The mystery of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island is largely solved: the English settlers did not vanish but integrated with the Croatoan tribe on Hatteras Island. Decades of multidisciplinary research and archaeological findings support this conclusion. The colonists sought refuge and blended their lives with the Croatoans, a native group who had befriended them before the English disappeared from Roanoke in the late 16th century.

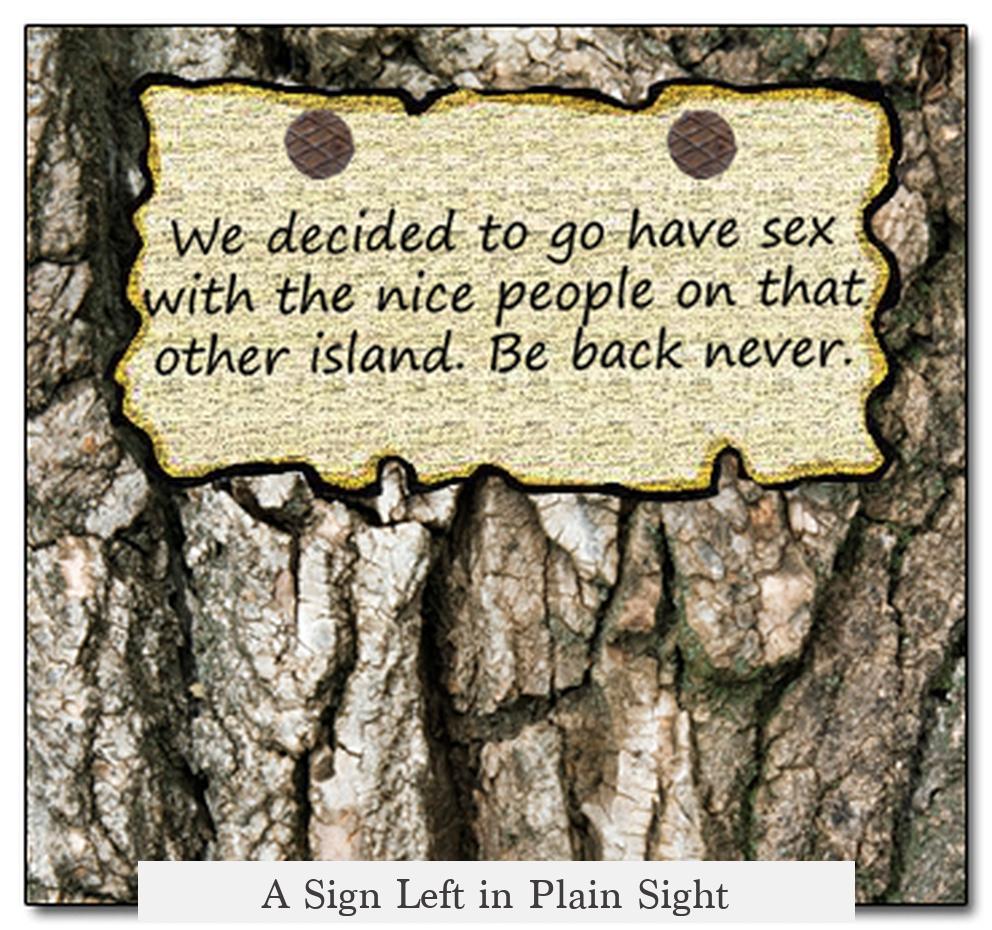

When John White returned to Roanoke Island in 1590 after a three-year absence, he found the settlement deserted. The only sign left by the colonists was the word “CROATOAN” carved into a post and “cro” etched on a tree. There were no distress signals, implying the move was planned and peaceful. White’s positive reaction to the marking, reported in his writings, indicates he believed the settlers relocated deliberately to join their Croatoan allies.

Researcher David G. Dawson, author of The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island, leads extensive efforts to understand this history. Since 2010, archaeologists, historians, botanists, and geologists have conducted digs near Buxton and Frisco on Hatteras Island. This team, including experts like Mark Horton from the University of Bristol and Henry Wright from the University of Michigan, has uncovered thousands of artifacts revealing a blend of English and Croatoan life.

Among these finds, weapons parts such as sword fragments and firearm components appear in the same soil layers as Indian pottery and arrowheads. This co-location indicates close coexistence and cultural exchange. Adaptations of English items into native uses are evident, with examples like English earrings turned into fishhooks and gun barrels repurposed as tar-tapping tools. Such creativity illustrates the merging of technologies and customs.

- A distinctive flower-shaped clothing clasp, likely belonging to one of the 16 women who accompanied the 1587 colonists, was retrieved from the site.

- Both round and square post holes were discovered, marking the presence of native longhouses as well as English-style buildings, suggesting shared or overlapping habitation.

- Animal bones from turtles, wildfowl, deer, and pigs reflect long-term dietary habits consistent with both indigenous and English diets.

- A lead tablet and pencil, possibly belonging to John White himself, provide personal and cultural links to the lost settlers. An image on the tablet depicting an Englishman shooting a native hints at the turbulent relations of the time.

Historical and cultural context deepens understanding of this integration. The Croatoans and Secotans, two notable tribes in the area, had a hostile relationship; the Secotans had enslaved Croatoans shortly before English arrival, and the English themselves had attacked a Secotan village in 1585. Amid this rivalry, the Croatoans welcomed the English as powerful allies equipped with firearms and armor.

One colonist’s death at the hands of Secotans heightened tensions. George Howe’s killing reinforced the bond between Croatoans and English settlers. It was the Croatoans who ultimately rescued the colonists by relocating them to their village on Hatteras Island. This migration is directly supported by both the carved signage and the archaeological record.

Additionally, oral histories recorded over a century later describe native individuals with blue eyes who could “speak out of a book,” a phrase likely referencing literacy introduced by English settlers. Such accounts support the notion of intermarriage and cultural blending over subsequent generations.

Primary source materials analyzed by Dawson, including writings by John White and Thomas Harriot and compilations by historian Richard Hakluyt, chronicle the early colony’s experiences and alliances. Records from Jamestown also offer insight into the local tribes’ political structures, which shaped these colonial interactions.

| Aspect | Evidence/Detail |

|---|---|

| Sign Left at Roanoke | “CROATOAN” carved on a post, “cro” on a tree, no distress marks found |

| Archaeological Finds | Swords, guns, Indian pottery, arrowheads, flower-shaped clasp, varied post holes |

| Cultural Adaptations | English earrings made into fishhooks, gun barrels into tar-tapping tubes |

| Oral Histories | Descriptions of natives with blue eyes and literacy-like knowledge |

| Historical Records | John White’s letters, Thomas Harriot’s accounts, English historian Hakluyt’s compilations |

This evidence collectively moves the mystery from speculation towards credible explanation. The Lost Colony did not disappear into oblivion but adapted and survived through integration with the Croatoans.

Key takeaways:

- The Roanoke colonists moved deliberately to live with the Croatoans at Hatteras Island, as indicated by carved signs and lack of distress marks.

- Archaeological evidence shows English and Croatoan artifacts coexisting in the same strata, confirming integration.

- Oral accounts and physical relics suggest intermarriage and cultural blending, including literacy and technology sharing.

- Historical records reflect the complex relationships among the English, Croatoans, and rival Secotans.

- Interdisciplinary research led by experts from multiple institutions underpins these conclusions, offering a comprehensive understanding of this chapter in early American history.

‘The mystery is over’: Researchers say they know what happened to ‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke Island

The Lost Colony of Roanoke didn’t vanish into thin air — it blended in. The English settlers who mysteriously disappeared didn’t get abducted by aliens or swallowed by the sea. Instead, they integrated with their native friends, the Croatoans of Hatteras Island. Yep, history’s cold case finally has a warm lead.

For centuries, the fate of the Roanoke colonists baffled historians and adventurers alike. In 1587, over a hundred English settlers, including 16 women and families, landed on Roanoke Island. When their leader, John White, returned from a supply trip to England after three long years, the village was empty, save for the cryptic word “CROATOAN” carved into a post. This eerie clue sparked wild theories. But new research paints a more realistic and fascinating picture.

Colonists Living Among the Croatoans: The Evidence

Excavations led by archaeologists and historians have uncovered some surprising proof. For over a decade, teams have dug on Hatteras Island, finding artifacts buried 4 to 6 feet underground that reveal a blend of English and Native American life. Imagine finding bits of swords and gun parts alongside Indian pottery and arrowheads, all mingled in the same soil layer. It looks like the settlers and the Croatoans didn’t just mix — they merged lifestyles.

Adaptation was key. Archaeologists discovered how the two groups borrowed tools from each other. English earrings were re-fashioned into fishhooks, and gun barrels were turned into sharp tubes for tapping tar from trees. Resourceful neighbors, indeed.

A particularly notable find was a flower-shaped clothing clasp belonging to a woman — a rare artifact that shines a light on the 16 English women who arrived in 1587. Longhouse post holes next to square English post holes confirm the coexistence of two architectural styles in harmony.

A Sign Left in Plain Sight

Back in 1590, when John White finally returned, he found “CROATOAN” carved into a post and the partial word “cro” on a tree. Crucially, no distress marks appeared, so there was no sign they fled in panic or were attacked suddenly. White himself felt hope when he saw the carving, interpreting it as a “token of their being at Croatoan,” the home of Manteo — a Croatoan chief who befriended the English. This supports the idea the colonists had planned to join their native allies.

It’s almost like putting up a note saying, “Moved in with friends, be back at Thanksgiving.” Better than leaving nothing at all.

Voices from the Past: Oral Histories

Oddly enough, some of the best clues come from native oral histories. Over a century after the colony’s disappearance, explorer John Lawson found natives with unusual traits — including blue eyes, a rarity in the region. These individuals told Lawson their ancestors “could speak out of a book,” implying that the English descendants lived among them. This anecdote strongly suggests that integration wasn’t just physical but cultural too.

The Political Context: Friends, Foes, and Survival

Understanding the strained politics of the time is essential. The Croatoans and Secotans were fierce enemies, with the latter enslaving Croatoans only years prior. The English sided with the Croatoans, who were their powerful allies, armed with guns and armor. The settlers even fought Secotans — and when George Howe, a colonist, was killed by Secotan attacks, the Croatoans stepped in to protect their friends.

So, after days of pressure and threats, the colonists found refuge in the Croatoan village on Hatteras Island. The Croatoans likely saved the settlers by moving them away from Roanoke Island’s dangers.

Behind the Scenes: The Interdisciplinary Hunt for Truth

This discovery wouldn’t be possible without a diverse group of experts. Archaeologists, anthropologists, botanists, and geologists teamed up in digs on Buxton and Frisco, small plots on Hatteras Island, for over 11 years. Leading the project, Mark Horton from the University of Bristol and Henry Wright from the University of Michigan brought expertise in anthropology and native history to the table.

Dawson and his wife Maggie even formed the Croatoan Archaeological Society to support and organize the efforts. The finds are extensive: turtle, wildfowl, and deer bones hint at a hearty diet; pig teeth appear in layers spanning generations, implying livestock integration; and curiosities like a lead tablet and pencil could trace back to John White himself — the tablet featuring a grim engraving of an Englishman shooting a native in the back, highlighting the era’s conflicts.

Turning the Page: Dawson’s Landmark Book

These revelations are elegantly compiled in David A. Dawson’s new book, The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island, released in June. It weaves original writings from John White, Thomas Harriot, and other 16th-century chroniclers, many of which were collected by English historian Richard Hakluyt. Dawson also dug into Jamestown’s records to understand the intricate political landscape of the tribes.

This book does more than fill a gap in history; it shifts the narrative from one of disappearance to adaptation and survival. It celebrates cultural blending at a time when survival demanded flexible alliances and mutual respect.

Why Does This Matter Today?

You might wonder: why should we care about these dusty dig sites and carvings on trees from four hundred years ago? Because this story offers a powerful lesson on coexistence and resilience. It reminds us that cultures can blend, adapt, and thrive despite difficult beginnings and hardships. Plus, it’s a mystery solved not by fantasy but by diligent science and collaboration.

Next time you hear about the Lost Colony, remember: they didn’t disappear. They joined their neighbors, adapted, and left a legacy hidden in plain sight — etched in soil, bones, and the DNA of generations.

So, what do you think? Could modern communities benefit from this mix-and-match approach to survival and culture? History says, definitely yes.