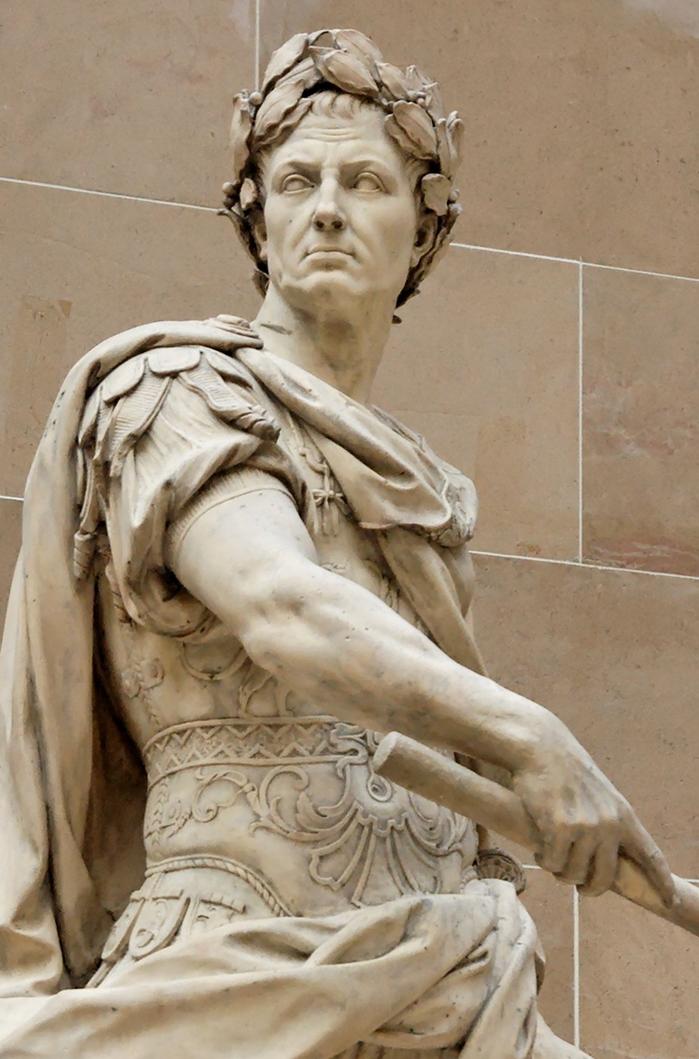

Julius Caesar was not an emperor in the formal sense recognized in Roman history, despite holding the title imperator and wielding extraordinary power over the Roman state by 44 BCE. The term “emperor” derives from the Latin “imperator,” originally a military title signifying command authority (imperium). During Caesar’s time, “imperator” was an honorific for victorious generals, not a formal state office or hereditary position.

Caesar’s political ascent began as praetor in 63 BCE and governor of Hispania Ulterior, where he possessed imperium. He earned a military triumph and relinquished imperium to pursue the consulship. As consul starting in 59 BCE, he again held imperium and later gained extended proconsular imperium in Gaul via the First Triumvirate with Pompey and Crassus. This military and political authority culminated in a civil war against Pompey, sparked partly by Caesar’s refusal to surrender his imperium.

In 49 BCE, Caesar was appointed dictator by political allies, a role granting him significant executive power including oversight of consular elections. He repeatedly secured consulships and was granted an annual dictatorship by the Senate. Most notably, in 44 BCE, he was appointed dictator for life. Despite these powers, Caesar’s authority remained personal rather than institutionalized or hereditary.

He held traditional magistracies—consul and dictator—alongside religious office as pontifex maximus. These roles gave him extensive control, including legislative influence and the ability to adjust the Senate’s membership. Yet, the Roman Republic’s fundamental structures persisted. Other magistracies remained, even if subordinate to Caesar’s authority. His power heavily depended on auctoritas, a blend of prestige, personal influence, and public support, rather than on a formal imperial institution.

The concept of emperorship evolved with Caesar’s successor, Augustus, who combined multiple critical statuses to embody the role. Augustus held the title imperator but also assumed:

- The honorific title Augustus

- Pater patriae (father of the country), symbolizing his role as Rome’s pater familias

- Princeps senatus, making him head of the Senate

- Permanent tribunician power (tribunicia potestas), controlling legislative veto and other powers

- Personal ownership of vast wealth and provinces, notably Egypt

This “bundle” of offices and honors created a lasting, institutionalized emperorship that Julius Caesar never fully attained.

Caesar, though dictator for life and pontifex maximus, never held permanent tribunician power, the hereditary princeps senatus position, nor the distinct honors of Augustus and pater patriae. His imperator title was military and temporary. These missing elements differentiate his autocracy from the later imperial office. Caesar’s rule resembled a powerful president-for-life combined with supreme religious authority, but without the multiple institutional roles securing formal emperorship.

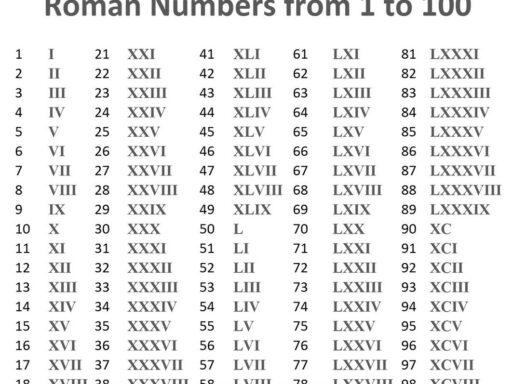

| Feature | Julius Caesar | Augustus |

|---|---|---|

| Imperator (Military Commander) | Yes, honorific | Yes, formal and regular |

| Dictator for Life | Yes | No (title abolished) |

| Princeps Senatus (Senate Leader) | No | Yes |

| Tribunicia Potestas (Tribune Power) | No | Yes, permanent |

| Honorific Titles (Augustus, Pater Patriae) | No | Yes |

| Ownership of provinces (e.g., Egypt) | No | Yes |

The distinction matters because while Caesar centralizes power, he does not create a new system replacing the Republic. Augustus crafts a new model, maintaining a semblance of republican forms but concentrating power permanently. This evolution marks the official start of the Roman Empire.

The modern label “emperor” applies posthumously and retrospectively to figures like Augustus. Julius Caesar’s power was immense, and in some ways, he was a prototype for imperial rule. However, he lacked many key attributes defining emperorship—the accumulation of multiple offices and honors created by Augustus. Historical and political realities distinguish Caesar as a revolutionary dictator rather than an emperor.

Key Takeaways:

- “Imperator” was originally a military title, not a formal emperor role in Caesar’s era.

- Caesar held extraordinary powers—dictator for life, consul multiple times, pontifex maximus—but never established a permanent imperial office.

- Augustus combined imperator with other permanent offices and honors to establish formal emperorship.

- Caesar’s power rested on personal auctoritas and temporary magistracies, not on a new institutional system.

- Julius Caesar never held the permanent tribunician power or princeps senatus titles essential to later emperors.

- Thus, Julius Caesar is best seen as a dictator and autocrat, not the first Roman emperor.

Was Julius Caesar Really Not an Emperor? Unpacking History’s Most Famous Misconception

So, was Julius Caesar really not an emperor? The quick answer: he wasn’t an emperor in the way we think of emperors today, despite holding vast power.

How can that be? After all, Caesar was the supreme figure in Rome. He reigned with almost unchecked authority by the end of his life. Yet, history and scholars draw a clear line: Caesar was never the emperor. Let’s dive into the reasons behind this distinction, and how Caesar’s complex status sets the stage for the real emperor, Augustus.

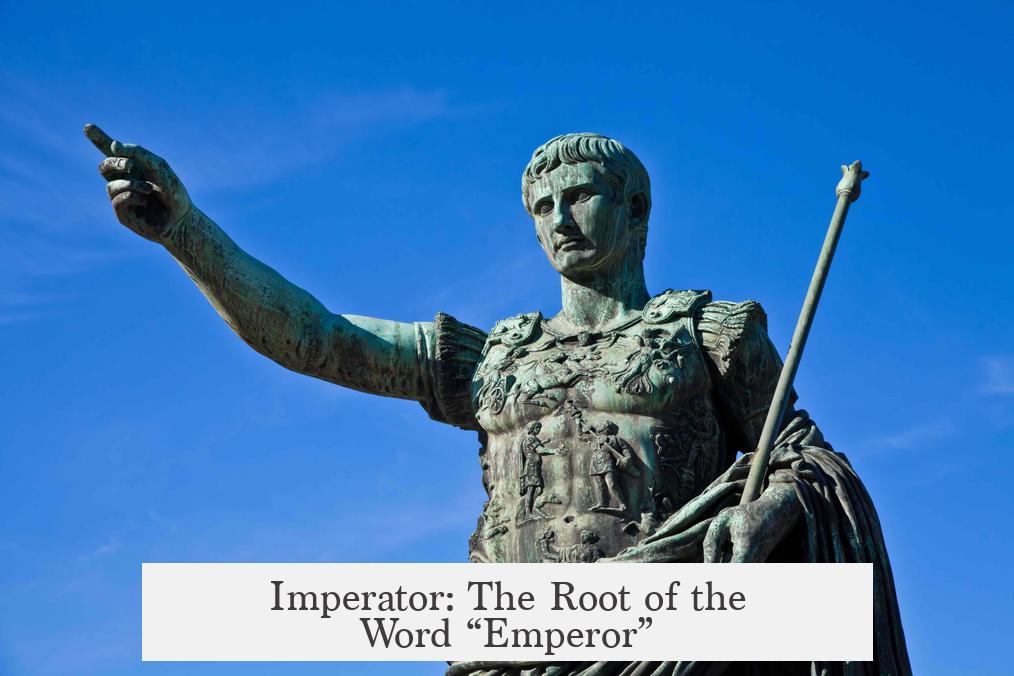

Imperator: The Root of the Word “Emperor”

It all starts with the term “emperor” itself, which comes from the Latin word imperator. Now, this word meant something a little different back in Caesar’s time.

- The original role of an imperator was a magistrate with imperium—the legal authority to command an army or govern a province.

- By Julius Caesar’s era, “imperator” was more honorific than official, generally bestowed on victorious generals by their troops before a triumphal parade.

- Caesar was certainly an imperator, especially during his military campaigns and civil war. Still, it was not a description of a permanent sovereign ruler, like what “emperor” suggests today.

To put it simply, being an imperator was awesome military bragging rights, but it wasn’t the same as holding an emperor’s crown in a formal and institutional way.

Julius Caesar’s Incredible Political Career—and His Powers

Caesar’s political climb was anything but ordinary:

- He was praetor in 63 BCE and then became governor of Hispania Ulterior, wielding imperium there.

- He earned a triumph in Spain, but had to give up his military authority to run for consul.

- He first became consul in 59 BCE, regaining imperium.

- Later, the famous First Triumvirate with Pompey and Crassus gave Caesar control over Gaul for ten years—a rare and immense power.

After conquering Gaul, Caesar refused to step down from his military commands, sparking civil war. In 49 BCE, he was appointed dictator—initially a temporary crisis role, then renewed repeatedly, and eventually granted for life in 44 BCE.

Holding imperium as consul and dictator gave Caesar enormous power. He even controlled the senate’s membership and declared war. Yet, his dictatorship—and even his lifetime rule—remained extraordinary personal powers, not institutionalized roles that passed to heirs.

Caesar’s Personal Authority vs. The Roman Republic

Despite his dominance, Caesar didn’t dismantle the Republic, which continued to function in form if not in full spirit. Magistrates were still elected, consuls still held office, though invariably under his control.

Much of Caesar’s influence came from his immense auctoritas—his personal prestige and reputation within Roman society. Think of auctoritas as social and political clout that doesn’t neatly appear in laws but controls what happens.

So, was he emperor? By then, he controlled everything, but the Republic’s institutions remained formally in place. There was no official emperor role yet.

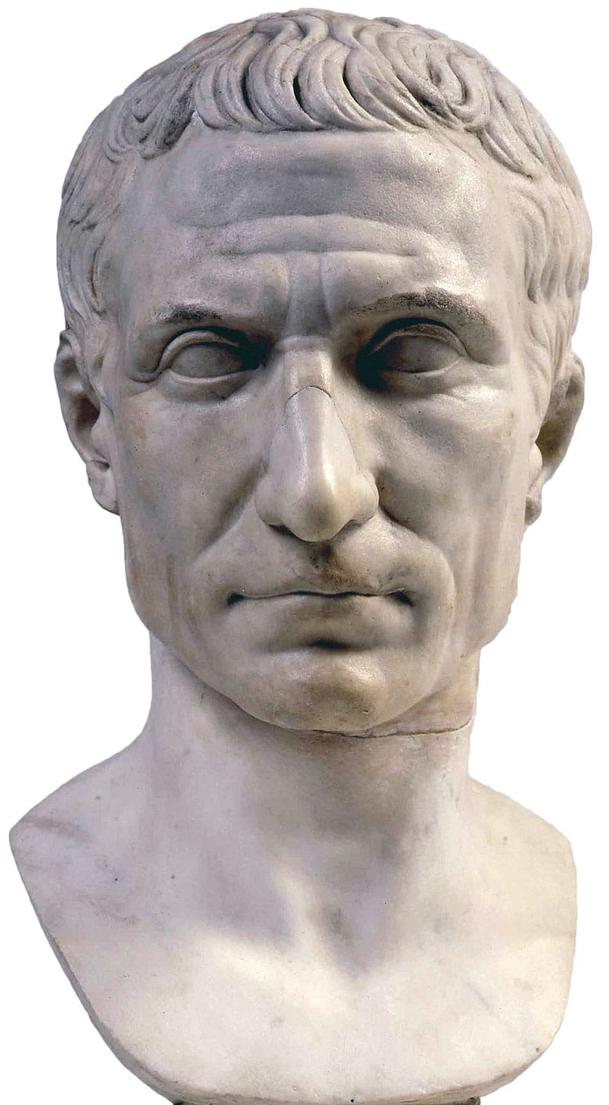

What Made Augustus The First Actual Emperor?

To understand why Caesar wasn’t emperor, look closely at what being “emperor” really meant—especially in Augustus’s reign.

Augustus bundled together multiple symbolic and powerful roles that made the emperor a unique position:

- Commander of Rome’s armies (with the title imperator).

- The honorific title Augustus, meaning “the revered one.”

- The title pater patriae (“father of the country”), which symbolized his role as the empire’s patriarch.

- Princeps senatus, head of the Senate.

- Personal ownership of large parts of the empire’s wealth and land, especially Egypt.

- Permanent tribunician power (tribunicia potestas), which gave him veto and legislative authority not tied to an annual magistracy.

Unlike Caesar, Augustus combined these roles permanently and institutionally. He was not just the strongest man in Rome. He became a political system unto himself.

Which Positions Did Julius Caesar Miss Out On?

Caesar held many important titles, but there are several critical ones he never acquired:

- He was not the permanent princeps senatus (head of the Senate).

- He was not a lifelong tribune with tribunicia potestas.

- Despite being dictator for life, those powers didn’t institutionalize into hereditary rule or a new state structure.

So, Caesar was the ultimate military leader and dictator—but that was it. Augustus added the rest, formalizing the bundle of power we recognize as “emperor.”

Modern Analogy: Power Without Permanent Institutions

Imagine Caesar as a “president-for-life” who was also the pope—highly powerful, with a foot in politics and religious authority. Very impressive!

Now imagine Augustus as a “president-for-life” who is also the majority leader of Congress, Speaker of the House, Chief Justice, and Secretary of the Treasury, all in one. That’s what made Augustus special—and the actual start of emperorship.

Caesar’s rule was transitional. It weakened the Republic but didn’t finalize a new system. Augustus wrapped up the changes and established a new era.

Why Does This Distinction Matter?

Why worry about whether Caesar was “really” an emperor? Because it shapes how we understand the shift from Republic to Empire.

Calling Caesar an emperor blurs the nuance of a massive political transformation in Roman history. His rule was a bridge—laying grounds for imperial power but not defining it.

Recognizing the real first emperor as Augustus helps us appreciate the institutional genius that kept Rome’s empire running for centuries. Augustus’s skill in combining titles and roles created the facade of a republic while wielding autocratic power.

What Can We Learn From Julius Caesar’s Career?

- Power comes in many forms: legal authority, military command, and social prestige all mix in complex ways.

- Holding an office doesn’t always equal institutional change. Caesar’s dictatorship was personal, not systemic.

- To change a political system, you need more than force—you need institutions to legitimize new roles.

So next time someone asks if Julius Caesar was really an emperor, now you can answer: he was powerful beyond belief but did not hold emperor’s office or status. That crown belongs to Augustus—who turned power into a system.

Want to Dig Deeper?

History buffs might explore how titles like imperator evolved and why Augustus’s clever layering of roles succeeded where Caesar’s did not.

Or consider the irony: Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE aimed to save the Republic but hastened the rise of the Empire he never fully became.

History has a funny way of making victors the true founders—and in Rome, that was Augustus, not Julius.

“Caesar was indisputably a titan of power, but the title of ’emperor’—with all its trappings—was a carefully crafted illusion perfected by Augustus.”