Triumph of the Will (1935) is indeed an innovative film in terms of its cinematic techniques, though this innovation is inseparable from its function as Nazi propaganda. The film’s groundbreaking use of cinematography, editing, and sound design elevated propaganda filmmaking to an unprecedented artistic level. Yet, its creative accomplishments serve a clear ideological purpose: to glorify Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Any appraisal of its innovation must also acknowledge the film’s deeply troubling content and legacy.

The context of Triumph of the Will is essential to understanding its dual nature as artistic achievement and propaganda. Propaganda films in Nazi Germany were common, but these films often embraced ambitious filmmaking techniques. Directors were given a significant degree of artistic freedom in how they executed their vision, though the underlying message remained strictly controlled. Triumph fits this pattern, blending propaganda with elements from popular and experimental German cinema of the time.

German film before Triumph provided a fertile ground for innovation. The Bergfilme genre showcased adventurous cinematography, including dynamic tracking shots behind skiers. Early city-symphony documentaries sought to create poetic portraits of urban life through rhythmic editing and visual metaphors. Expressionist films from the 1920s pushed boundaries with dramatic lighting and distorted perspectives. Leni Riefenstahl emerged in this rich cinematic tradition, having worked as an actress in Bergfilme and absorbing influences from expressionism and city-symphonies.

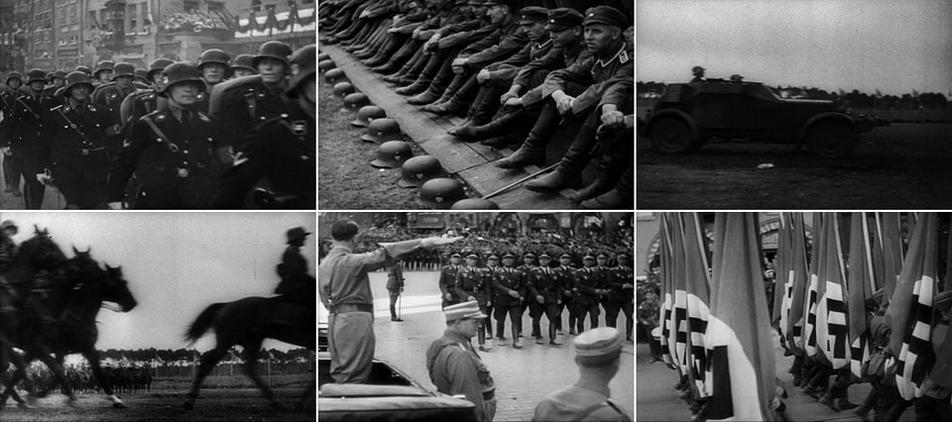

Drawing on these predecessors, Riefenstahl created a film that combined poetic imagery with politically charged editing and grand scale. She used sweeping camera movements, dramatic low angles, and carefully timed cuts to depict Hitler and his followers as heroic and unified. Unlike conventional documentaries—which simply record reality—Triumph deliberately intertwines music, diegetic sound, and imagery to evoke emotion and reinforce its ideological message.

This artful construction is central to the film’s recognised innovation. Intentionality defines Triumph of the Will. Riefenstahl orchestrated every visual and auditory element to persuade viewers of the Nazi Party’s might and righteousness. For example, she juxtaposes intimate shots of Hitler engaging with supporters against vast images of anonymous crowds, suggesting both a personal connection and mass power. Sound is heightened by the rhythmic pounding of marching boots, amplifying a sense of unstoppable force. Riefenstahl herself published a booklet in 1935 explaining the purpose behind key shots, underscoring the film’s meticulous design.

| Technique | Effect and Innovation |

|---|---|

| Tracking shots | Dynamic movement following crowds and marches |

| Low-angle shots | Heightened stature of Hitler and soldiers |

| Cross-cutting | Connecting personal warmth to mass enthusiasm |

| Sound design | Combining music with diegetic sound for emotional impact |

Despite these artistic breakthroughs, Triumph must also be seen foremost as Nazi propaganda. It was part of one of history’s largest propaganda efforts, backed with substantial funding and organization. Riefenstahl’s film explicitly aims to glorify fascism and Hitler, making it impossible to separate from its hateful content. This legacy complicates appreciation of the film as a cinematic work.

The film’s influence is undeniable. Filmmakers and cultural creators have referenced its visual style and motifs repeatedly. The imagery used to depict totalitarian power in Triumph serves as a blueprint for villainous regimes in movies like Star Wars and even in animated films such as The Lion King. This lasting impact illustrates how cinematic language forged in propaganda can transcend its original context but always carries problematic associations.

In short, Triumph of the Will represents a notable innovation in film technique. However, this innovation is inseparable from its role as an effective and disturbing piece of propaganda. Its legacy challenges viewers and scholars to recognize cinematic artistry while confronting the ideologies it promotes.

- Triumph combined diverse filmmaking traditions, including Bergfilme, city-symphony, and expressionism.

- Riefenstahl’s deliberate construction and intentionality set new standards in propaganda film.

- The film’s artistic achievements amplify a clear Nazi ideological message.

- Its visual style influenced depictions of authoritarianism in later films and media.

- The film’s legacy forces a complex engagement with both innovation and propaganda.

Was Triumph of the Will (1935) Really That Much of an Innovation in Film? Or Is This Idea Itself an Example of Nazi Propaganda?

Yes, Triumph of the Will was innovative in many cinematic aspects, but calling it purely a filmic breakthrough ignores its core role as Nazi propaganda, which shapes how we must view its so-called innovations. Now, let’s peel back the layers of this cinematic onion—without tearing up too much.

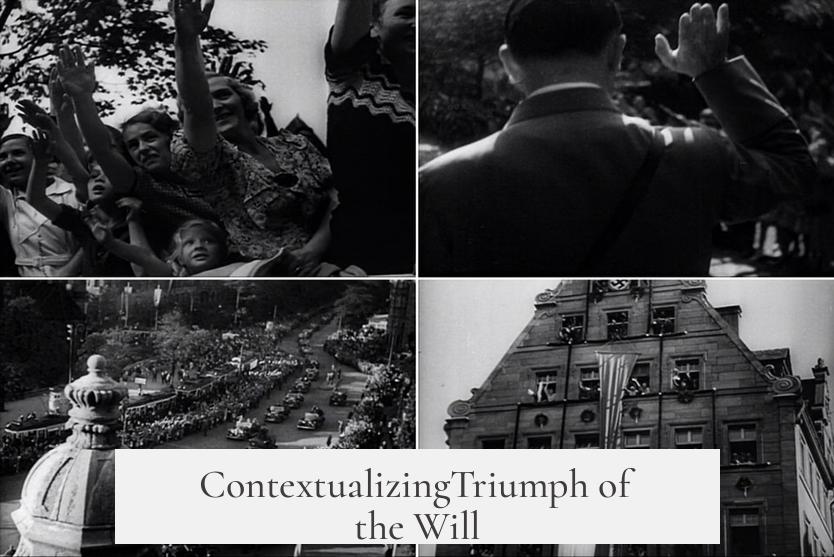

Contextualizing Triumph of the Will

First, it’s key to place Triumph of the Will in the frame of both propaganda and German cinema history. Propaganda films aren’t all stiff and dull; in fact, they often allowed directors breadth to experiment artistically, just under the thumb of rigid thematic constraints. Think of it this way—like being given a coloring book but only allowed to use red.

German film at the time was already a hub of creativity. Genres like Bergfilme featured breathtaking shots, such as camera operators skiing behind racers—talk about dedication! City-symphony films aimed to capture urban life in poetic motion. And let’s not forget Expressionist films with their stylized visuals playing with light, shadow, and perspective. So, when Leni Riefenstahl stepped into filmmaking, she wasn’t reinventing the wheel but rather hopping onto a merry-go-round of ambitious and avant-garde German cinema.

Leni’s own journey began in this rich field. She acted in Bergfilme, absorbed Expressionist influences in childhood, and witnessed city-symphony films gaining traction. By the time she made Triumph, she was essentially standing on the shoulders of cinematic giants—armed with a belief in the Nazi ideology and a passion to encapsulate it in film.

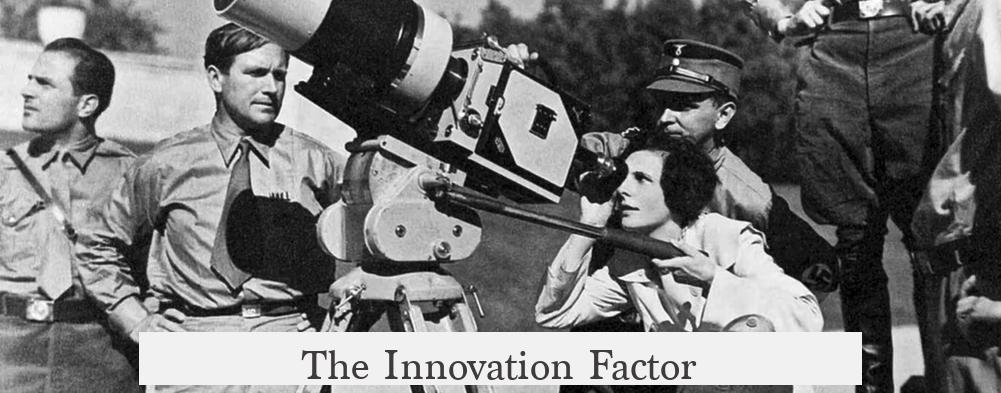

The Innovation Factor

Was Triumph of the Will a fresh new voice in film? Only if your soundtrack of innovation includes orchestras of marching boots, mountains of cheering crowds, and shots calculated to boost one political party’s image to mythical heights. Riefenstahl combined the poetic rhythms of city-symphony cinema with the sharp, purposeful editing styles pioneered by Eisenstein and Pudovkin. She blended these with a lavish budget and a keen sense for dramatic music and diegetic sound, crafting a film experience beyond mere documentation.

Here’s where intentionality steps in. Film students hear this term a lot, and it’s pure gold for understanding Triumph. Riefenstahl choreographed every shot to function as a cog in the propaganda machine. Hitler is portrayed less as a politician and more as a compelling leader—always approachable, engaging, surrounded by adoring supporters. Soldiers transform from people into near-mythic figures through thunderous marching sounds and heroic low-angle camera work. The Nazi movement itself? A titan assembled from endless shots of vast crowds and unwavering cheers.

In 1935, Riefenstahl even wrote a booklet explaining her thought process and craft decisions. Talk about being proud of your work! But this depth of control and artistic mastery served one purpose: to promote and glorify the Nazi Party.

The Propaganda Within and the Film’s Legacy

Now, let’s lay it out squarely: Triumph of the Will is propaganda. It’s part of one of the most well-funded, organized, and devastating propaganda machines of the 20th century. To claim it succeeded purely because of cinematic brilliance would be ignoring history and context. Leni was personally entwined with the Nazi party and continued to work on similar projects, such as the 1936 film Olympia, refining these techniques to glorify fascism further.

This complex legacy means watching Triumph is almost always a troubling experience—an artistic achievement overshadowed by horrific ideology. Dismissing the film outright is easy, but recognizing its impact on cinema and propaganda is crucial to understanding why it remains so notorious and studied.

Moreover, Riefenstahl’s visual language did not vanish after the Third Reich. In fact, filmmakers and creators across genres and decades have referenced her stylistic choices to depict authoritarian regimes. You’ll find echoes of her work in The Star Wars empire’s imposing rallies or even in the eerie “Hyena Parade” scenes in The Lion King. This visual shorthand for villainy owes a part of its DNA to Triumph, almost 90 years after its release.

What Can We Learn from This?

Understanding Triumph of the Will is a lesson in cautious appreciation and critical viewing. It teaches us:

- Film can be technically brilliant and morally repellent at the same time.

- Innovation in art often builds on previous work, even in propaganda.

- Visual and narrative tools are powerful—they shape perception far beyond mere entertainment.

- Cinematic techniques don’t exist in a vacuum; their context and message matter deeply.

So, is Triumph genuinely innovative? Yes, in its meticulous blending of cinematic styles and its intentional crafting of narrative and image. But is celebrating it without caution a risk? Absolutely. Its innovation shines through as a mechanism crafted not merely to document but to convince and manipulate.

In the end, Triumph of the Will serves as a powerful reminder that filmmaking is never just about the image on the screen. It’s about who wields the camera, why, and how those images shape history and memory. Wouldn’t you agree that every film buff needs to see this work—if only to understand how art and propaganda can be disturbingly intertwined?

What’s your take? Can we separate art from ideology, or is that too optimistic? Feel free to dive in below!