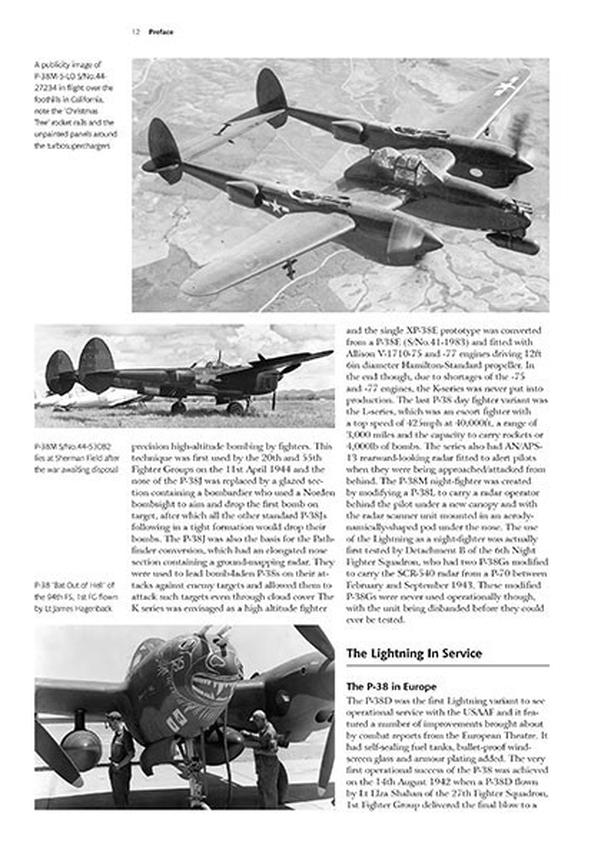

The P-38 Lightning was an effective and versatile fighter aircraft, with its performance and suitability largely depending on the theater of operation and mission role.

The P-38 excelled particularly in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Its twin-engine design offered significant advantages in performance and survivability across the vast distances of the Pacific. The aircraft’s long range and speed allowed it to escort bombers and engage enemy fighters effectively. It had more air-to-air kills than any other Allied fighter in the Pacific, credited largely to its powerful nose-mounted armament, which enabled precise shooting without the complications of wing gun convergence.

Famous American aces, including Richard Bong—the highest scoring U.S. ace—favored the P-38. It played a crucial role in high-profile missions, such as the interception and shooting down of Admiral Yamamoto’s plane, demonstrating its operational impact. The concentrated firepower from the nose-mounted guns made the P-38 an excellent platform both for dogfighting and ground attack strafing missions.

While highly effective in the Pacific, the P-38 faced challenges in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) and the Mediterranean. It struggled in high-altitude combat, where many dogfights took place over Western Europe. Early versions of the P-38 showed performance issues at these altitudes. Compared to single-engine Luftwaffe fighters like the Bf 109 and Fw 190, the P-38 had a slower roll rate and less maneuverability, common limitations for twin-engine designs. This affected its competitiveness as a pure air-to-air fighter in Europe.

Additional difficulties stemmed from tactical factors and pilot experience. In the Mediterranean and Europe, American pilots often faced veteran German adversaries with superior tactical awareness. The P-38 was introduced before Allied air superiority was established, and bomber escort tactics then limited opportunities to leverage the P-38’s strengths. Inexperience and tactical shortcomings complicated its use in high-intensity air combat compared to later Allied fighters like the P-51 Mustang.

The P-38 also proved valuable as a fighter-bomber. Its twin engines allowed it to carry a heavier bomb load than typical single-engine fighters. This enabled effective ground attacks, including strafing runs, while two engines improved survivability when facing anti-aircraft fire. This versatility made the P-38 a multi-role platform capable of adjusting to various mission demands.

The aircraft’s design conferred several operational benefits:

- Centralized Firepower: The nose-mounted guns eliminated the need for wing gun convergence, improving accuracy at longer distances.

- Performance: Twin engines enhanced climb rate and top speed, allowing rapid ascent to combat altitudes and high-speed interception.

- Survivability: Two engines reduced risks from engine failure or damage and increased mission return odds.

- Range: Large internal fuel capacity enabled extended missions, ideal for escort and interceptor duties over long distances.

The P-38 earned respect from both American pilots and adversaries. Many top American aces preferred it for its combination of speed, firepower, and versatility. Even German pilots praised its capabilities despite encountering it in combat. Nevertheless, shifting combat conditions and emerging technologies eventually surpassed the P-38’s design advantages.

The design of the P-38 was somewhat unique, with only limited replication during the war, such as in the P-61 Black Widow night fighter. However, the emergence of jet engines by the war’s end made piston-driven fighters, including the P-38, largely obsolete. Its twin-engine propeller layout did not continue into the jet age, as newer designs prioritized different performance metrics.

| Aspect | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Pacific Theater | Excellent range, speed, firepower; high kill count; effective in missions like Yamamoto interception | Few |

| European Theater | Good speed and armament | Poor high-altitude performance; less maneuverable than single-engine fighters; affected by pilot experience and tactics |

| Design Features | Nose guns for precision; twin engines for survivability; long range; heavy bomb loads possible | Complexity and size reduced maneuverability compared to single-engine fighters |

| Legacy | Respected by pilots; paved way for some designs like P-61 | Obsolete with jet technology emergence |

- The P-38 was a versatile and effective fighter, especially in the Pacific.

- Twin engines provided range, power, and survivability advantages.

- Faced challenges at high altitudes and against more maneuverable fighters in Europe.

- Effective as a fighter-bomber with a heavy payload.

- Design was influential but did not persist into the jet age.

Was the P-38 Lightning Any Good? A Deep Dive Into a Warbird Legend

Was the P-38 Lightning any good? Absolutely, but with some intriguing caveats. This aircraft was no one-trick pony; it dazzled in certain theaters and stumbled in others. Let’s unpack this warbird’s strengths, weaknesses, and why it became a legend.

Why Everyone Loved the P-38 (Mostly)

At first glance, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning seems like a superhero in WWII aviation. It came equipped with twin engines, giving it muscle and reliability.

These twin engines meant not only speed but also safety. If one engine failed or got damaged, the plane often kept flying. Pilots loved that reassurance—it literally could mean the difference between life and death.

Plus, it could carry a hefty payload of bombs and bullets concentrated at the nose. Unlike fighters with guns spread across their wings (looking at you, P-51 Mustang), the P-38’s centerline armament meant gunners and pilots didn’t have to worry about bullet convergence or spread. The pilot’s aim was the bullet’s aim. Precision? Check.

High-altitude quick climbs and long-range capabilities rounded out its skill set. This was a plane ready for the long haul—literally. Its fuel capacity allowed it to escort bombers or hunt enemy planes far from base. If the war had a marathon, the P-38 was the dependable pacer.

The Pacific Theater: P-38’s Playground

The P-38 was a star in the Pacific. Vast distances and island-hopping missions fit its design like a glove.

This plane racked up more air-to-air kills than any other Allied fighter in the Pacific. Imagine a tankier, faster, more heavily armed fighter gliding through tropical skies and getting the job done. That was the P-38.

Its armament layout made it doubly good for strafing enemy ground positions and shooting down fighters. A lethal combo!

Pilots like Richard Bong, America’s top ace, swore by the Lightning. In fact, the P-38 was behind one of the most famous missions of the war: intercepting Japanese Admiral Yamamoto. Talk about being in the right place at the right time with the right machine.

So, Why the Mixed Reviews in Europe?

Europe’s war zones weren’t the P-38’s best crowd. The high-altitude dogfights over Western Europe exposed some limitations.

Early P-38 models struggled at those altitudes. They couldn’t match the performance of German fighters in some key ways.

Most notably, the plane’s roll rate—its ability to spin quickly and outmaneuver opponents—lagged behind the fabulous BF-109 and FW-190 single-engine fighters. Bear in mind, twin-engine planes often sacrifice some agility for power and durability. The P-38 wasn’t magically exempt from physics.

So, in these theaters, it wasn’t the star dogfighter many hoped for.

Tactical Hiccups and Pilot Learning Curves

The P-38’s shortcomings weren’t always about hardware. Sometimes, the problem was the playbook.

American pilots in Europe initially were green—throwing inexperienced flyers against Luftwaffe veterans was a rough start. Many missions relied heavily on old-school bomber escort tactics that boxed P-38 pilots into roles that didn’t leverage their aircraft’s strengths.

The Lightning needed to stretch its legs, and some early tactical approaches clipped them short.

Now, About Being a Fighter Bomber

The P-38 proved itself as a fighter bomber too. Its twin engines allowed it to haul a surprising bomb load for a fighter, while the nose-mounted guns made strafing runs highly effective against ground targets.

Two engines meant getting shot at was less of a death sentence. Survivability increased, making it a wise choice for dangerous missions where flak and ground fire were risks.

Why No Copycat Design?

The P-38’s unique twin-boom design was eye-catching, but Lockheed didn’t create a batch of clones.

The P-61 Black Widow, a night fighter, somewhat mirrored its twin-engine concept, but by war’s end, jets were stealing the limelight.

The Lightning and other props swiftly became viewed as stepping stones to jet age fighters.

What Did the Pilots Say?

Many of America’s top aces picked the P-38. It’s a big endorsement when those whose lives depend on their machine consistently choose it for battle.

German aces, too, couldn’t deny respecting the Lightning. They noted its speed, firepower, and surprisingly agile maneuverability for a twin-engine plane. Respect from your enemy is real praise.

So, Was the P-38 Lightning Really Good?

Yes, but with a puzzle of nuance. It shone brightly in the Pacific, less so in Europe. The design brought survivability, speed, range, and firepower that few could match.

Its limitations were partly because of design trade-offs and partly because it was sometimes used incorrectly or too early, before pilots fully mastered its potential.

It wasn’t a perfect fit everywhere but was highly effective where it mattered most for the USAAF.

What if the P-38 had been paired with different tactics sooner or built with some aerodynamic tweaks? It might have rewritten ETO air battle history.

The moral: The P-38 Lightning earned its name as a formidable warbird capable of turning the tide when used wisely, embodying a unique chapter in aviation history.

In the end, the P-38 was more than good—it was iconic, versatile, and a beacon of tactical evolution during WWII.