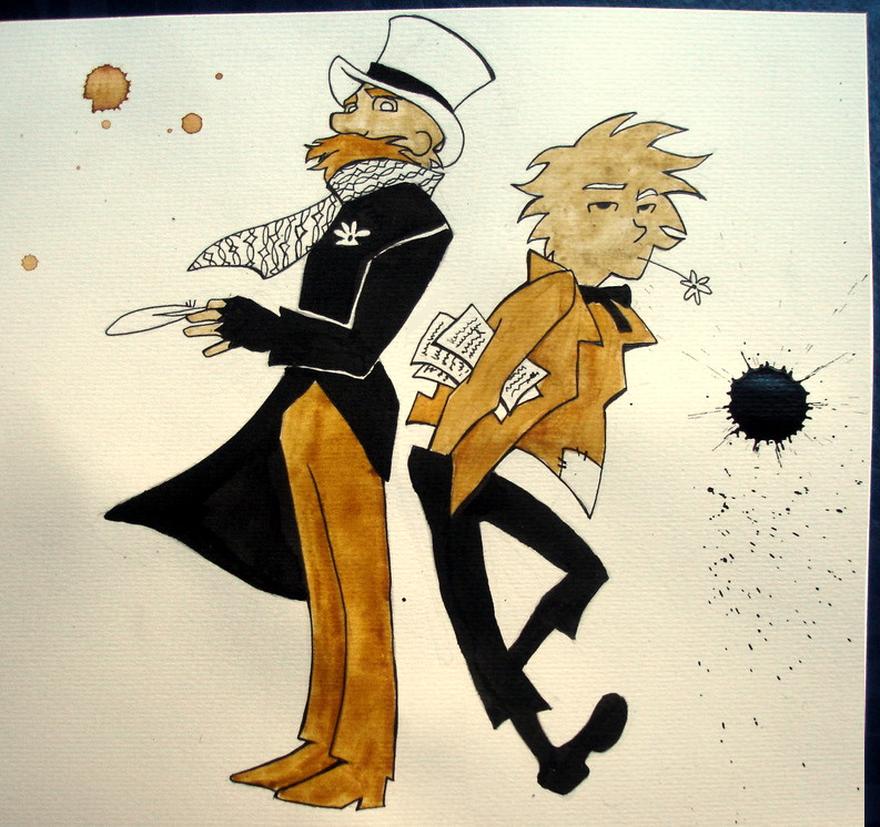

Poets Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine were not arrested in 1860s France despite being openly lovers because homosexuality had been decriminalized in France since 1791, and the legal system did not specifically punish consensual same-sex relationships. The social and legal context allowed for some degree of discretion and evasion, even amid suspicion and harassment.

France decriminalized homosexuality during the French Revolution in 1791, removing it from the list of criminal acts. This legal framework continued into the 1860s. While same-sex acts were not illegal, social attitudes remained conservative and suspicious. Police often maintained files on suspected homosexuals and used other laws to intimidate or harass individuals, but direct legal action for homosexuality as such was not an option.

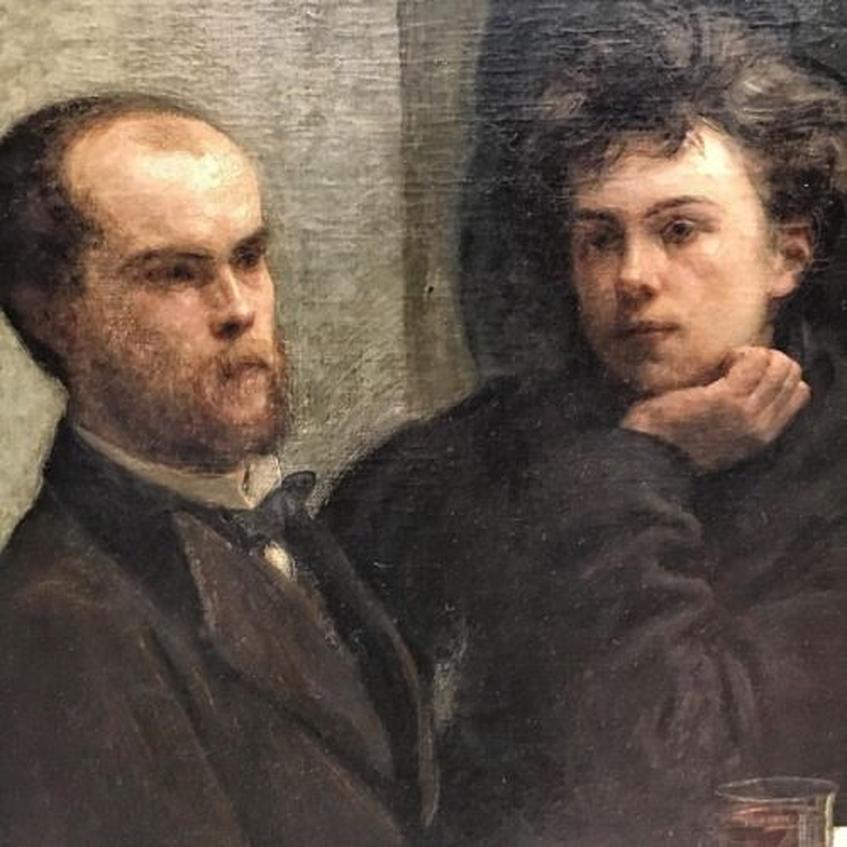

Rimbaud and Verlaine’s relationship was known within certain small literary circles in Paris but did not reach widespread public attention at the time. Rumors emerged soon after Rimbaud arrived in Paris in late 1871, but Verlaine’s correspondence reveals attempts to deny or minimize these claims. Their social circles were limited, and their public profiles modest, which contributed to their ability to avoid serious scrutiny.

Additionally, Verlaine was married and his marital issues were publicly attributed to his alcohol use and violence, not his same-sex relationship. His wife Mathilde reportedly did not fully understand or believe the nature of Verlaine’s relationship with Rimbaud until after they separated and letters were revealed.

After fleeing to London in 1872, where homosexuality was illegal and harshly punished, they experienced a different legal climate. However, before the 1885 Labouchere Amendment in England, prosecution for homosexual acts required high standards of proof, making arrests less frequent. Authorities often opted for harassment or surveillance rather than outright arrest.

Both Paris and London had emerging queer subcultures that provided some community and strategies for discreet social navigation. Within these enclaves, individuals like Rimbaud and Verlaine could express their identities with a combination of subtlety and defiance.

- Homosexuality was decriminalized in France since 1791, allowing consensual same-sex relations without direct legal penalty.

- Police harassment existed but lacked specific laws to arrest individuals solely for homosexuality.

- Rimbaud and Verlaine kept a relatively low profile; rumors were confined to literary circles.

- Verlaine’s marital troubles overshadowed suspicions about his sexual orientation publicly.

- Queer subcultures in Paris and London allowed some social navigation despite repression.

How Were Poets Arthur Rimbaud and Verlaine Not Arrested in 1860s France Despite Being Openly Known as Lovers?

In short, Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine were never arrested in 1860s France because homosexuality had been decriminalized since 1791, and their relationship, though known within small literary circles, was never officially publicized or targeted by authorities. Sounds simple, right? But the story mixes legal nuances, societal attitudes, and underground subcultures that paint a vivid portrait of their unusual, tempestuous partnership navigating 19th-century Europe.

Let’s dive into why these star-crossed poets managed to live—and write—together without the looming shadow of the law.

Homosexuality Was Not Illegal in France—A Revolutionary Legacy

Unlike many countries in the 19th century, France struck down laws criminalizing same-sex acts way back during its Revolution. In 1791, the revolutionary government decriminalized homosexuality by removing sodomy laws—part of a sweeping modernization effort on personal freedoms.

By the 1860s, this meant that while society often viewed homosexuality with suspicion or disdain, the police had no legal grounds to arrest someone simply for loving a person of the same sex. Sounds progressive for the time? Well, yes and no.

Authorities kept close files on known or suspected homosexuals. Harassment, surveillance, and social stigma were everyday realities. However, no direct arrest for homosexuality occurred because the law didn’t treat it as a criminal act. Instead, police might exploit other public order or morality laws selectively—against “scandalous behavior” or public indecency, for example—but this was shaky and inconsistent.

Rimbaud and Verlaine’s Relationship—A Secret in Plain Sight

Their love story wasn’t a headline in Parisian newspapers but whispered in literary salons and artistic circles. When Rimbaud came to Paris in September 1871, their relationship began sparking rumors quickly. A contemporary review even called Verlaine’s companion “Miss Rimbaud,” a slight mystery sprinkling a veil of ambiguity over their bond.

Nonetheless, such rumors barely escaped the small, artistic enclaves where both poets were relatively unknown. Verlaine’s letters of the time repeatedly deny these whispers—or implore friends to keep quiet—revealing their attempts to maintain a fragile privacy.

So, was their relationship “openly known?” Only among their circles, yes. But “public knowledge” is different. The wider society barely caught wind, and even when they did, it didn’t translate into legal action.

Marital Troubles Disguising the Truth

Verlaine was married to Mathilde, a woman who reported his drinking and violent behavior to be the cause of their split—not any supposed relationship with Rimbaud. In fact, Mathilde claimed she didn’t even understand what homosexuality was until after the poets left Paris and their letters surfaced.

This denial or obliviousness meant their homosexual relationship was not a factor in the public or legal battles they faced. In a society less aware or willing to discuss these matters publicly, personal issues often overshadowed hidden truths.

Flight to London—Trading French Freedom for British Constraints

When Rimbaud and Verlaine fled to London in mid-1872, they entered another legal world where homosexuality remained illegal. However, enforcement was spotty before the strict Labouchere law of 1885. Despite harsh penalties previously—ranging from death to imprisonment—the police needed strong proof, usually eyewitness testimony, to convict.

This high burden of proof, plus a police reluctance to intervene in private lives, meant many queer individuals in London could live with some discretion, much like their situation in Paris. Rimbaud and Verlaine thus managed to avoid arrests even abroad.

The Role of Emerging Queer Subcultures and Social Navigation

Both Paris and London hosted budding queer communities that provided sheltered spaces. In cafes, private salons, and underground networks, men like Rimbaud and Verlaine found a degree of connection and relative safety.

Such subcultures enabled them to live their lives with tactics of subterfuge and defiance—being discreet yet genuine in their identities and relationships. They weren’t completely “out” like modern public figures might be today, but they carved out niches where they could exist.

What Does This All Mean?

From a modern viewpoint, no arrests seem surprising. But the truth is more intricate. France’s legal framework post-Revolution gave them legal protection, but social prejudice lingered. Their semi-private lives, societal ignorance or indifference, and powerful emerging queer networks shielded them.

Verlaine’s marital problems being blamed on his personal faults rather than sexuality also deflected attention. Meanwhile, police harassment was real but had no full legal backing to make arrests for homosexuality. Finally, the nuanced difference between “openly known within circles” and publicly proclaimed was critical to their safety.

Can We Learn from Rimbaud and Verlaine’s Story?

“Their path reminds us how laws alone don’t define freedom or safety; social attitudes and networks matter, too.”

This historic example highlights a paradox: legality without acceptance offers limited protection, while community support—even secretive—can empower marginalized identities. Their artistic brilliance thrived not despite but alongside their complex social navigation.

If you wonder how far we’ve come, consider this: even today, visible LGBTQ+ identities still face challenges in many parts of the world. Rimbaud and Verlaine’s lives show the importance of legal reform paired with cultural and social progress.

In Closing

The poets Arthur Rimbaud and Verlaine lived at a remarkable crossroads of history. Their love persisted, partly because French law since 1791 did not criminalize homosexuality; partly due to the limited public scope of their relationship; and partly thanks to discreet queer networks like the ones emerging under the Parisian boulevards and London streets.

So next time you read their passionate verses, remember that behind the poetic fire was a delicate dance with a society that watched, judged, but couldn’t and didn’t quite suppress their bond.

After all, poetry itself is rebellion—and their love was too.

Was homosexuality illegal in 1860s France, and how did that affect Rimbaud and Verlaine?

Homosexuality had been decriminalized in France since 1791. It was not illegal for Rimbaud and Verlaine to be lovers. However, police monitored suspected homosexuals and sometimes harassed them using other laws.

Why were Rimbaud and Verlaine not widely exposed despite rumors about their relationship?

Their relationship was mostly known in small literary circles. Verlaine was barely famous, and Rimbaud was unknown then. Many rumors existed, but Verlaine often denied them publicly.

Did Verlaine’s marriage impact public knowledge of their relationship?

Verlaine’s marriage was troubled mainly due to his violence and drinking. His wife did not suspect homosexuality then and only learned about it later from their letters.

How did the social environment in Paris and London help Rimbaud and Verlaine avoid arrest?

Both cities had early queer subcultures allowing some social navigation. Despite repression, men like them found ways to live openly with some concealment and defiance.

What legal risks did Rimbaud and Verlaine face if arrested for their relationship?

In France, homosexuality was not illegal, so no direct risk. In London, it was illegal but required strong proof to convict. Police often avoided intervention unless forced.