The letter “J” did not exist as a distinct character in English spelling until around 1633, well after Shakespeare’s death in 1616. However, the name “Juliet” as we know it today corresponds to the character Shakespeare wrote, despite the spelling differences of his time. Juliet’s “real” name in Shakespeare’s era would have been spelled with an initial “I,” such as “Iuliet,” but her pronunciation was effectively the same as the modern “Juliet.” This reflects a difference between historical written conventions and spoken language.

Before 1633, English did not officially differentiate the letter “J” from the letter “I” in print. Early English texts, including Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623), used “I” where modern readers expect “J.” For example, the title reads THE TRAGEDIE OF ROMEO AND IVLET. The letter “J” emerged from medieval scribal practices, initially as a stylistic variant of “I.” It only became recognized as a separate letter in the early 17th century. The first significant grammar text to separate “I” and “J” in English was Charles Butler’s The English Grammar in 1633.

Despite this, the sound of “J” in spoken English existed before the letter’s formal adoption. The character “Juliet” was pronounced largely the same way Shakespeare intended, close to today’s /ˈdʒuːliət/. This was because spelling conventions lagged behind spoken language changes. The name “Juliet” originates from the Italian “Giulietta,” which Shakespeare adapted. “Iuliet” was simply the Renaissance-era English way of writing the same sound. Performers in Shakespeare’s time, including potentially Shakespeare himself, pronounced the name using the “J” sound, even if the letter was not yet distinguished in print.

In early modern English manuscripts, the letters I and J represented a range of sounds and were often interchangeable. The letter “J” evolved from the Latin alphabet, which did not include it. In Romance languages, the Italian writer Gian Giorgio Trissino distinguished I and J as different letters in 1524, but English only followed this trend later. The King James Bible of 1611, predating the widespread use of “J,” uses “Iesus” rather than “Jesus.” A revised 1629 edition began incorporating the letter “J,” illustrating the transition period. This example shows how “J” was introduced gradually into English spelling through important texts and formal documents.

Other features of contemporary spelling illustrate similar delays in reflecting spoken pronunciation. For instance, in the First Folio, words have “u” and “v” usage opposite from modern conventions: “v” appears at the start of words where “u” appears today (e.g., “vp” for “up”). These were accepted written conventions rather than indications of pronunciation differences.

Juliet’s name was therefore written in several ways during and shortly after Shakespeare’s life:

- Iuliet – Common spellings using the letter “I” for the initial consonant sound.

- Juliet – Found in later prints after the adoption of “J” as a distinct letter.

Actors pronouncing Juliet’s name around 1600 would have used a “J” sound consistent with modern pronunciation. Dialectal differences might have slightly changed the exact quality of the sound, but the initial consonant was closer to today’s “J” than a plain “I” vowel sound. Shakespeare’s plays were primarily performed, not read, encouraging pronunciation continuity despite spelling variations.

The shift from “I” to “J” in writing reflected a broader linguistic evolution rather than a sudden invention. Grammar texts like Butler’s describe ongoing changes rather than invent new sounds. The “J” sound, as in “Juliet,” already existed but lacked a dedicated letter until the 17th century formalized its use. This illustrates how orthography sometimes lags behind phonetics.

The following table summarizes key points:

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Letter “J” in English | Did not become distinct until c.1633; seen as variant of “I” before then |

| Shakespeare’s spelling | Used “Iuliet” or “I” for “J” sounds in First Folio (1623) |

| Pronunciation | “Juliet” sounded like modern pronunciation despite spelling |

| Origin of Juliet | From Italian “Giulietta,” adapted by Shakespeare |

| Written conventions | Letters “u” and “v” used differently; shifts in spelling were gradual |

| Key historical documents | King James Bible 1611 (“Iesus”); revised 1629 with “J” |

In summary, Juliet’s “real” name in Shakespeare’s time would have been spelled with an initial “I,” reflecting the orthographic norms of early 17th-century English. Her actual name’s pronunciation would not differ from what contemporary audiences recognize as “Juliet.”

- “J” was initially a stylistic variant of “I” and not distinct until 1633.

- Shakespeare wrote “Juliet” as “Iuliet” but it sounded like modern “Juliet.”

- The “J” sound predated the letter and was known in spoken English.

- Written English spelling formalized “J” after Shakespeare’s death.

- Pronunciation—and performance—shaped the character’s name more than letterform.

The Letter “J” Didn’t Exist in English Until 1633. Shakespeare Died in 1616. What Was Juliet’s Real Name?

So, let’s clear the stage for this linguistic drama—Juliet’s “real” name wasn’t spelled with a J during Shakespeare’s time because that letter simply didn’t exist in English yet. Shakespeare passed away in 1616. The letter J only began to emerge as a distinct character decades later, around 1633, thanks to efforts like Charles Butler’s grammar book. But does that mean Juliet was called something else? Not quite. Let’s unravel this story.

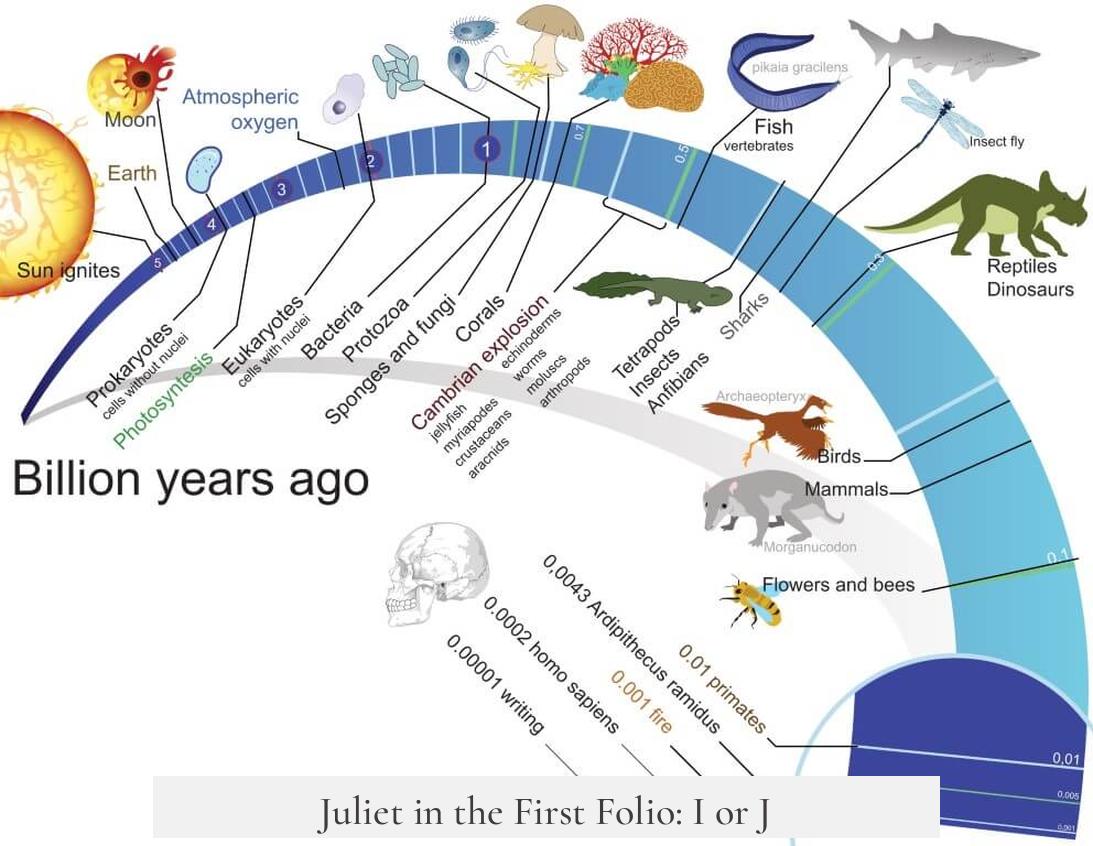

A Tale of Letters: The Birth of J in English

First things first—did the English language really lack the letter J until the 1630s? Yes and no. The sound we associate with the letter J today existed but was written differently. Before 1633, English scribes used the letter I to represent both the vowel /i/ sound and the consonantal /j/ sound, almost like a Swiss Army knife letter. The clear split between i and j is a relatively recent invention in English orthography.

Most historians credit the 1633 publication of Charles Butler’s The English Grammar, or The Institution of Letters, Syllables and Words in the English Tongue for making a formal distinction between I and J. Yet, the King James Bible’s 1629 revision was already leading the charge by distinguishing Jesus as starting with a J rather than writing Iesus as in its 1611 edition.

Even earlier, Gian Giorgio Trissino, an Italian scholar in 1524, pointed out the different sounds I and J represented in Italian, which influenced how other European languages treated these letters. The English J sound came largely from French influence and carved out its own identity quite late compared to its cousins on the continent.

Juliet in the First Folio: I or J?

Now, about Juliet herself: in Shakespeare’s First Folio, published posthumously in 1623, her name appears as IVLET (using a capital “I” for what we would now write as “J”). So the title reads “THE TRAGEDIE OF ROMEO AND IVLET.” Despite this, scholars and actors at the time would have pronounced her name pretty much as “Juliet,” very close to modern pronunciation.

This is because the written conventions of the time didn’t fully capture the evolving sounds of speech. The letter I in initial position was used in place of J, not because people said “I-u-liet” but because the letter J wasn’t yet standardized. The pronunciation wasn’t a mystery—it was always “Juliet” to the play’s audiences.

The name itself hails from the Italian “Giulietta,” which Shakespeare adapted. Italian uses the letter G to capture the “J” sound (like “juice”). English simply hadn’t caught up with writing that sound separately from I yet.

Spelling Then vs. Now: The Fluidity of English in Shakespeare’s Era

Spellings were far from fixed in Shakespeare’s day. It was common to see names and words written multiple ways, sometimes within the same document. Remember, Shakespeare didn’t hand out printed scripts to actors; his plays were performed largely from memory or scribbled notes. This oral tradition helped keep pronunciation flexible even as spelling lagged behind.

Interestingly, the same kind of letter swapping happened with other letters like U and V. Where modern readers expect a V in the middle of a word, the First Folio might use U, and at the beginning of words, a V might stand in for what we now see as U. For example, “up” could be written as “vp.” This was purely orthographic convention, not a sign of odd pronunciations.

Pronunciation Variations and Dialects: A Juliet by Any Other Name? Yes, But…

The pronunciation of the J sound has always changed by dialect. If you listened to actors in London around 1600, you’d hear something quite similar to today’s “Juliet.” But an actor from another English region might have pronounced her name a little differently.

This variation means that even if the letter “J” wasn’t on the page, the sound was alive and well in the theater. The play’s delivery was key not spelling, keeping Juliet’s name intact as far as the audience was concerned.

Why Did the J Letter Need to Appear at All?

That’s a great question! Since people were already hearing and speaking the /j/ sound, why bother creating a new letter? The answer comes down to clarity, borrowing, and printing conveniences.

- When English borrowed many words from French, Spanish, and Latin, each came with their own pronunciations and letters. Words like “hallelujah” or “Taj Mahal” keep a soft J sound not quite the same as in “Juliet.”

- Writers and printers realized that distinguishing i from j visually made texts easier to read and interpret, especially with religious texts like the Bible gaining huge importance.

So, later 17th-century printers formalized what was happening naturally in speech into writing. From then on, the stroke on the letter transformed I into J when representing consonantal sounds, cleaning up confusion.

The Practical Side: What Did This Mean for Juliet’s “Real” Name?

Shakespeare wrote Juliet as IVLET or Iuliet, depending on the spelling and manuscript, but always intending the name to sound like the modern “Juliet.” The letter J was simply unavailable or unused in England at that time to denote that initial sound.

This means that in reality, Juliet’s name was pronounced as we say it now, and Shakespeare’s audience would have heard no difference. The spelling didn’t obscure her identity; it only reflects the orthographic practices of Elizabethan England.

Personal Experience and Fun Fact

I’ve always found it fascinating how the “J” has such a rich backstory. Imagine being an English speaker in 1610, pronouncing “Iuliet” aloud with no letter J in sight. It’s like texting without emojis—effective, just lacking a bit of flair.

This evolution reminds us how flexible and living language is. Thank goodness Shakespeare’s plays survive, so we can enjoy Juliet’s story even without that fancy new letter on the page!

Summary Table: Comparing Spelling and Sound Before and After J

| Aspect | Before 1633 | After 1633 |

|---|---|---|

| Letter for /j/ sound initially | “I” (e.g., IVLET for Juliet) | “J” (Juliet as we know it) |

| Formal distinction between I and J | Not standardized; both letters combined | Officially distinct letters in English alphabet |

| Pronunciation of Juliet | Practically the same as modern pronunciation | Same pronunciation, standardized spelling |

| Examples in religious texts | “Iesus” in 1611 King James Bible | “Jesus” in 1629 revision of King James Bible |

Final Thoughts: Does the Spelling Change the Name?

In the end, the absence of the letter J in Shakespeare’s time doesn’t mean Juliet wasn’t Juliet. It means English spelling was catching up with English speech. Names and words lived in the spoken realm before their letters had a proper home on the page.

So when you read “IVLET” in the play’s First Folio, don’t get tangled up in the letters. Listen to how Romeo calls out to her on stage. That voice carried the true name—timeless, spirited, and just as romantic as today’s Juliet.

Doesn’t it make you wonder what other “missing letters” might be hiding in plain sight, shaping our history in subtle ways?