The spice trade brought high profits mainly to merchants and middlemen far from the plantations, while the actual growers and harvesters of spices gained modest, steady incomes rather than great wealth. Harvesters usually worked long hours in demanding conditions, receiving pay reflective of local standards but rarely close to the vast sums earned by traders in European or Middle Eastern markets.

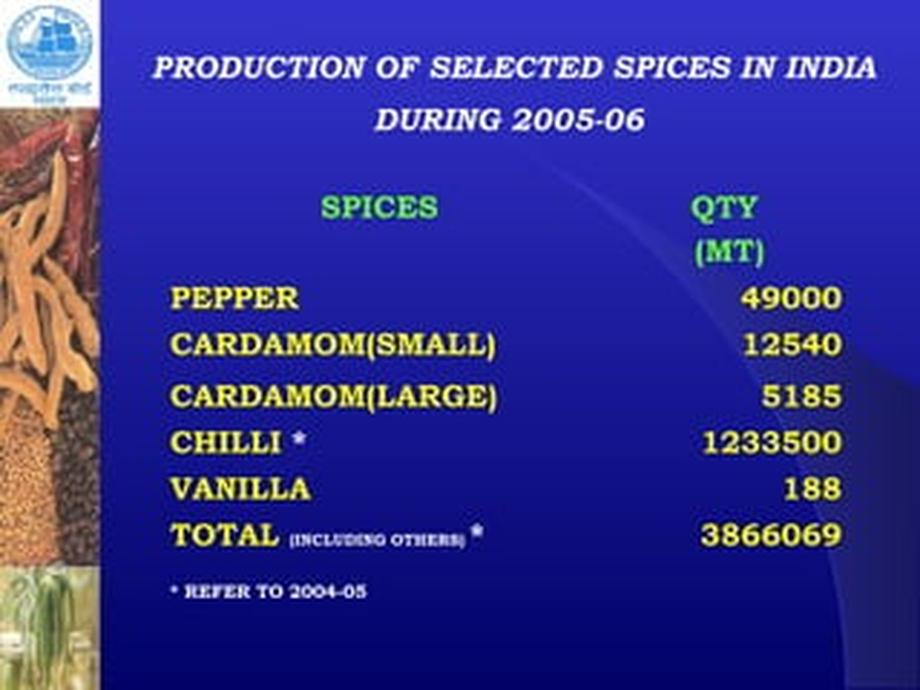

Spice cultivation often occurred in tropical regions like the Moluccas (Maluku Islands) and Indonesia. These areas produced sought-after spices such as nutmeg, mace, pepper, cardamom, and saffron. Though these spices commanded high prices abroad, their local market values remained moderate. Laborers who harvested the crops typically earned wages consistent with subsistence living rather than luxury. This economic reality reflects a longstanding historical pattern where intensive, low-status agricultural labor generates essential goods but limited individual wealth.

Plantation owners or those controlling the initial processing stages could accumulate some wealth. They managed land, labor, and early product refinement, which presented opportunities for profit beyond simple wage labor. However, the traders located near or at the end of extensive supply chains captured the majority of profit margins. These merchants controlled shipping, marketing, and distribution to demanding overseas consumers, allowing them to charge premiums that far exceeded the initial cost of raw spices.

The spice trade’s structure elevates those with market access and exclusive control, typically excluding harvesters from significant gains. Regions growing prized spices did gain collective wealth and influence. The Moluccas, for example, formed a wealthier society because of its exclusive product. Community leaders there tightly regulated prices and trade conditions to leverage their monopoly on nutmeg and mace. They maintained strict controls so the local economy could benefit meaningfully from their valuable exports.

Nonetheless, wealth disparities within these communities were significant. While leaders and merchants profited greatly, a poor social stratum persisted. Ordinary farmers and harvesters rarely accumulated enough wealth to rise much beyond modest means.

| Role | Profit Level | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Harvesters | Low to Moderate | Local wages; labor-intensive work; limited market access |

| Plantation Owners | Moderate | Land control; early processing; price control within region |

| Merchants (End of Trade Route) | High | Market control; transportation; marketing; trade monopolies |

Some exceptions exist. Rare or highly valued aromatic plants such as silphium in Roman times gave harvesters potential for better earnings, somewhat like modern truffle hunters. The gathering of frankincense and myrrh—used medicinally and spiritually rather than as food additives—often gained higher returns for collectors, owing to rarity and demand in Mediterranean cultures.

The economics of spices resemble those of essential oils. Both depend on quality and scarcity. Regions that maintained a monopoly could sustain wealth for centuries, but the actual laborers rarely became rich despite their crop’s high value overseas.

In the Moluccas, prior to European colonization, leaders understood their monopoly’s value and controlled supply. They even agreed to burn nutmeg stockpiles to maintain price stability. Yet, most locals lived on imports purchased with spice sales revenue rather than personal fortunes from harvesting.

- Harvesters generally earned low to moderate incomes despite spice trade profitability.

- Plantation owners enjoyed more wealth through land and initial processing control.

- Merchants and traders at trade route endpoints captured the largest profits.

- Regions growing spices gained collective wealth but uneven social distribution persisted.

- Rare aromatic plants and resins could yield better profits for gatherers under special conditions.

The Spice Trade Was Very Profitable for Traders. How Profitable Was It for the People Actually Growing the Spices?

Here’s the spicy truth: while spice traders minted coins by the bushel, the actual growers—the folks sweating under tropical suns—rarely saw fortunes. Their pay was steady but modest, more “daily wage” than “jackpot.” The spice trade’s juicy profits mostly seasoned the merchants’ pockets rather than those harvesting pepper or nutmeg.

Imagine working tirelessly plucking precious spices that command premium prices in distant lands, only to receive a modest income yourself. Sound unfair? That’s history for you.

Why the Bitter Taste for Spice Growers?

The profitability gap between growers and traders boils down largely to the structure of the trade chain. Spice farming demands backbreaking labor in places like Malacca or Indonesia, where the climate is ideal. Workers endure intense heat harvesting crops like pepper, cardamom, and nutmeg—the big players in the spice game. However, these spices weren’t exactly luxury items locally. In fact, in those regions, spices were often affordable, placing a natural ceiling on how much harvesters could earn.

Despite spices being precious in Europe or the Mediterranean, the local market value for labor was subdued. The tiny chunk of the profit pie going to the pickers is a reminder that manual labor seldom bottles the riches it helps create.

Who Gets the Fat Profits Then?

Plantation owners and those who started turning raw plants into spices usually accumulated some wealth. Yet, the real fat cats were the merchants at the far end of the spice routes. Owning transport, securing customer demand, and monopolizing supply chains—these parts of the trade were where profits rose sky-high.

Control was key. Regions that had exclusive rights to certain spices or aromatic oils, which were in demand for centuries, became wealthy. But the wealth trickled down mostly to those managing trade and sales rather than the pickers.

Exceptions That Spice Up the Story

There are rare exceptions to the typical tale. Take silphium, a now-extinct spice popular in ancient Rome. Its rarity made harvesting it profitable enough to resemble the lucrative lives of modern truffle hunters. Similarly, harvesting frankincense and myrrh—used as remedies rather than kitchen seasonings—followed economics akin to spice trading and offered decent pay to gatherers.

Those who collected these aromatic gums had a niche but more lucrative role in trade compared to ordinary spice pickers.

The Moluccas: Monopoly Masters but Not Everyone is Rich

The Moluccas, often dubbed the “Spice Islands,” tell a complex story. Before colonization, it appears their society was wealthy due to nutmeg and mace production. However, wealth was unevenly distributed. Community leaders held fortune and power, while many laborers lived modestly. This reveals a socio-economic divide familiar in many crop-based economies.

Interestingly, the local leaders knew the true worth of their spices. They organized governance to set prices and protect their monopoly. For instance, in the 16th century, the sale of mace was tightly controlled to maintain its value—sometimes even burning surplus nutmeg to prevent price drops.

That’s an early example of savvy brand and inventory management! Still, this control mostly benefited leaders and traders, not the average harvester.

Why Didn’t Growers Become Rich?

- Harvesting requires hard physical effort, often under harsh conditions.

- Local markets price spices cheaply, reflecting supply abundance, which restricts wages for laborers.

- Profit margins grow along the chain, peaking at trade and distribution, not production.

- Growers rarely have control over the spice’s final market or pricing mechanisms.

In essence, spice growing was profitable enough to provide steady incomes but not windfalls. The growers enjoyed a livelihood, often stable, but without the extravagant gains enjoyed by merchants or landowners.

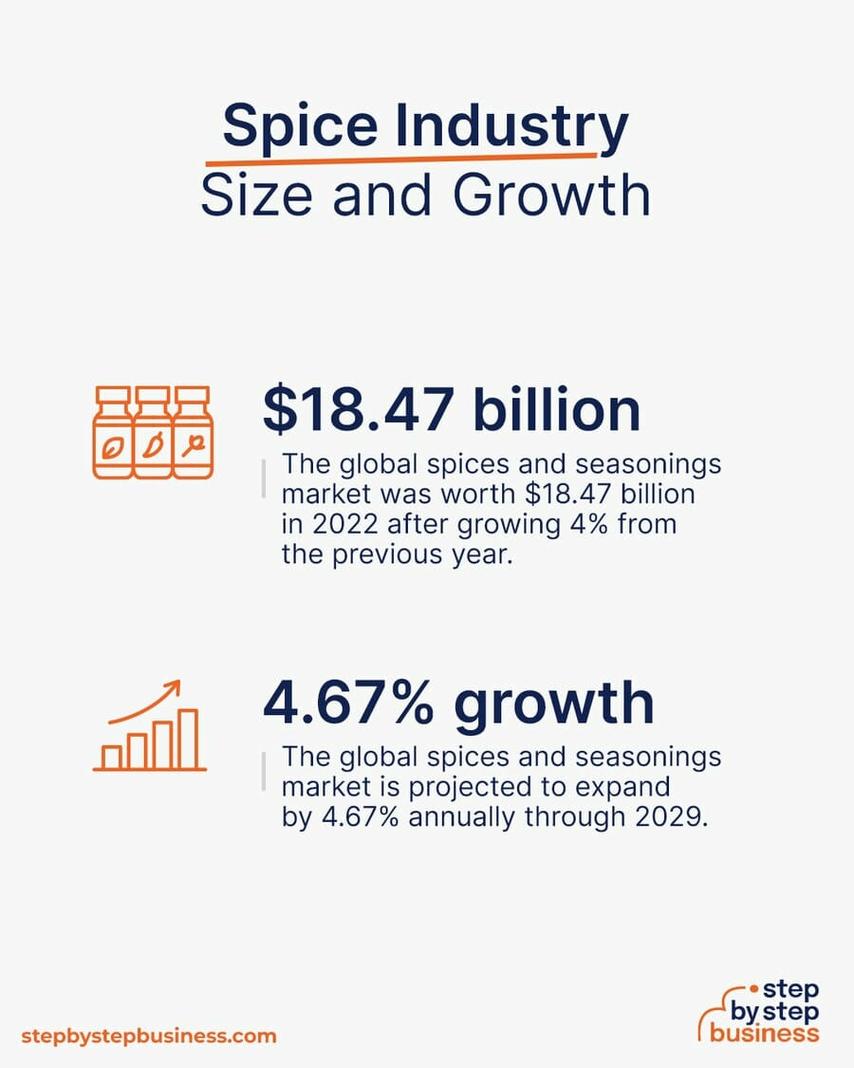

Can Growers Get a Better Deal Today?

Todays’ fair trade movements aim to alter this historical imbalance. By ensuring growers get a fair price directly, and cutting out middlemen, some producers now earn more. Still, the old dynamic lingers, making small-scale growers’ prosperity an ongoing challenge.

Wouldn’t it be sweeter for those who plant and harvest spices to savor more of the profits? The modern spice trade invites us to rethink how value is shared along the journey from farm to table.

“The spice trade shows that being at the end of the chain is deliciously profitable—but the real spice lies in equitable trade.”

Wrapping Up The Flavorful Facts

So, did spice harvesters strike it rich? Usually no. They earned a respectable living but most riches hovered near the final stages—the merchants who packaged, shipped, and sold spices abroad. The growers owned the sweat but not the secret recipe for wealth. While regions like the Moluccas enjoyed collective wealth, individual pickers were less fortunate.

Understanding this sheds light on historic global trade inequalities and fuels current fair trade ideas. Next time you sprinkle cinnamon or pepper, spare a thought for those whose hands brought that flavor to life. Their role was vital but far from a goldmine.