers and used exclusively for dueling, never for warfare. Soldiers chose weapons to maximize survival on the battlefield, favoring warhammers, axes, and maces against armored opponents. These weapons delivered blunt force trauma or could penetrate armor where swords struck ineffectively.

Armor trends also influenced weapon choice. In the 1400s and 1500s, full plate armor protected most of the body. Swords struggled to penetrate this, so soldiers carried weapons designed to crush or puncture. Renaissance armor left limbs more exposed, offering more targets for lighter swords like the side sword but still demanding robustness.

Despite common belief that rapiers are exclusively thrusting weapons, they can cut as well. Users report rapiers hold up reasonably under proper technique, but this does not translate into suitability for chaotic, heavy battlefield fighting. The finesse and precision required for effective rapier combat suit duels and self-defense far better than large-scale warfare.

| Aspect | Rapier | Battlefield Sword (Side Sword) |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Thin, long blade; elaborate crossguard; light | Heavier, broader blade; basket hilt for hand protection |

| Usage | Civilian self-defense, dueling | Military combat, cutting and thrusting |

| Durability | Fragile under heavy impact | Robust, suitable for formation fighting |

| Armor Interaction | Effective against lightly armored targets | Designed to exploit armor weaknesses |

- Rapiers are primarily civilian weapons, not battlefield swords.

- Their thin blades lack durability for mass combat or formation fighting.

- Side swords and basket-hilted swords were preferred on battlefields.

- Some limited battlefield use occurred, especially with Spanish Conquistadors.

- Armor evolution influenced sword design and choice during 1400–1600s.

Were Rapiers Ever Used on the Battlefield?

Short answer: Rapiers were mostly not used on battlefields. They were primarily crafted as elegant civilian weapons, designed for self-defense and dueling rather than brutal warfare. While a few exceptions exist, the rapier generally doesn’t fit the practical requirements of combat on the open field.

Now, why is this the case? Let’s dive deeper into the fascinating history, design nuances, and battlefield realities surrounding the rapier. Spoiler alert: it’s quite a blend of fashion, function, and tactical limitations.

Rapier: The Civilian’s Stylish Companion

The rapier was born around 1500 as the Spanish espada ropera, literally “dress sword.” Think of it as a weapon with flair — meant to complement a gentleman’s ensemble while also providing practical self-defense. Unlike the chunky swords of medieval knights, the rapier dazzled with elaborate crossguards and slim, slender blades.

Its design deliberately avoided the need for bulky gauntlets or shields. This choice aligns with civilian life, where carrying heavy armor was neither practical nor aesthetically pleasing. In other words, the rapier was the urbanite’s sword—ready for a duel or a close call with a pickpocket, but not the chaos of a clashing battlefield.

Consider the contrast: soldiers didn’t want to lose their gauntlets or shields, essential for survival. The rapier’s delicate elegance worked against it here.

Why the Rapier is Unsuitable for the Battlefield

Battlefield combat is brutal and rough. Soldiers fought in tight formations, smacking their sword edges against enemy blades and armor. In this context, a rapier is near useless. Its thin blade would easily snap under the stress, like a twig cracking in wind.

“When fighting in formation, a rapier is nigh on useless, because it would snap like a stick if met with heavier blade.”

Moreover, during the 1400s and 1500s, the presence of armored knights made swords less dominant. Soldiers favored heavier weapons such as maces and warhammers that could crush or pierce armor. Full suits of medieval armor protected vital areas fully, demanding weapons that could deliver bone-crushing blows rather than fine stabs.

In the 1600s, armor evolved but became more partial—covering mostly the torso and leaving limbs relatively exposed. This meant side swords, heavier and broader than rapiers, were effective, used to slash at vulnerable limbs or thrust into gaps in armor. The rapier, by contrast, was lighter and narrower, optimized more for precise thrusts than wide cuts or smashing blows.

Side Swords vs. Rapiers: Battle-Ready or Not?

The side sword is the militarized cousin of the rapier. With a slightly broader and heavier blade, it was better suited to battlefield situations, maintaining a tapered point for thrusting but offering more durability and cutting ability.

The difference is subtle but vital: side swords could handle the roughness of combat formations. Rapiers focused on finesse, precision, and dueling in controlled environments.

So, while rapiers and side swords look somewhat alike, the side sword holds the edge in battlefield suitability.

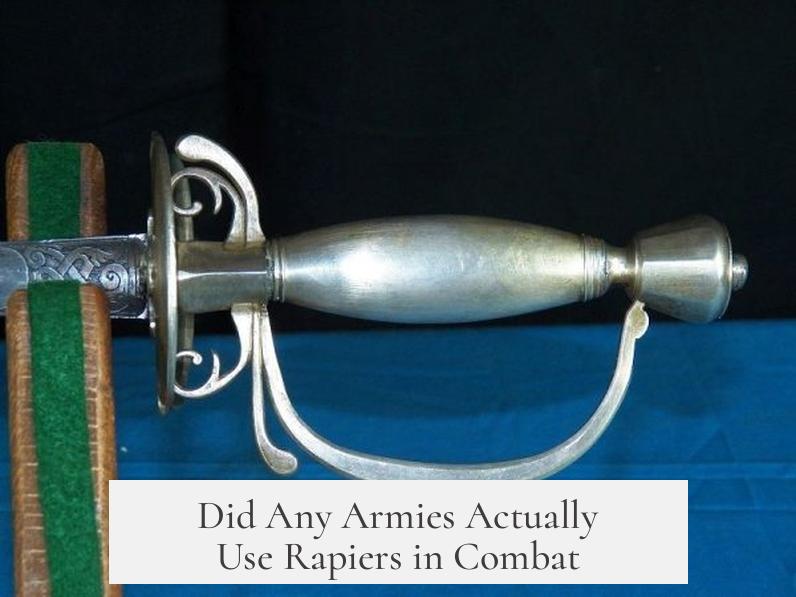

Did Any Armies Actually Use Rapiers in Combat?

Despite their limitations, rapiers found niche battlefield uses. The Spanish Conquistadors in Latin America frequently carried rapiers. Their enemies often lacked heavy armor, making the rapier’s long reach and thrusting power effective in those skirmishes.

Similarly, during the English Civil War, soldiers armed themselves with rapiers alongside other weapons. However, these soldiers often wore buffalo hide armor offering some protection but not full medieval plate. In such partial armor scenarios, the rapier could function with moderate effectiveness.

Still, these examples were exceptions, often in irregular warfare or smaller conflicts rather than grand, pitched battles with heavily armored foes.

Small Swords: The Later Evolution

We often confuse rapiers with later weapons like the smallsword. The smallsword appeared in the 1700s and 1800s, designed solely for dueling. It was even thinner and lighter than the rapier and rarely, if ever, used in battle.

Battle-ready swords were heavier. Soldiers preferred weapons that could chop or deliver reinforced thrusts through armor. Small swords belong firmly in the gentleman’s duel arena, not the battlefield.

Can a Rapier Survive a Battle?

Contrary to popular belief, rapiers are not as fragile as foils or other sport fencing blades. Experts who have trained with real rapiers affirm that these swords can endure combat if wielded using proper technique. However, their design and the combat style they support — precise, calculated thrusts — don’t lend themselves well to the chaotic and violent nature of battlefield fighting.

Imagine a rapier in a wild clash of armored soldiers, shield bashes flying and heavy swords swinging. Even a sturdy rapier would face a tough time. But in a duel, or a skirmish involving lightly armored opponents, the rapier’s agility and reach shine.

So, Were Rapiers Ever Used On the Battlefield?

The answer is mostly no—but with fascinating exceptions. Rapiers primarily shine as civilian weapons for self-defense and duels, not as mainstays in army arsenals. Their thin blades and finesse-oriented design clash with the brutal reality of formations, armor, and battlefield weaponry demands.

The side sword, heavier and sturdier, stands as the battlefield counterpart, while the smallsword later emerged purely for dueling. Armies like the Spanish Conquistadors and some English Civil War troops found situational use for rapiers, especially when facing less armored foes or fighting more loosely organized conflicts.

In modern eyes, the rapier is often romanticized thanks to swashbuckling tales and theatrical duels. But the truth reveals a weapon more suited for stylish self-defense than spearheading charges or slashing through ranks.

Final Thoughts: The Rapier’s Niche in History

- Primarily a civilian weapon, designed for elegance and practical self-defense.

- Its thin blade and light weight make it ill-suited to brutal battlefield combat.

- Side swords and heavier weapons dominated actual battlefields of the 1500s–1600s.

- Exceptions like Spanish Conquistadors using rapiers in lightly armored skirmishes.

- Small swords follow as later pure dueling weapons, not battlefield swords.

So next time you see a rapier in a movie or museum, remember: it’s a symbol of finesse, civility, and precision. Not the raw, unyielding steel of the battlefield—more the urbane gentleman’s silent partner in a dangerous world.

Now, would you pick a rapier or a side sword if you ever find yourself storming a castle? Tough choice — but history’s lessons say, think twice before trusting that slender blade in a fight for survival!