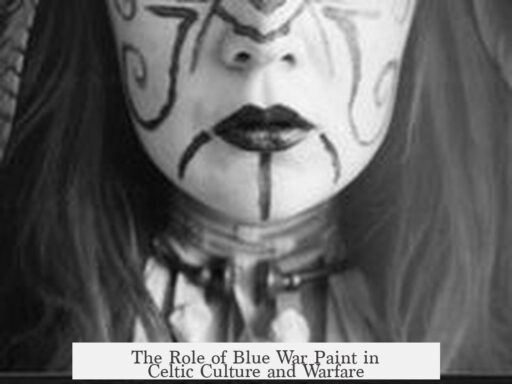

The Celts likely used blue body paint made from woad for war and ceremonial purposes, but the evidence is complex and partly debated. Ancient Britons, especially the Picts, are reported to have painted or tattooed themselves, using blue patterns possibly derived from the woad plant. However, the durability and exact nature of this blue body coloring remain uncertain.

The idea that Celts painted themselves blue is deeply rooted in history and popular culture. This belief mainly stems from ancient writers like Julius Caesar, who described Britons dyeing themselves blue with a plant-based pigment before battle. Caesar’s “Commentarii de Bello Gallico” reports, “All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue color and makes their appearance in battle more terrible.” This account anchors the image of blue war paint firmly in ancient records.

Archaeological finds support some association with woad. Seed pods identified as woad, dating about 2,000 years back, have been uncovered in Britain. Woad (Isatis tinctoria) yields a blue dye and seems to be the source of this coloring tradition. However, the practical use of woad as paint presents challenges. Woad dries rapidly, flakes off the skin, and is difficult to fix firmly, especially when soldiers sweat in combat. Additionally, its caustic nature means high concentrations could irritate or burn skin.

Ancient sources provide mixed descriptions of Celtic body decoration. Roman historian Herodian mentioned that certain Celtic tribes adorned their bodies with patterns or pictures, calling them “grafaís.” Coins from Gaul illustrate Celtic leaders with permanent or temporary tattoos. The Picts, a Celtic people, were labeled by the Romans as “Picti,” derived from Latin, meaning “painted.” This ties their identity directly to body painting or tattooing.

The exact form of body decoration—paint, tattoo, or scarification—remains debated. Tattooing was likely widespread among continental European Celts, while blue body paint from woad seems mainly linked to the British Isles and the Picts. Caesar does not mention Gallic Celts using blue paint, implying regional differences. War paint possibly functioned as temporary decoration, whereas tattoos served as permanent marks.

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Color | Blue hues from grey-blue to black-blue, produced mainly by woad; exact shade unknown due to dye limitations. |

| Material | Woad plant, possibly copper or iron-based pigments as alternatives. |

| Function | Military intimidation, tribal identity, religious ceremonies, and social status indication. |

| Patterns | Complex symbols, spirals, and interwoven designs representing protection, strength, and tribal affiliation. |

| Limitations | Woad difficult to fix on skin, potential skin irritation or burns from high concentrations. |

Woad’s functional benefits extended beyond color. The plant’s astringent properties may have aided combatants by providing mild antiseptic effects on skin. This could have helped wounds or prevented infection during battle. Still, practical use of woad paint for warfare posed challenges, forcing careful preparation or use in minimal quantities.

Modern experimentation reveals further insight into ancient techniques. Santa Barbara tattoo artist Pat Fish attempted tattooing with woad dye but found it ineffective for permanent skin marking. This suggests that if Celts used woad, it was mostly as paint rather than a lasting tattoo pigment.

The Celts’ war paint also served social and religious roles. Pliny the Elder recorded that Britons’ wives and daughters-in-law stained their bodies blue for certain rites, marching naked as part of religious ceremonies. This shows the dye’s use beyond combat contexts.

Open questions persist. Scholars wonder if patterns were entirely painted on, tattooed, or combined. The full range of motifs and their meanings remains partially speculative. It’s unclear if body paint or tattoos were common to all classes or reserved for warriors and elites. The exact source of blue pigment—woad or metals—is still debated.

The practice endured beyond the Roman conquest of Britain but faded by the 7th or 8th century AD. After that, the tradition of blue body painting diminished, likely due to cultural changes and influences.

- Celts, particularly in Britain, used blue body paint or tattoos produced mainly from woad plant dye.

- Julius Caesar and Roman historians provide primary accounts linking Celts to blue body decoration.

- Woad dye was difficult to fix on the skin and could cause irritation, limiting usage and permanency.

- Paint or tattooed symbols likely indicated tribal membership, status, and served religious or military purposes.

- Differences existed between British Celts (blue paint) and continental Celts (more tattoos).

- The tradition lasted until early medieval times but eventually disappeared.