Not every single Japanese American was sent to the internment camps during World War II. Approximately 120,000 out of around 287,000 Japanese Americans on the U.S. mainland were forcibly relocated to internment camps. This constitutes about 95% of the mainland population of Japanese descent. Meanwhile, most Japanese Americans in Hawai’i—about 160,000 people—were not interned, with fewer than 2,000 detained in a single camp.

The differential treatment between mainland and Hawai’i Japanese Americans results from several factors. On the mainland, Executive Order 9066 targeted those living in military zones along the West Coast. Many could not relocate voluntarily, leading to mass forced relocation. In contrast, Hawai’i’s Japanese American community was critical to the local agricultural economy. The territory was under martial law with Lt. General Delos Emmons as military governor, who prioritized essential war efforts over mass internment. The logistical challenge of moving 160,000 people from Hawai’i to the mainland also played a part.

Some Japanese Americans on the mainland avoided internment through various means. A number joined the armed forces, with most conscripted from within the camps. Certain individuals, especially those with financial resources, relocated temporarily beyond military zones but sometimes faced expanded zones later. Others challenged the order through the courts; many ended up jailed rather than interned. Some escaped detection by going underground or off the grid.

Education offered another path away from internment for some. Japanese-American college students sometimes transferred to inland schools like Earlham College, University of Chicago, and Oberlin College. These transfers allowed them to continue studies with less interruption and avoid relocation orders.

| Population | Number |

|---|---|

| Total Japanese Americans (US Mainland + Hawai’i) | ~287,000 |

| Japanese Americans in Hawai’i | ~160,000 |

| Interned on Mainland | ~120,000 |

| Interned in Hawai’i | <2,000 |

- Not all Japanese Americans were interned; mostly those on West Coast military zones were affected.

- Hawai’i’s large Japanese community was mostly exempt due to economic and logistical reasons.

- Some Japanese Americans avoided camps by military service, relocation beyond zones, legal challenges, or underground measures.

- College students could transfer to inland schools to avoid internment.

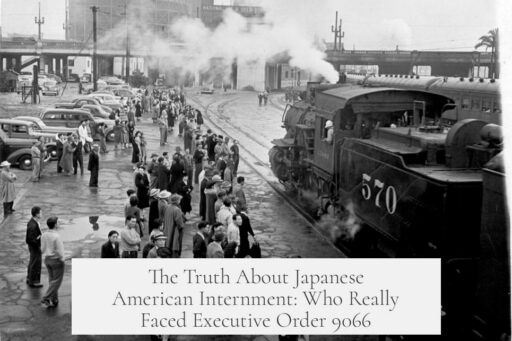

Was Every Single Japanese American Sent to the Internment Camps? The Full Story Behind Executive Order 9066

No, not every single Japanese American was sent to internment camps. This common misconception glosses over an incredibly complex and painful chapter of American history. Let’s unpack exactly who was affected by Executive Order 9066, what choices people had, and how geography and circumstance created different experiences.

You’ll be surprised to learn that while the order applied broadly to Japanese Americans in specific regions, many escaped internment due to legal, military, or practical reasons. Let’s explore the details.

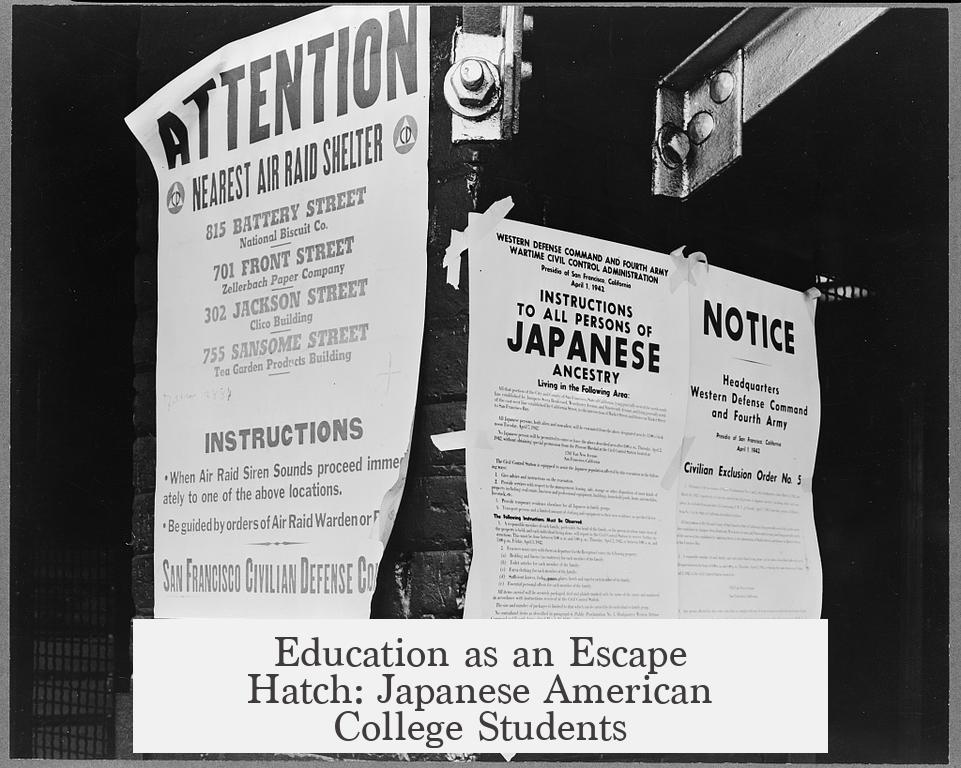

The Scope of Executive Order 9066: Who Was Actually Targeted?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1xMwUCHJdlo

Executive Order 9066, issued in 1942, authorized the military to designate certain areas—primarily on the West Coast—as exclusion zones. According to the order, all persons of Japanese ancestry in these zones had to be relocated. But here’s the catch: the order didn’t specifically say “internment camps.” Instead, it mandated that those affected could be moved to “relocation quarters,” the euphemism that led to the infamous internment camps.

At the time, approximately 287,000 people of Japanese descent lived in U.S. territories. Out of these, around 160,000 were in Hawai’i, and the majority of the rest were on the West Coast of the mainland.

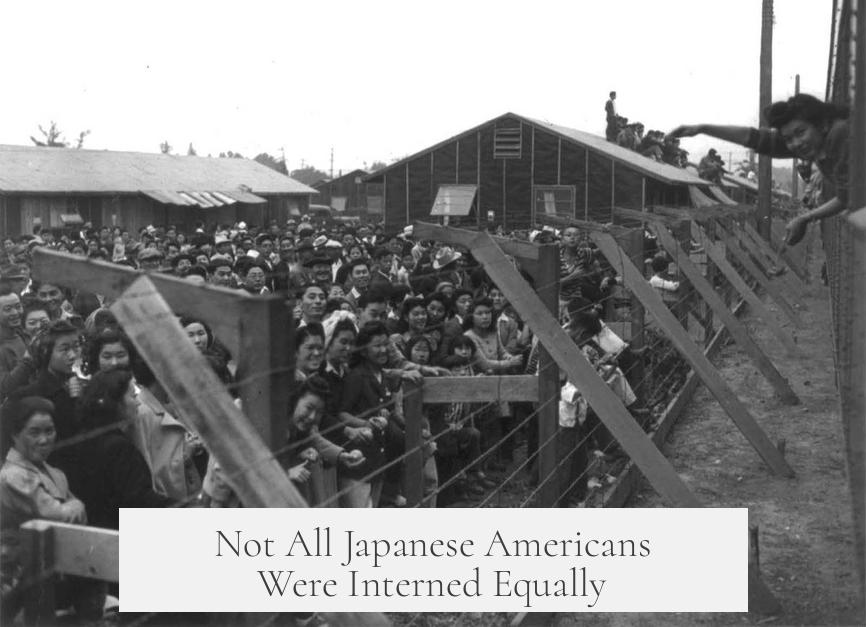

Not All Japanese Americans Were Interned Equally

About 120,000 people—around 95% of Japanese Americans on the mainland—were forced to report to these camps or were taken there by authorities. You might think that sounds like “everyone,” but what about the remaining 5%?

- Some enlisted in the U.S. Armed Forces. Interestingly, most who joined came from within the camps, but a few had military service as an alternative path.

- Others, especially those with enough resources, moved further inland, beyond the military exclusion zones. However, zones did expand later, sometimes pulling these individuals back under restrictions.

- Some fought back legally, choosing court battles that often landed them in jails, not camps.

- There were also those who simply disappeared underground, evading all attempts to relocate them.

So, while the vast majority were corralled into camps, a handful found ways to avoid internment.

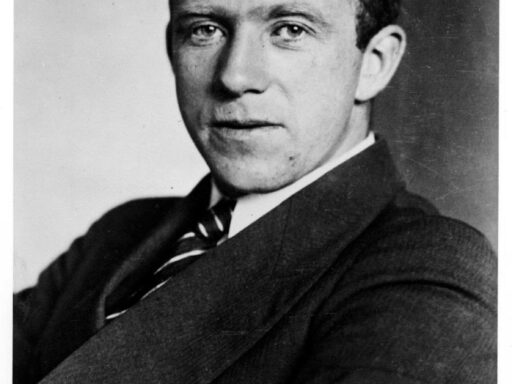

The Hawaiian Exception: Why Most Japanese Americans There Were Spared

Now, let’s talk about Hawai’i. This is where the story takes an unexpected twist. Despite 160,000 Japanese Americans living there, only about 1,200 to 2,000 were interned.

Why such a stark difference? Several key reasons come into play:

- Logistics: Transporting that many people from an island to the mainland was just impractical during wartime.

- Economic necessity: Japanese Americans were vital to Hawai’i’s agricultural labor force. Removing them en masse would cripple harvests and food supplies.

- Leadership wisdom: Lt. General Delos Emmons, then military governor of Hawai’i under martial law, decided that incarcerating most Japanese Americans was a waste of precious time and resources.

Interestingly, most of the Japanese Americans in Hawai’i were farm workers, contrasting with many on the mainland who owned farms or businesses. This difference in social and economic status also influenced treatment and outcomes.

Education as an Escape Hatch: Japanese American College Students

Not all Japanese Americans resigned themselves to internment. Many college students took a unique route to avoid camps by transferring to institutions further inland. For example, Earlham College in Indiana welcomed numerous transfer students. Universities like the University of Chicago and Oberlin College also admitted Japanese-American students fleeing the exclusion zones.

This option allowed students to continue their education with minimal disruption, offering a bright spot amid the turmoil. It was a meaningful way to resist the forced relocations.

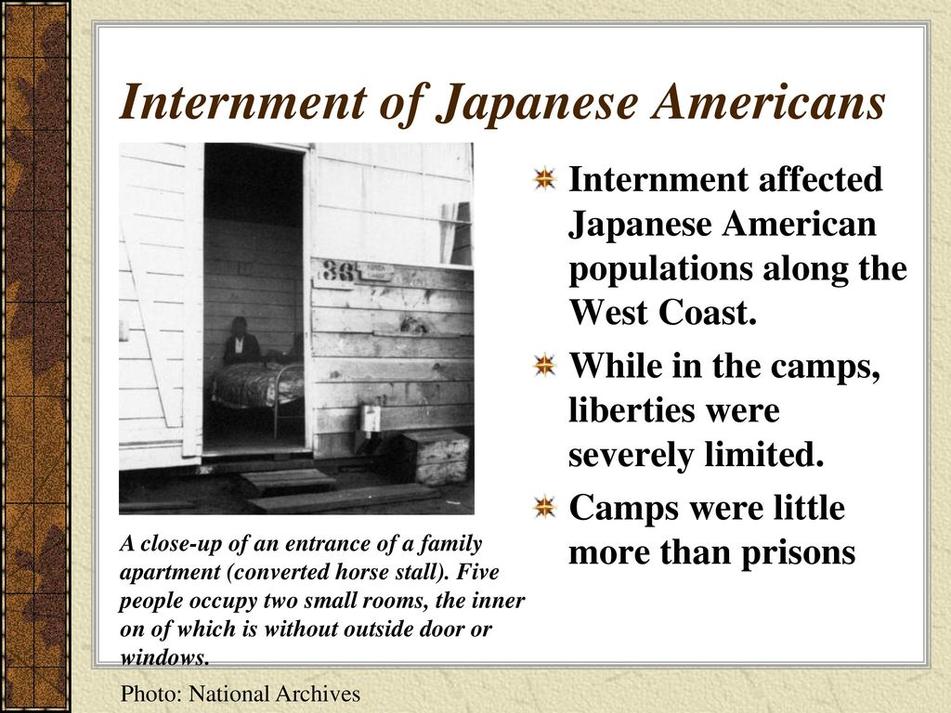

Thinking Beyond Camps: The Realities of the Internment Experience

It’s essential to remember that internment wasn’t uniform. The stories vary with geography, socio-economic status, and personal choices. Many Japanese Americans lost not just their freedom but their farms and businesses. When released, they faced financial ruin and societal stigma.

Imagine waking up one day, told to pack your entire life into a few bags, and shipped to a desolate camp under armed guard—where do you even begin to rebuild?

What Can We Learn From This?

The fact that not every Japanese American was interned doesn’t lessen the severity of the injustice. Instead, it highlights the complexity of government action, individual responses, and survival strategies during wartime hysteria.

Had you been faced with these impossible choices—join the military, flee inland, risk the courts, or go underground—what would you have done? The diversity of responses shows resilience and determination under harsh conditions.

Summary: The Complete Picture

| Category | Numbers / Facts | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Total Japanese Americans in U.S. Territory (1942) | ~287,000 | 160,000 in Hawai’i, the rest mainly West Coast |

| Forcibly Relocated to Camps on Mainland | ~120,000 (95%) | Most unable to move on their own |

| Interned in Hawai’i | < 2,000 | Limited due to labor needs and military decisions |

| Escaped or Avoided Internment By: | Remaining 5% | Armed service, moving inland, legal battles, going underground |

| Japanese American College Students | Some transferred inland | Allowed to continue education, avoided camps |

We can’t talk about Japanese American internment without recognizing these nuances. Executive Order 9066 was sweeping but didn’t mean a one-size-fits-all fate.

Understanding these specifics prevents oversimplification and pays respect to those who lived through this dark period. History may seem black and white, but it’s often painted in shades of gray—and every story is worthy of telling.