The idea of a “real life Camelot” centers on identifying historical places and figures that inspired the legends of King Arthur and his court. Tintagel in Cornwall is one of the most discussed sites tied to Arthurian lore, mainly for its strategic location, archaeological findings, and deep connections to regional tradition. However, genuine proof for Camelot’s existence remains elusive, complicated by how legends evolve and the reuse of Roman structures in post-Roman Britain.

Tintagel, located on the north Cornish coast, was part of the post-Roman kingdom of the Dumnovians. This kingdom controlled key trade routes along the Atlantic coast of Europe. Its access to valuable resources such as tin, gold, and copper gave it economic power lasting over a century. Such wealth could have supported a significant ruler, possibly the type of leader who inspired Arthurian tales.

Archaeology strengthens Tintagel’s Arthurian links. Excavations uncovered artifacts and an early stone etching bearing a name resembling Arthur’s. Local folklore has long associated Tintagel with Arthur’s birthplace or seat of power. Building materials found on site include stone, turf, wood, and thatch, typical of the era, suggesting a constructed settlement of some substance rather than a mere fortification.

Despite these clues, the historical truth behind legends like King Arthur is hard to pin down. The concept of Euhemerism suggests that myths often derive from real individuals, but this is difficult to confirm. Folklorists argue that oral traditions usually do not trace back to actual events. Stories tend to emerge organically rather than from specific historical incidents.

Widespread motifs, such as the “Dragon Slayer” tale exemplified by Perseus in Greek legend, appear globally with variations but rarely tie to a real person. Arthur’s legend likely began with multiple possible “proto-Arthurs” — leaders or warriors from post-Roman Britain. These figures might have inspired the later composite narrative but differ drastically from the medieval King Arthur persona.

The search for a historical Arthur often confuses seeds with trees. Early candidates may share genetic links to the legend, but they are neither the fully formed King nor the symbolic Camelot. Thus, the legendary Arthur serves more as a cultural and literary figure than a confirmed historical monarch.

Part of the legend’s endurance is the visible Roman heritage in Britain, reused in the post-Roman era. Large Roman constructions, especially the Saxon Shore forts built in the 3rd century, persisted and served new rulers. For example, Portchester Castle preserves Roman defensive walls, built under Emperor Diocletian around 285-290 AD, and later medieval halls and towers reused these walls. Such continuity in architecture reflects practical reuse and symbolized authority, possibly feeding into legendary narratives.

Hadrian’s Wall and similar Roman fortifications also saw partial reuse during the chaotic post-Roman period. This reuse signals how early medieval Britons maintained some control over remnants of Roman power. Whether these places had any direct influence on the Arthurian legend is uncertain, but their prominence would inspire stories and lend gravity to rulers who occupied or reused them.

The allure of Camelot lies in its blend of history, myth, and regional identity. Tintagel and other sites like Portchester hint at a layered past where economics, military strategy, and culture merged. Meanwhile, the legend itself warns that historical truth may not be a straightforward fact but a tapestry woven from many threads, some real and others imagined or transformed over centuries.

- Tintagel’s archaeological site and folklore link it strongly to Arthurian legends but provide no definitive proof of a historical Camelot.

- Legendary figures like King Arthur often represent a mix of several possible historical leaders rather than a single individual.

- Oral traditions and myths evolve independently of historical events, making the search for literal truth difficult.

- Roman structures, reused in post-Roman Britain, underscored continued power centers that may have inspired parts of the Arthurian narrative.

- Places like Portchester Castle show tangible examples of Roman military architecture adapted in early medieval times.

- Overall, Camelot functions more as a cultural myth than a concrete historical location.

Real Life Camelot? Unraveling the Legend and Its Roots

Is there a real-life Camelot? The short answer: maybe, but it’s complicated. We love the idea of a shining castle ruled by noble King Arthur and his knights. But peeling back the layers of history, myth, and archaeology shows a much richer and messier story.

So, where might the echoes of Camelot truly lie? And how do historians sift legends from facts when it comes to a figure as mythical as Arthur? Let’s embark on this historical quest.

Tintagel: Tintagel Is Definitely a Contender

Think of Tintagel on the north Cornish coast like a VIP player in post-Roman Britain’s power game. The kingdom of Dumnonia, covering modern Devon and Cornwall, enjoyed a prime spot for trading across Europe’s Atlantic coast.

Tintagel wasn’t just a fancy name; this area controlled valuable tin reserves, along with some gold and copper. Tin was the silicon of the ancient world—essential for making bronze. That made Tintagel an economic hotspot for over a century.

Hold on to your Excalibur! Archaeologists discovered an early stone etching near Tintagel hinting at a name eerily close to Arthur. Combine that with regional folklore, and the castle takes on a legendary glow.

- Building materials used at Tintagel? Stone, turf, wood, and thatch. These choices highlight practical local resources, not fairy-tale castles forged from magic bricks.

This mix of archaeological clues and folklore firing up imaginations makes Tintagel a tempting stand-in for Camelot. But does trading power and a name stone make it THE Camelot? We’ll see.

The Elusive Truth in Legend: Fact, Fiction, or Folklore?

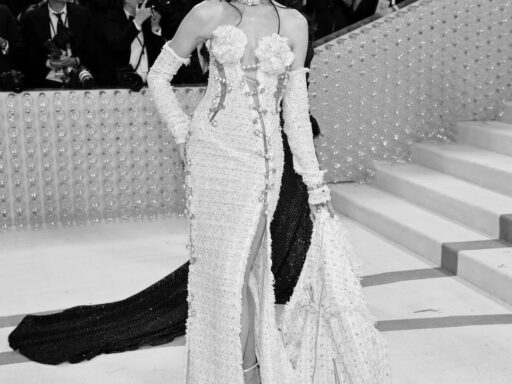

Legends like King Arthur’s sit at the crossroads where history, myth, and storytelling collide. The Greek thinker Euhemerus introduced the idea (called Euhemerism) that gods and heroes might be based on real people. It sounds promising until you recall that folk tales often float off into fantasy territory.

Folklorists warn us: chasing the “real event” behind oral tales usually leads nowhere. Stories pop up spontaneously over time, shaped not by a single incident but social, cultural or moral needs.

Take the “Dragon Slayer” folktale, cataloged as AT 300 by folklorists Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. The story of Perseus in classical Greece is an early example, yet no one claims he fought an actual dragon in history textbooks.

King Arthur? Searching his origins floods the internet with hundreds of theories. Possible “proto-Arthurs” may have existed. But none look anything like our legendary king—more like seeds than mighty oaks.

The King Arthur we know is less a historical figure and more a grand tapestry woven from many threads—some real, others spun in the fires of imagination.

Roman Legacies: Stones That Tell Stories

Post-Roman Britain didn’t start from scratch. Roman buildings stood proud—or at least partially usable—long after Rome’s legions left. Among these were the impressive Saxon Shore forts, built in the 3rd century.

Imagine a huge stone fortress, weathering centuries—this was the setting for Portchester Castle near Portsmouth harbour. Originally a strategic Roman naval base built under Emperor Diocletian, it guarded vital waterways.

The archaeology here is rich and revealing. Excavations by Barry Cunliffe uncovered traces of a tenth-century hall and tower built within the Roman walls. This blending of Roman and medieval structures hints at continuity amidst change.

Even parts of Hadrian’s Wall show signs that later inhabitants repurposed the massive Roman defenses. If the medieval Camelot existed, it could easily have been built atop or near such sturdy, historic foundations.

Bringing It All Together: The Real Life Camelot?

So, does “real life Camelot” exist? If you mean a shining castle with a round table and knightly quests exactly as legend tells, then no. But Tintagel and sites like Portchester show how history planted seeds for the Arthurian myths.

Economic hubs like Tintagel had power and influence, enough to inspire stories of kings and heroes. Roman forts lending their stone bones to medieval castles underscore continuity and importance in these places.

Here’s the twist: the legends we embrace are products of centuries of storytelling layering fact, myth, and cultural need. King Arthur is not a frozen snapshot but a living legend evolving with each retelling.

Could Tintagel have hosted a chieftain whose deeds ignited stories? Absolutely. Could Portchester’s Roman walls have witnessed early medieval leaders resembling Arthurian characters? Quite possibly.

But finding Camelot is less about hunting a specific ruin and more about understanding how human history, geography, and imagination fuse into one enchanting tale.

What Can We Learn From This?

- Archaeologists and historians provide clues, not certainties. The absence of hard proof doesn’t kill the allure.

- Legends need real-world anchors to thrive. Trade power, impressive stone works, folklore—these give the Arthurian myth its roots.

- Oral tradition crafts heroes as embodiments of cultural hopes and ideals. Trying to find an exact real person is less fruitful than appreciating the story’s role.

In the end, the pursuit of “real life Camelot” teaches us as much about medieval Britain as it does about storytelling’s magic. The blend of archaeology, history, and folklore keeps the legend alive.

Ever wonder why King Arthur still captures imaginations? Maybe it’s because Camelot isn’t a single place—it’s a powerful idea inspired by many places, including Tintagel’s rocky coast and the shadows of Roman stone walls. It’s history, mystery, and magic rolled into one.