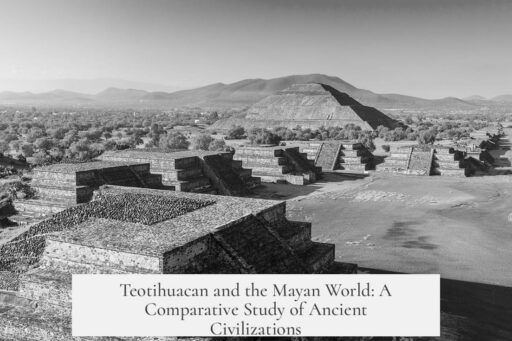

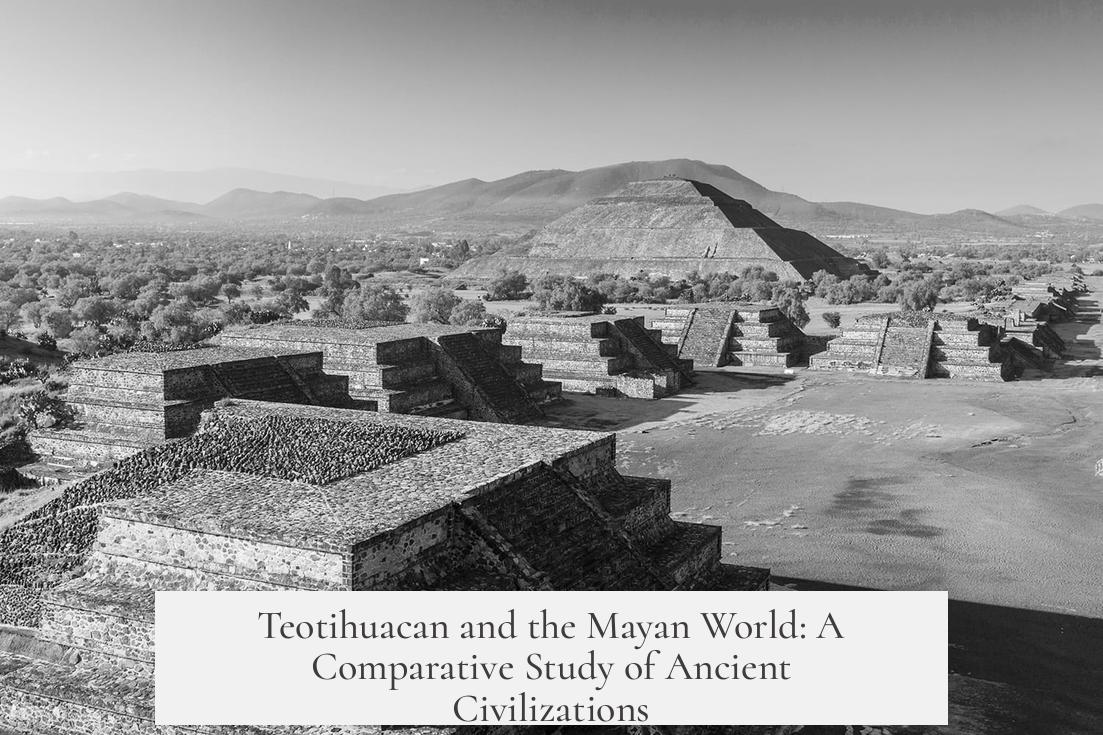

Teotihuacan and the Mayan world represent two distinct yet interconnected civilizations in ancient Mesoamerica, each with unique cultural, political, and artistic identities. Their interaction, particularly marked by the Teotihuacan entrada in 378 AD, reveals a complex relationship involving political intrigue, cultural influence, and economic exchange.

Teotihuacan, located near present-day Mexico City, was a vast metropolis and a multi-ethnic urban center estimated to have housed around 100,000 residents. The city was characterized by an orderly grid layout, low economic inequality, and impressive military might symbolized by images of warriors and human sacrifices in military regalia. Despite its significance, the exact identity and language of Teotihuacan’s rulers remain uncertain, as the city lacks depictions or the names of individual rulers. The language spoken might have been Otomí or another Mesoamerican language, but no consensus exists.

In contrast, the Maya civilization was composed of politically fragmented city-states spread across southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. These city-states, such as Tikal and Calakmul, shared religion and culture but were often in competition, with shifting alliances. The Maya area was prized for its luxury goods like jade, cacao, and quetzal feathers, which attracted interest from Teotihuacan as a far-eastern source of wealth, representing a tropical paradise.

A crucial point of contact is the arrival of Sihyaj K’ahk’ (“Fire is Born”) in Tikal in 378 CE, documented exclusively in Maya inscriptions. He likely came from Teotihuacan and marked a pivotal event known as the Teotihuacan entrada (“entry”). The day Sihyaj K’ahk’ arrived coincides with the death of Tikal’s reigning king, Chak Tok Ich’aak (“Jaguar Paw”). Sihyaj K’ahk’ was probably sent by a powerful ruler named Spearthrower Owl, who held a Central Mexican-style name referencing an atlatl, a weapon not used by the Maya. Shortly after, a new king, Yax Nuun Ayiin, identified as Spearthrower Owl’s son, was enthroned at Tikal. His portraits exhibit Teotihuacan-style headdress and geometric art, signaling strong foreign influence.

Archaeological evidence in Tikal supports this narrative. The Mundo Perdido complex, constructed around this period, incorporates the talud-tablero architectural style, a hallmark of Teotihuacan. This style, defined by sloping panels on buildings, is a distinctive cultural marker tracing Teotihuacan influence across Mesoamerica. Alongside architecture, artifacts such as the “Thin Orange” pottery style, Tlaloc effigy vessels, and green obsidian appear at Tikal and related sites like Copán and Rio Azul. These findings suggest both cultural transmission and political engagement.

However, the precise nature of Teotihuacan’s influence over the Maya remains debated. Some scholars argue for outright conquest, citing inscriptions that depict Teotihuacan’s military incursion and the installation of puppet rulers in Tikal. Others caution this may reflect palace intrigue or propaganda, suggesting local Maya elites adopted Teotihuacan symbolism opportunistically. The limited inscriptions and absence of forts or garrisons in conquered regions imply a hegemonic rather than direct control. Teotihuacan may have used indirect strategies, such as resettling artisans from the Maya lowlands in their city, creating ethnic barrios, and circulating goods to foster economic dominance.

| Aspect | Teotihuacan | Mayan World |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Central Mexican highlands | Southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras |

| Political Organization | Multi-ethnic metropolis, unclear rulers | Fragmented city-states with shifting alliances |

| Language | Unknown (possibly Otomí) | Various Mayan languages |

| Architecture | Talud-tablero, grid city | Varied Maya styles, later incorporation of talud-tablero |

| Writing System | Unknown or undeciphered | Advanced hieroglyphic system |

| Artifacts | Thin Orange pottery, Tlaloc vessels | Polychrome ceramics, jade, obsidian |

The Zapotec city of Monte Albán experienced a similar infusion of Teotihuacan influence, including the sudden appearance of talud-tablero architecture and burial customs emulating those of the central Mexican metropolis. This suggests broader regional interactions where Teotihuacan extended its economic and political reach. Trade also intensified, for example with Zapotecs exporting mica to Teotihuacan while importing thin orange pottery, illustrating a complex exchange network.

Excavations in Teotihuacan reveal a Maya presence, notably in the Plaza of the Columns. Maya residents likely lived in a compound containing murals with typical Maya imagery and colors uncommon in Teotihuacan. Early feasting ceremonies show shared Maya and Teotihuacan stylistic elements in serving ceramics, indicating peaceful social mingling. However, later deliberate destruction of Maya-style murals and possible massacres hint at deteriorating relations, possibly reflecting political tensions or conflict.

Despite this contact, reciprocal Maya influence on Teotihuacan remains minimal. The advanced Mayan writing system was apparently not adopted broadly outside Maya territory. This asymmetry highlights the distinct cultural trajectories and political dynamics between the two centers.

Yax Nuun Ayiin’s reign and his lineage underscored Teotihuacan’s impact on Maya states, especially in art and political symbolism. Yet, over generations, the Maya rulers increasingly reasserted local authority by blending foreign elements with indigenous traditions. The relationship gradually shifted from direct influence toward a distinctive Maya expression.

Key insights into Teotihuacan-Maya dynamics include:

- The Teotihuacan entrada at Tikal marked a major cultural and political turning point but is known primarily through Maya inscriptions.

- Teotihuacan’s military and economic influence extended into the Maya lowlands and beyond but lacked classic imperial direct control features such as forts or permanent garrisons.

- Architectural styles like talud-tablero and artifacts such as thin orange pottery trace Teotihuacan’s cultural footprint across Mesoamerica.

- The presence of ethnic barrios in Teotihuacan, including Maya neighborhoods, reveals imperial strategies based on resettlement and economic integration.

- Maya rulers eventually integrated Teotihuacan motifs with native culture to legitimize their authority, demonstrating cultural synthesis rather than suppression.

- Reciprocal influence from Maya to Teotihuacan remains scarce, particularly in writing and broader cultural adoption.